Faces of COVID-19

Reginald Stuart | 4/9/2020, 6 p.m.

Virginians of all walks of life have been impacted by thecoronavirus,theairbornerespiratoryillnessthathas stricken more than 3,600 people in the Commonwealth and resulted in 75 deaths as of Wednesday.

Their passing impacts their families and the larger communities in which they worked, volunteered, worshipped and lived.

Here are some of their stories.

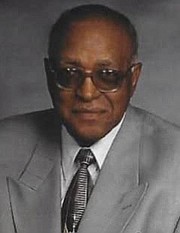

Phillip DeBerry

For Richmond native Phillip DeBerry, taking command of the highways with a sense of skill and patience was a way of living for nearly half a century.

Mr. DeBerry had been a Greyhound bus driver since 1975, delivering thousands of passengers to destinations along the East Coast from New York City to the Carolinas and countless points in between. He never had a wreck, a negative encounter with a passenger or got a traffic ticket, said Shelia Abernathy, his companion for 45 years until his death on March 28 from the coronavirus.

“He never met a stranger,” Ms. Abernathy said. He was known to go the extra step when needed, without being asked.

On more than one occasion, she said, he would have on the bus a young mother with a child or two, with one or both of the children crying from apparent hunger. At a stop, he would offer the family food paid for out of his pocket to settle their stomachs and make the bus ride more endurable. That was his style, his character, she said.

Mr. DeBerry, who was 72, was an alumnus of Armstrong High School. He got his start driving in the early years of integrated interstate bus travel. In the 1960s and before, Greyhound and Trailways did not hire racial minorities as drivers and enforced rigid racially segregated seating on the buses, in bus stations and their dining areas and restrooms.

By the time Mr. DeBerry came of age, racial discrimination practices had been outlawed and African-Americans and other minorities across the South were being recruited and hired as drivers. As he honed his skills as a driver of the huge 45-passenger Greyhounds, he was offered a job on the company’s driver training staff.

The opportunity was offered by Paul Wright, a fellow Richmonder who had been a Greyhound driver longer and had been promoted to manager and supervisor of Greyhound’s driver instruction program, Ms. Abernathy said.

Mr. Wright, who had gone with Mr. DeBerry for a training class in New Jersey, also died of the coronavirus.

Ms. Abernathy recalled a trip to Las Vegas the couple made. They happened to be there at the same time as singer James Brown, one of Mr. DeBerry’s favorite entertainers.

“He managed to get tickets to see James Brown,” making the whole excursion worth it, she said.

“He loved music, loved travel, loved casinos and loved life,” she said. “He was too young,” she said, adding that his passing “came too soon.”

In addition to Ms. Abernathy, Mr. DeBerry is survived by two sons, Phillip and Daryl.

A memorial service is being planned for a date to be determined later.

Sterling Matthews

Richmond native Sterling Mat- thews was looking forward to turning 61 on April 13. He also was making retirement plans with his wife of 44 years, Alice Allen Matthews, his high school sweetheart.

A federal contract specialist at Fort Belvoir, his death on March 31 has prompted Mrs. Matthews, a state of Virginia employee, to revisit their plans, she told the Free Press.

“God will make sure I’m going to be fine,” Mrs. Matthews hastened to add in a tone of confidence. She said she still has a son, family and friends to call on. “It may take me a while” to make the transition to her new life, she said.

Mrs. Matthews said her husband was actively involved in Moore Street Mis- sionary Baptist Church on Leigh Street. There, he served as a deacon, taught in the Sunday School and sang in the G.G. Campbell Male Chorus. He was one of three members of Moore Street whose deaths have been attributed to COVID-19.

Outside of church, he won praise over the years from the Alpha Phi Alpha Fraternity for his work as a volunteer mentor for boys and young men. The fraternity championed a successful ef- fort to have President Obama award Mr. Matthews the Presidential Volunteer Service Award in 2014.

A gospel and rhythm and blues music fan, Mr. Matthews also loved to fish, Mrs. Matthews said. Their son, Jammal, gave his dad an Alaskan fishing trip a few years ago. The trip allowed visitors to icepack their catch and ship it home, said Mrs. Matthews, ticking off a list of seafood he caught, producing enough to serve several tasty meals.

Last month, with a cough annoying him, Mr. Matthews and his wife went to an area hospital on a Monday, where doctors determined he had pneumonia. They gave him antibiotics and sent him home. By Friday of that week, Mr. Matthews was not getting better. He was hospitalized for more intense care. On March 31, he succumbed to COVID-19.

In addition to his wife and son, Mr. Matthews is survived by his parents, Sterling and Gloria Matthews; two sisters, Cynthia Folsom and Pamela Purcell; a niece, Michell Lyons, and her two children; and one granddaughter.

Robert N. Hobbs Sr.

Robert and Sue Hobbs had known each other since their high school days in the late 1940s in Richmond, yet had not seen each other for nearly half a century until they met again at a combined 50th reunion for Armstrong and Maggie L. Walker high schools.

A year later in 2013, they became husband and wife, melding the families they had created during the years in between.

Mr. Hobbs, who had joined the Marines in 1952 soon after finishing high school and was honorably discharged in July 1973 as a master sergeant, didn’t like to talk much about his military service.

From what he did share, people around could appreciate that he suffered with physical and mental scars that needed regular care. They were wounds dating back to his flying on military helicopter rescue missions that included some crashes. Many runs were into enemy territory in which he unknowingly was exposed to the toxic chemical Agent Orange. That chemical would affect his physical and mental health for the rest of his life, his medical records show.

Mr. Hobbs lived for years with sporadic, uncontrollable seizures followed by a growing number of ailments that left him vulnerable and unable to combat the progressive dementia that plagued him in recent years.

“He was a friendly, loving kind of person,” said Mrs. Hobbs, who was his third wife.

His health history didn’t bother her. “I stuck with him of course,” she said. “I loved my husband and it was my duty.”

Her husband was in long-term care at Canterbury Rehabilitation & Health- care Center in Henrico County. He first entered in 2018 when it was known as Lexington Court. He was assigned a room on the second floor with others diagnosed with dementia.

Ahighlight for Mr. Hobbs was frequent visits from his stepson Kevin Stubbs, owner of Not Just Junk Removal. Mr. Stubbs gave his stepdad regular haircuts and proudly slicked his nearly bald head with scalp moisturizer.

Mr. Stubbs said his last visit to see Mr. Hobbs was on March 7 when his stepfather began experiencing some renewed respiratory problems.

As reports of the spread of COVID-19 began, the Henrico facility shut its doors to visitors on March 13, the family said. It stepped up health security measures as health officials advised.

The facility also began setting up video chat opportunities for patients’ families, but things were going downhill for Mr. Hobbs. Mrs. Hobbs and her family were unable to connect with the overwhelmed nursing station, despite attempts on both ends.

On March 29, Mr. Hobbs, who had been moved to a hospital, died. He is one of the 32 Canterbury patients who state officials have said succumbed to the coronavirus.

“We got a call (just hours before Mr. Hobbs died) from Canterbury saying they were doing their best,” his stepdaughter, RaJean Taylor, told the Free Press

In addition to his widow and two step- children, Mr. Hobbs is survived by three sons, Robert Jr., Scott and David Hobbs, and another stepson, Lamont Stubbs.

A burial at Quantico, the U.S. Marine base in Northern Virginia, is set for a later date, the family said.