Attorney general opinion says Richmond statues may be moved

Jeremy M. Lazarus | 9/1/2017, 7:46 a.m.

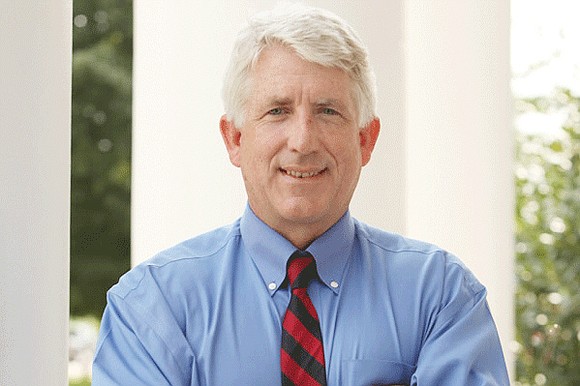

Richmond apparently could remove four of the five Confederate statues on Monument Avenue without violating a state law protecting them, according to an opinion from Virginia Attorney General Mark R. Herring.

While the state protection law has been in place since 1904, it initially only covered Civil War statues put up in counties. It was expanded 20 years ago to include statues in cities and towns.

The law cannot be applied retroactively to Confederate statues like those in Richmond and other cities that were put in place before 1997, Mr. Herring stated.

He cautioned, however, that other legal restrictions could bar removal of Confederate statues, and he stated that any community’s decision to “remove or relocate a war or veteran’s monument … would require careful analysis to determine which (factors) might limit local authority.”

Mr. Herring issued the opinion Aug. 25 to Julie Langan, director of the state Department of Historic Resources.

The opinion represents the attorney general’s official legal position, but it does not make new law and doesn’t prevent the state Supreme Court or lower courts from reaching a different conclusion.

Based on the opinion, the only Confederate statue on Richmond’s Monument Avenue with state protection is the one of Robert E. Lee. That’s because the state owns the statue that has stood at Allen and Monument avenues since 1890.

The four other statues on Monument Avenue all were erected well before the 1997 state law barring disturbance or removal of such statues was applied to cities.

Those statues are of James E.B. “Jeb” Stuart (1907), Jefferson Davis (1907), Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson (1919) and Matthew Fontaine Maury (1929).

An additional Richmond statue, one to Confederate A.P. Hill, which has stood since 1892 at the intersection of Hermitage Road and Laburnum Avenue, also could be impacted by Mr. Herring’s ruling.

Mr. Herring, without mentioning the Richmond statuary, noted in his opinion that the General Assembly began authorizing and protecting Confederate statues in 1903, but limited the specific and general laws to counties even after adding statues regarding other wars.

His analysis also found that the General Assembly failed to make the law retroactive when it updated the law in 1997 to include all localities.

“The longstanding rule in Virginia is that statutes are ‘construed prospectively only’ ” to prevent interference with “existing contracts, rights of action or lawsuits and vested rights,” Mr. Herring wrote, unless the General Assembly makes it clear that the law applies to previous situations.

“When the General Assembly omits a clear manifestation that a statutory change should apply retroactively, it generally should be concluded that the legislature did not intend such an application,” he continued.

Evidence that the protection law does not apply to pre-1997 statues in cities, he stated, can be found in a 2016 statue protection act that Gov. Terry McAuliffe vetoed.

Mr. Herring stated that the removal of statues could be impacted by other legal actions.

For example, if a locality accepted a federal or state grant to preserve a statue, that grant could require continued preservation, he stated.

Or if a locality accepted the donation of a statue, the donation contract could include a requirement for preservation, he added.

That could be the case in Richmond, where members of Richmond City Council have indicated that old contracts involving the acceptance of Confederate statues may contain clauses requiring Richmond to keep them in place forever.

“Careful investigation of the history and facts concerning a particular monument in a given locality should be completed to determine what, if any, restrictions might apply,” Mr. Herring concluded.