Historian works to humanize the enslaved who built Monroe

Lisa Vernon Sparks Daily Press via Associated Press | 8/9/2019, 6 a.m.

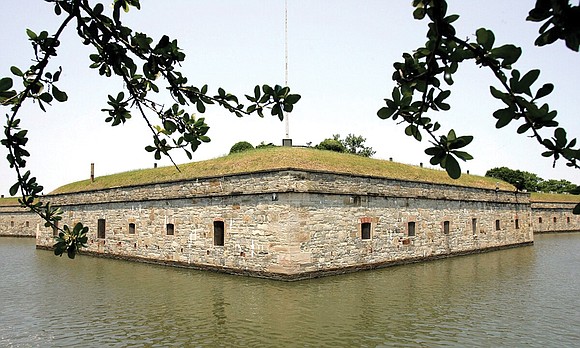

A trove of historical records tells that Fort Monroe in Hampton was built on the backs of thousands of enslaved Africans.

But little was known about their identities or who they were — until now.

Meet Amos Henley, 23. Skilled, but unpaid for his efforts, Mr. Henley was among hundreds of enslaved people leased out to the Army by their owners, who fetched a tidy sum for their work. The enslaved labored between 1820 and 1824 during the days when the foundation of the stone fortress was laid.

Mr. Henley, who worked on a barge crew daily from sunrise to sunset, died in 1821 during an accident while hauling stone with a windlass crank at Old Point Comfort.

Notably, there is a primary record of his story and other enslaved laborers that includes first and last names — significant because it was created in a register some 50 years before the first African-Americans, except for free black people, were counted in a U.S. Census.

The register, handwritten entries in two books, is the subject of a recently published paper, “Humanizing the Enslaved of Fort Monroe’s Arc of Freedom,” written by Casemate Museum historian W. Robert Kelly.

Mr. Kelly was the featured speaker and presented his paper recently during a spring meeting of the Afro-American Historical Genealogy Society of Hampton Roads at the Hampton Public Library.

The three-section paper, published in the “Journal of Contemporary Archival Studies,” is work-in-progress research that explores several entries recorded by the Army Corps of Engineers between 1819 and 1917.

It highlights research about the full names of the enslaved and their work, letters sent to chief engineers and copies of reports at Fort Calhoun/Wool and Fort Monroe, among other entries.

For Mr. Kelly, discovering a manifest of enslaved laborers not only weaves in another layer about the fort’s history, it humanizes the African-Americans who built the country’s largest stone fort.

“It’s a well-known fact that slave labor was used to construct Fort Monroe. What makes this so significant is we know actually what tasks they were doing and we are beginning to learn who they were. That’s important,” Mr. Kelly said. “It’s groundbreaking research that we intend to continue ... to make accessible to the public, to make searchable, to make usable.”

Meticulous entries, one called “Register of Work Done by Slave Labor at Fort Monroe,” lists first and last names of the enslaved, owners, rates of pay the enslaved earned for their owners monthly, the number of days worked and daily routines. Less frequently, details about the enslaved, such as who was “absent, sick, discharged, deserted or died,” also were recorded, Mr. Kelly wrote.

The register, with some 300 names of enslaved people and 50 owners during the 1820s, offers a view into those lives.

Adding a name to a face of those contributions begins to pave “the way for future generations of enslaved people to experience Fort Monroe not as a labor camp, but as Freedom’s Fortress,” Mr. Kelly wrote, alluding to decades later when thousands of enslaved people sought refuge at the fort.

Ultimately, Mr. Kelly and volunteers who are transcribing the register into an Excel database, want to make the data accessible to the Hamp- ton Roads area for families engaged in genealogy projects, he said.

The Hampton Roads chapter of the AAHGS is an affiliate of the national organization, which fosters and encourages historical and genealogical studies of all ethnic groups, with special emphasis upon Afro-Americans, according to its website.

Stephanie Thomas, president of the local chapter, welcomes the timeliness of Mr. Kelly’s work to provide another tool for the community.

Mr. Kelly said he learned about the registry by chance during a trip the National Ar- chives at Philadelphia several years ago. The research trip in 2014, paid for by the Fort MonroeAuthority, was to gather more data about the history of the fort, which was decommissioned in 2011.

After spending hundreds of hours pouring over documents, discovering the registry was an eye-opener, Mr. Kelly said. The earliest recorded listings of African-Americans did not happen before the 1870 Census.

Prior to that, enslaved Africans were only listed as a number, said archivist Patrick Connelly, who works at the Philadelphia field office.

The 300-page register inside two thickly bound books has been there for decades among 105,000 cubic feet of materials housed at the field office, he said.

In his 20 years working at the archive, Mr. Connelly said the register had not had much traction among researchers — if any. Mr. Connelly added he was happy to tip Mr. Kelly to it.

It was rare to see any federal registry listing enslaved persons, let alone both first and last names, Mr. Connelly said.

“That’s the incredible part,” Mr. Connelly said. “You could think of them as individuals and not as property, which is what they were. With that last name, it makes them more human.”

Mr. Kelly’s three-part paper notes the names of the enslaved, many of which are surnames associated with the Tidewater region. The paper also describes the rates of pay slaves earned for their owners — on average $9 per month, per enslaved person.

Other parts of the register contained documented evidence of the existence of skilled slave labor, including “bricklaying and masonry,” with information about engineers contracting a land owner who owned “black laborers” to provide services, Mr. Kelly wrote.

The second section of Mr. Kelly’s paper focuses on the fort’s Civil War era and the formerly enslaved who were accepted to the fort under Union Gen. Benjamin Butler as contraband of war and began working there.

The third section reviews the preliminary findings and how this primary source information may be incorporated into exhibits at the Fort Monroe Visitors and Education Center, possibly with an interactive display and computer archival access for the community.

“It give us all kinds of opportunity,” Mr. Kelly said. “It’s important we tell the whole story.”