The real context behind Monument Avenue

8/4/2017, 9:55 a.m.

The Virginia Defenders for Freedom, Justice & Equality issued the following open letter to members of the Monument Avenue Commission:

As Richmonders who have long called for the removal of the Confederate statues on Richmond’s Monument Avenue, we would like to express our views on this matter as the Monument Avenue Commission begins its process of public engagement.

Our concerns focus on three issues: The limited mandate of Mayor Levar M. Stoney’s commission; the commission’s composition; and the artificial separation of the issues of memorializing Confederate figures while failing to commit to properly memorialize the history of Richmond’s Shockoe Bottom, once the epicenter of the U.S. domestic slave trade.

When Mayor Stoney established the commission, he said that taking down the monuments was not an option: “I wish these monuments had never been built. But like it or not, they are part of our history in this city and removal will never wash away that stain.”

Limiting the mission of the commission merely to providing “context” to the statues of slavery-defending figures is unacceptable. These monuments were erected to rehabilitate the image of the slavery-defending Confederacy and culturally re-establish the principle of white supremacy during the worst post-slavery period for black people in U.S. history.

The statues on Monument Avenue were only the grandest part of this nearly 100-year campaign to turn the former capital of the Confederacy into a virtual shrine to the Lost Cause mythology.

Richmond’s first Confederate memorial — to Gen. “Stonewall” Jackson — was erected in 1874 in Capitol Square, just nine years after the end of the Civil War. Reconstruction in most of the South lasted 11 years, but ended much sooner in Richmond.

It would be another 16 years before the towering statue of Gen. Robert E. Lee would be unveiled on what would become Monument Avenue. Others followed in rapid succession: Gen. William Carter Wickham in Monroe Park (1891); Gen. A.P. Hill at Laburnum Avenue and Hermitage Road (1892); Richmond Howitzers at Harrison, Park and Grove avenues (1892); Confederate Soldiers and Sailors at Libby Hill (1894); Gen. William “Extra Billy” Smith in Capitol Square (1906); and Gen. J.E.B. Stuart (1907), Confederate President Jefferson Davis (1907), Gen. “Stonewall” Jackson (1919) and Admiral Matthew Fontaine Maury (1929), all on Monument Avenue. Finally, just to let everyone know that nothing had changed, Gen. Fitzhugh Lee in Monroe Park (1955).

And then there are the city’s many streets, squares, bridges and buildings named after Confederate figures.

Mayor Stoney had it right when he described the Confederate statues on Monument Avenue as “equal parts myth and deception … a false narrative etched in stone and bronze more than 100 years ago — not only to lionize the architects and defenders of slavery, but to perpetuate the tyranny and terror of Jim Crow and reassert a new era of white supremacy.”

Clearly, statues and monuments are created to honor a person or cause. They are taken down when those in power no longer want to continue that honor. This is why there are no statues of Adolf Hitler in Germany. In fact, it’s illegal to display a fascist symbol in either Germany or Italy.

Other U.S. cities understand this: New Orleans, Orlando, Tampa, St. Louis and Charlottesville all have taken down or are in the process of taking down their Confederate statues. Other cities are renaming streets, parks and buildings. But not Richmond. Richmond wants to add “context.”

What is most revealing is how Richmond deals with its brief, three-and-a-half-year Confederate past as opposed to its three decades as the epicenter of the U.S. domestic slave trade. It took a nearly 10-year community struggle to force the state of Virginia to remove a Virginia Commonwealth University parking lot from the city’s African Burial Ground. It took a bitter two-year community campaign to stop former Mayor Dwight C. Jones and the powerful business coalition Venture Richmond from building a baseball stadium in the heart of the Shockoe Bottom slave-trading district. (Former Mayor Jones also is on record as opposing taking down the statues.) That fight forced former Mayor Jones to begin a project to memorialize just one of nearly 100 slavery-related sites in the Bottom, but Mayor Stoney is resisting the overwhelming community demand for a more inclusive — and less expensive — 9-acre Shockoe Bottom Memorial Park.

The most disturbing thing about the way the city is handling these related issues is its utter insensitivity to the black community. What kind of compromise can be reached between those who still honor the men who defended slavery and the descendants of those who were enslaved? Do you really think that some signage will make it less painful for the descendants to walk, cycle or drive past those tributes to the men who fought for the right to keep their ancestors enslaved? Whose sensitivities matter more here? Whose matter at all?

The mission of the Monument Avenue Commission as it now exists is unacceptable. It begins with a decision to compromise on the question of what to do about the Confederate-honoring, Lost Cause mythology-promoting statues on the avenue before any public meetings have taken place. The mayor has said that taking the statues down is off the table. Not one of the commission’s 10 members has publicly called for their removal. Several previously supported the effort to put a stadium in the Bottom. And the commission is preparing to shepherd a discussion about Monument Avenue while apparently ignoring the parallel issue of Shockoe Bottom.

Therefore, we are calling on the members of the commission to do the following before their first public hearing on Wednesday, Aug. 9:

• Publicly declare that taking down the statues is one of the options to be considered.

• Invite onto the commission Richmonders who already have called for the statues to be removed.

• Invite New Orleans Mayor Mitch Landrieu to speak at the first public hearing. His eloquent statement on why his city has taken down its Confederate monuments has become a classic argument for their removal.

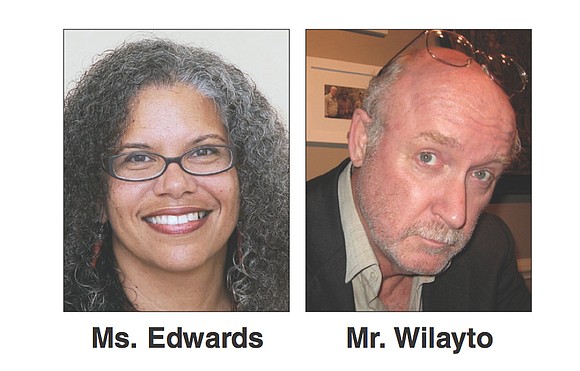

Ana Edwards is chair of the Sacred Ground Historical Reclamation Project. Phil Wilayto is editor of The Virginia Defender.