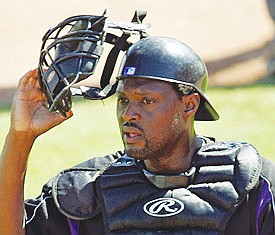

Where are the African-American catchers in MLB?

Fred Jeter | 6/4/2020, 6 p.m.

African-American baseball catchers are a vanishing breed.

It’s common during this time of the coronavirus to see black boys and men wearing masks at grocery stores, gas stations, banks, post offices, just about everywhere.

Everywhere, that is, except behind the plate in baseball.

With masked attire now prominent in the news, let’s review baseball’s masked men—the catchers—or more specifically, the rarity of African-American catchers.

The last everyday African-American big league catcher was Charles Johnson, who retired in 2005. A two-time All-Star, Johnson won four Gold Gloves in a 14-year MLB career with six different teams.

The pipeline that took Johnson to the top of the baseball world would seem to be clogged, however. Baseball has lost popularity among young African-Americans in the United States, with the catcher’s position the least popular of all.

At the start of the 2019 major league season, only 7.7 percent of baseball players were African-American, none being starting catchers.

Most of the MLB people of color wearing a mask, chest protector and shin guards are from Latin America, including Puerto Rico, the Dominican Republic, Venezuela and more. There are various reasons suggested for the lack of African-Americans signing up for the position known as “hind-catch” on the sandlots.

Cost: In many cases, catchers have to supply their own gear. A full set might run from about $135 to $300. Plus, it’s cumbersome to haul around if there is a transportation issue.

Role models: Youngsters like to identify with a pro player they watch on television. Because there essentially are no African-American catchers in the pros, it makes for difficult comparisons.

Ask a young prospect to name a single black catcher in the big leagues, past or present, and he or she may not have an answer.

Speed: Fair or not, catch- ers often are viewed as the slow kid who isn’t quick and agile enough to handle another spot. That doesn’t do much for a young man’s street cred.

African-Americans signing up for baseball tend to be among the faster kids on the team.

Brain game: Sadly, some coaches may have stereotyped black prospects as too athletic to play catcher, and not cerebral enough to call the pitches from behind the plate. This insult would be similar to how African-Americans were slow in gaining roles as football quarterbacks.

There have been some great catchers in big league baseball, but you’ve got to turn back the clock to find them.

Moses Fleetwood Walker: He debuted behind the plate with the Toledo Blue Stockings in 1884.

Roy Campanella: The first black catcher in the modern era in 1948, he won three MVP awards with the Brooklyn Dodgers.

Elston Howard: He was a 12-time All-Star, sharing the Yankees’ catching spot with Yogi Berra. Howard also played left field.

John Roseboro: He became Campanella’s successor as the Dodgers' catcher. He also was behind the plate for three Los Angeles World Series titles.

Earl Battey: He was a five-time All-Star and three-time Gold Glove winner with the Minnesota Twins.

Numerous other players of color have come from the Caribbean. That group includes Ivan Rodriguez, Elrod Hendricks, Paul Casanova, Manny Sanguillen, Benito Santiago and Tony Pena.

Currently, Yadier Molina from Puerto Rico is the standout catcher for the St. Louis Cardinals and Salvador Perez of Venezuela with the Kansas City Royals. Then there’s the Los Angeles Dodgers’ backup catcher, Russell Martin from Canada.

Charles Johnson, born in Fort Pierce, Fla., played in 1,160 big league games, all but one at catcher. That one time was when he was the designated hitter with the Baltimore Orioles. He finished his career with the Tampa Bay Rays in 2005 with the reputation as one of the best defensive catchers in history.

To steal and modify a line from Simon & Garfunkel’s song, “Mrs. Robinson,” “Where have you gone Charles Johnson? Our nation turns its lonely eyes to you ... woo, woo, woo.”

Johnson left a big mask to fill, and so far, no one has.