50-year reunion

Student civil rights workers recall efforts

Dale M. Brumfield | 6/27/2015, 12:14 a.m.

The Charleston, S.C., church shooting is an ugly reminder that “racist violence is not a ghost,” said Bruce Smith 71, of Woodbridge, a volunteer lobbyist for AARP.

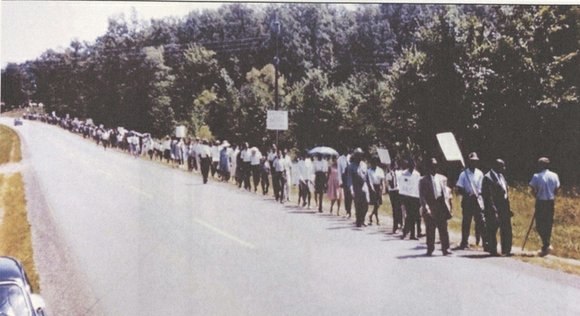

Fifty years ago, Mr. Smith, a student at Lynchburg College, was among a group of Virginia college students who went into the impoverished so-called “Black Belt” of Southside Virginia to help empower African-American residents by registering them to vote.

The Virginia Students Civil Rights Committee, formed in late 1964 under a program of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, planned to “attack the roots of the social evils of poverty, deprivation and segregation.”

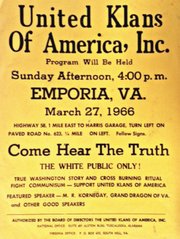

Some of their efforts were met by hatred and intimidation, including rallies by the Ku Klux Klan.

During a 50th anniversary reunion last weekend in Blackstone, alumni of the VSCRC recalled their efforts in the Virginia communities that started in the summer of 1965.

The VSCRC, a racially diverse group, didn’t go into the Deep South. Instead, they elected to travel to the rural counties of Amelia, Dinwiddie, Lunenburg, Nottoway, Powhatan and Brunswick. The median income of these counties in 1964 was $3,350. One-fourth of all African-American families earned less than $1,000 annually and nearly 70 percent of black students dropped out of school.

With only 18.6 percent of African-Americans in the area registered to vote, the VSCRC’s primary initiative was voter registration drives. Once settled in churches and family homes, the students teamed with local black leaders, such as the late Lunenburg Branch NAACP President Nathaniel Lee Hawthorne, and went door to door with the goal of upsetting a white-controlled power structure that kept many African-Americans in a cycle of poverty and second class citizenship.

The group also addressed farming inequities in an area where tobacco reigned as the cash crop. Many poor black and white farmers were forced into sharecropping because of unfair seed and fertilizer allotments.

“We had to get in the system to change it,” said Dr. Lucious “Duke” Edwards, 71, retired archivist at Virginia State University, an original chairman of the project. “We would eat breakfast on Main Street” in Victoria, he recalled. Mr. Smith or Bob Foley, who are both white, “would put sugar in their coffee, then hand me the same spoon to use — just to aggravate people.”

“They needed to be picked on,” Mr. Edwards continued, noting that the federal 1964 Public Accommodations Act outlawed racial discrimination in restaurants, but the local business owners would not follow it.

“We weren’t breaking the law by sitting at the counter,” Mr. Edwards said. “They were breaking the law.”

Still, residents of the rural communities were hesitant to rock the boat.

“I drove up a dirt road to a house and I saw the people running out the back door, frightened that some white guy was coming,” said Scott Marshall, 67, who was active in the Civil Rights Movement.

“Sharecroppers wanted nothing to do with me,” said Bill Monnie, 72, who attend Penn State University and had participated in voting rights marches in Selma, Ala., just months earlier in March 1965.

Aware of the VSCRC’s work that summer, the North Carolina KKK came into several counties and near the town of Victoria to organize rallies.

After seeing a burning cross in a yard, Nan Grogan Orrock organized a successful boycott with fellow VSCRC members against the Victoria Chamber of Commerce for not stopping a nearby rally. “We drove people to Kenbridge to shop,” she said.

Ms. Orrock, now 71, represents a heavily African-American district of Atlanta and East Point, Ga., in the Georgia Senate.

Today, the impact of the VSCRC’s work is difficult to quantify, as the area is experiencing different problems than in 1965.

The graduation rate for African-American students in the area is around 84 percent, according to Virginia Department of Education statistics. And the median income for African-American families ranges from $25,659 in Brunswick County to $46,875 in Dinwiddie County, according to 2013 figures from the U.S. Census Bureau.

While the VSCRC convinced county registrars to expand their hours, resulting in hundreds more African-Americans on the voter rolls, people today — both black and white — simply don’t vote, said retired Virginia Court of Appeals Judge Larry G. Elder of Dinwiddie, who was elected commonwealth’s attorney in Dinwiddie in the mid-1970s. He said Dinwiddie County has 11,000 registered voters but only 700 cast ballots in the June 9 primary election.

“In the 1970s, Lunenburg County was booming and blacks could get jobs,” said Shirley Robertson Lee, a historian in Victoria.

Today, the priorities seem misplaced, she said.

“Grant money is coming in, but it is creating parks and horse trails. Factories are closed. There are no jobs, but there are running trails,” she said.

Lunenburg resident Sarah Foster thinks race relations have actually regressed. “Blacks and whites don’t communicate,” she said. “I don’t see any improvement.”

There was complete agreement, however, of the role Mr. Hawthorne, the Lunenburg NAACP president, played in his dogged fight against segregation until his death in 1974.

“Hawthorne was fearless, and an effort should be made to name a school after him instead of segregationists like Mills Godwin,” Mr. Smith said, referring to the former governor.

The VSCRC “is something that stayed with me my whole life,” said Dorothy Walker Hatchett, a Victoria resident whose family housed some of the students in 1965. “I got a degree in social work because I knew it was necessary. It has been bittersweet, too, looking at what is going on, especially with what happened in Charleston.”