Remembering history

Member of ‘Little Rock Nine’ talks about his experience desegregating Central High School 60 years ago

9/29/2017, 6:38 a.m.

By Milbert O. Brown Jr.

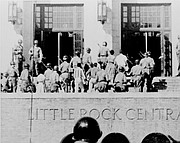

On Sept. 25, 1957, Ernest Gideon Green and eight other African-American teens were escorted by federal troops past an angry white mob and climbed the front steps to enter Central High School in Little Rock, Ark.

The teens would forever become known as the “Little Rock Nine” for their courage in helping to tear down the walls of segregation in public schools in the United States.

In the 60 years since, generations of children — especially African-American students trapped in the snare of educational inequity — would follow the trail blazed by the nine beacons and be uplifted by the physical and emotional risks they took to illuminate pathways of opportunity.

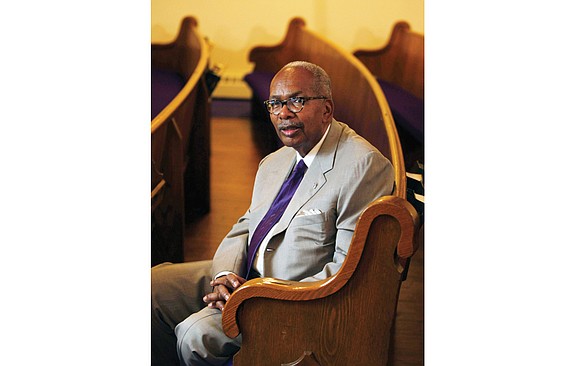

Mr. Green, now 75 and a resident of Washington, D.C., reflected recently on his catapult into history and the Little Rock Nine’s pioneering efforts in one of America’s major civil rights confrontations.

After a year of fear at the overwhelmingly white school, Mr. Green would become Central High School’s first African-American graduate in 1958. Decades later, in 1999, President Bill Clinton, an Arkansas native, presented Mr. Green and the other Little Rock Nine members with the Congressional Gold Medal, the nation’s highest civilian honor.

At a ceremony Monday in Little Rock marking the anniversary, Mr. Green and the seven other surviving members of the Little Rock Nine were honored at the school, where former President Clinton and historian Henry Louis “Skip” Gates Jr. spoke.

Next to the eight was an empty chair draped with a sash of gold and black, Central High School’s colors, in honor of Jefferson Thomas, who died in 2010.

“I feel like I’m visiting a religious shrine,” Dr. Gates said. “This is a shrine and these are the saints,” he said, praising the nine for their courage in the face of angry mobs who opposed integration of the then all-white school.

In an interview, Mr. Green said the ugliness of the city where he grew up remains just beneath the surface.

“If you scratched Little Rock deep enough, racism comes out,” he said.

Mr. Green hails from Little Rock’s central district and skipped a grade early on in his education.

“If you came to the first grade and you could read, they bounced you on to the next grade,” he said.

His mother was a schoolteacher and his father worked as a janitor at the post office. Mr. Green was the oldest of three children, but had to become a man faster than he would have wanted at 13 when his father died. Because of his mother’s limited teaching income, Mr. Green took a job during the summer to help support the family.

“I worked at a Jewish country club because, in Little Rock, the other country clubs wouldn’t accept anybody that wasn’t a white Christian,” he said. “I handed out towels, mopped the floors and kept the place reasonably clean.”

A socially conscious student, Mr. Green said he was aware of the racial storm brewing across the nation.

“I remember the picture vividly in JET magazine of Emmett Till laying in a coffin. Jackie Robinson breaking into baseball and the Montgomery bus boycott were all indications of what was going on and how black people were at the forefront of some of those changes,” he said.

On May 17, 1954, the U.S. Supreme Court declared in the Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kan., case that the “separate but equal” policy of legalized segregation was unconstitutional in America’s public schools.

However, Little Rock’s city fathers attempted to take a moderate approach to the decision and drag their feet on desegregating schools. But they were pushed by Daisy Bates, president of the Arkansas NAACP, and the organization’s members. Mrs. Bates and her husband owned the black weekly newspaper, the Arkansas State Press.

The Board of Education then asked if any Negro students were interested in transferring from an all-black school with limited resources to the all-white Central High School. Nine students signed up. But when they tried to attend, they were confronted by angry white mobs.

It was intimidating, Mr. Green recalled.

“People would be hollering, using every use of the N-word they could figure out. Arkansas Gov. Orval Faubus called in the Arkansas National Guard to keep us out, then they used the local police, who couldn’t keep the mob in order. Finally, President Eisenhower sent the troops in.”

After two weeks of the African-American students being barred from entry, President Dwight D. Eisenhower sent units of the 327th Infantry, 101st Airborne Division, to escort the students into the school. The president, a conservative and reluctant supporter of civil rights, became the first president since Reconstruction to use federal troops in support of civil rights.

Once inside, the Little Rock Nine faced challenges that would test their resolve.

“It was inside the school when we were really harassed,” Mr. Green said. “They would throw steamed wet towels our way, and at night we would get threatening phone calls.

“One of the conditions imposed on us was that we couldn’t do any extracurricular activities, which meant no sports or club memberships.”

Mr. Green credits his training as a Boy Scout with giving him the awareness and endurance to deal with the daily confrontations at school. A year before attending Central High School, he had become an Eagle Scout through Troop #73 at Mount Zion Baptist Church. His neighbor, Louis Brunson, was the scoutmaster.

“Being an Eagle Scout helped me to navigate and realize the importance of what we were doing once we finally got into Central,” Mr. Green said. “It also gave me some perspective of how we (the Little Rock Nine) were viewed and our importance in terms of history.”

He said Mrs. Bates was helpful in getting them through the year.

“Daisy was a tough lady,” he recalled of the newspaperwoman. “She was willing to use the pen, as well as her connections around the state.”

In the spring of 1958, Mr. Green became the first African-American student to receive a diploma from Central High School. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. attended the graduation, sitting with the Green family.

He fondly remembers Dr. King and Mrs. Bates visiting his home after the ceremony.

“As the family set the table with fried chicken, corn on the cob, lemonade and sweet potato pie, Dr. King expressed how proud he was that I had completed the year,” he said. “Dr. King and I didn’t talk too long because I was trying to get out with my buddies and celebrate.”

Mr. Green was awarded a scholarship to Michigan State University from an anonymous donor. Years later, he discovered the donor was John A. Hannah, president of the university and the first chairman of the Civil Rights Commission under the Eisenhower administration.

“I guess he thought that this was something he could do and I’m grateful that he did,” Mr. Green said. “Funny thing, in my role as student leader, I picketed President Hannah’s home many times during the height of the early 1960s Civil Rights Movement,” he said with a laugh.

On campus, he served as NAACP chapter president and a member of the student government.

“We were in support of the students in the South, the lunch counter sit-ins and voter registration. The city of East Lansing (Michigan) had a restriction on selling homes to black folks, so we picketed in East Lansing as well,” he said.

In 1961, he and five other young African-American men were founding members of Omega Psi Phi Fraternity’s Sigma Chapter at Michigan State.

“I saw Omega has a way to expose to the university that there were solid African-American males that could make a contribution,’’ Mr. Green said.

After graduation from Michigan State University with a bachelor’s in social science and a master’s in sociology, Mr. Green began his professional career. His first job was working for the A. Phillip Randolph Education Fund in New York City. His boss was Bayard Rustin, key organizer of the 1963 March on Washington.

Mr. Green said Mr. Rustin “was a great person to work with. We were preparing young brothers for the building trades as electricians, plumbers and steamfitters. My job was to help place applicants in an apprenticeship program and to get their union cards.”

Mr. Green later was appointed assistant secretary of labor by President Jimmy Carter. In a later career change, he became a managing director at Lehman Brothers Holdings Inc.

“It was my relationships that I established with job training programs that allowed me to have a client base on the municipal and public finance side,” Mr. Green said.

In many ways, Mr. Green sees his life as having come full circle, from hurtling educational barriers in Little Rock to attending meetings at the White House.

The Little Rock Nine students, he said, “recognized the importance of being at Central, and the manner in which folks tried to keep us out underscored how important this was for us as black students. They worked so hard to keep us away (that) it confirmed to me that we were doing the right thing.”

On the grounds of the State Capitol in Little Rock, an inscription on a plaque about their courageous efforts mirrors Mr. Green’s sentiments about his experiences: “We wanted to widen options for ourselves, and later for our children.”