60 years back, 60 years ahead

5/20/2016, 10:11 p.m.

Education is the great equalizer, so it has been said.

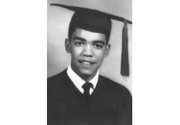

Take for example Irving L. Peddrew III.

He was a teenage honors student at his all-black high school in Hampton whose future seemed limitless. He received offers to attend numerous schools across the nation. Yet he chose Virginia Tech in Blacksburg.

That may not seem important, but for this young African-American man, it was a life-changing decision: The racial integration of the entire university fell on his back.

That was in 1953. He was the lone black student at the rural, public university with more than 3,000 students.

He was isolated and alone, unable to live on campus, eat in the cafeteria or participate in social activities like the rest of the students.

Even as three other black students joined him at Virginia Tech the following year, the burden of obtaining an education in those circumstances proved too difficult, and Mr. Peddrew left the university after three years. Two of the others also left — one after a single year and the other after three years.

Last week, Virginia Tech did the right thing. It owned up to the extraordinary burden placed on Mr. Peddrew and awarded him an honorary bachelor’s degree in electrical engineering.

He is now 80 years old.

When we talk about education and the opportunity it affords, we don’t always consider the total circumstance that often makes policy and practice two separate and distinct things. In Mr. Peddrew’s case, the policymakers finally opened the all-white Virginia Tech to an African-American student. But what he found in terms of actual practice was quite different from the support and resources given to his white counterparts.

That’s what the entire 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision by the U.S. Supreme Court was about — that the educational practice of “separate but equal” was in fact not equal — that African-American students in racially segregated public schools were not given the same resources as their white counterparts. Nor were the African-American students enrolled in schools that were integrated in name only.

Unfortunately today, more than six decades after Mr. Peddrew’s regretful experience at Virginia Tech and the Brown decision, our public schools are facing similar disparities of resources that threaten the future of our children.

A report issued Tuesday by the nonpartisan Government Accountability Office found little has changed, with deepening segregation of African-American and Latino students in high poverty K-12 public schools. These schools often offer fewer math, science and college prep classes, while having disproportionately higher rates of students who are held back in ninth grade, suspended or expelled.

“While much has changed in public education in the decades following this landmark decision and subsequent legislative action, research has shown that some of the most vexing issues affecting children and their access to educational excellence and opportunity today are inextricably linked to race and poverty,” the report said.

More than 20 million students of color attend racially and socioeconomically isolated public schools, according to Congressman Robert C. “Bobby” Scott of Newport News, the ranking Democratic on the House Committee on Education and the Workforce and one of the lawmakers who requested the study.

“This report is a national call to action,” Congressman Scott said.

While we applaud Virginia Tech for coming to terms with its hurtful actions of the past, we urge our readers to be mindful of the destruction of students occurring in the present.

Richmond Public Schools continues to wrangle over financial resources that are forcing cuts to programs and the number of teachers in classrooms. We are being made aware of growing violence and disciplinary issues that are detracting from the core educational mission and goals of our schools.

Where are we headed? Where are our children headed? Back to the past? Or toward something better?

For the parents, teachers and advocates who flooded the streets and Richmond City Hall seeking more money for schools and to avert the closure of Armstrong High School and four elementary schools, we say: Stay involved. Show up at School Board meetings. Ask questions. Investigate where resources are going and how decisions made by the School Board and the schools administration will impact the children.

Will the children graduate to a brighter future, or like Mr. Peddrew, receive an acknowledgment of “we’re sorry, we failed you” 60 years from now?