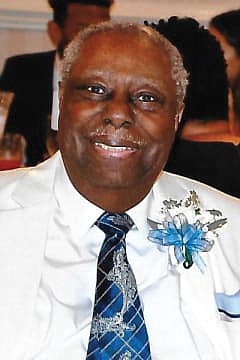

Charles L. Conyers, consummate educator and retired state education administrator, dies at 92

Jeremy M. Lazarus | 9/3/2020, 6 p.m.

Charles Lee Conyers believed that a good education was the ticket out of poverty.

The son of a sharecropper, Mr. Conyers used his own education to become an educator and then spent 42 years trying to help other children from poor families gain the knowledge they would need to create successful lives.

As a staff member with the Virginia Department of Education for 26 years, Mr. Conyers earned recognition for his work to ensure schooling for children of migrant workers picking farm crops and played a key role in ensuring billions of dollars in federal Title I assistance were used to address the learning needs of low-income children in school districts across the state.

“My father touched a lot of lives as an educator,” said his son, Dr. Charles C. “Corky” Conyers of Chesterfield County, a federal government employee and adjunct professor at Howard University in Washington.

“He got kids to go to college who never had imagined that was for them and found scholarships for them,” Dr. Conyers said.

A passionate grill master who loved cooking for others, Mr. Conyers’ efforts to lift others are being remembered following his death on Tuesday, Aug. 25, 2020, at his Richmond residence. He was 92.

The family held a private graveside service Tuesday, Sept. 1, at Forest Lawn Cemetery.

His death occurred seven months after that of his wife of 67 years, Mary Foster Conyers, a retired reading specialist for Richmond Public Schools.

Born in Cyrene, Ga., a rural community near the Florida border, Mr. Conyers was a beneficiary of his family’s push for education, his son said.

His sharecropper father, Luther H. Conyers Sr., only had a fourth-grade education, Dr. Conyers said, but helped lead the effort to develop a Rosenwald School in a nearby community to ensure his children got more education than he did.

Mr. Conyers graduated at age 15 and started classes at what is now Savannah State University. Before he could complete his degree, he was drafted into the Army. During his service, his son said he taught fellow soldiers to sign their names so they could cash their checks.

After his military service, Mr. Conyers returned to Savannah State and graduated in 1949. He would later earn a second bachelor’s degree and a master’s from Virginia State University.

With his diploma and agricultural experience, Mr. Conyers landed his first job in Virginia in 1950. Clifton Jeter of the state Department of Education recruited him to work with returning Black veterans at a segregated regional training school in Culpeper.

Before securing a position with the state and moving to Richmond in 1966, Mr. Conyers taught in agricultural programs in Madison, Accomack and Louisa counties and served as principal of CentralAcademy in Botetourt County and the John J. Wright Consolidated School in Spotsylvania County.

He started at the state Department of Education as a supervisor of compensatory education where his son said he focused on aiding educationally underserved communities.

Mr. Conyers became the first Black director in the department to manage a budget when he was promoted to manage the state’s migrant education programs, Dr. Conyers said. In an innovation that was later adopted nationally, he sought to make sure that student educational and medical records flowed more easily as families crossed state lines to harvest vegetables and fruits.

“He implemented cooperative agreements up and down the East Coast to make that happen. That was his baby,” Dr. Conyers said, “and a lot of children benefited.”

Mr. Conyers moved up to director of Virginia Title I programs in the late 1970s. In that post, he oversaw the flow of federal funds that provide extra funding to school districts to undertake such activities as improving curriculum, bolstering instruction, providing remedial services, engaging parents and serving homeless and foster children. The funding goes to schools where 40 percent or more of students qualify for free or reduced price lunches.

“He was very disciplined and organized” in carrying out his duties, his son said, and “he was an absolute stickler on time. He didn’t like people showing up late, and he made sure he was always on time.”

Mr. Conyers was serving as president of the Theban Beneficial Club at the time of his death and was a past president of the Iota Chapter of Phi Beta Sigma Fraternity.

He also was a longtime member of First African Baptist Church, where he served as a deacon, participated in Sunday Bible study and was best known as the head chef of the Culinary Arts Committee, which staged barbecues and fish frys.

He also staged an annual cookout on Jan. 1 at his North Side home. “He was the life of the party. My parents would open their home and feed all comers,” Dr. Conyers said.

He recalled his parents rolling out the welcome mat for schoolmates. “They always came to our house. When there were snowstorms, they wanted to get snowed in at my home.”

In addition to Dr. Conyers, survivors include Mr. Conyers’ son, Brian K. Conyers of Atlanta; a brother, Luther H. Conyers Jr. of Georgia; and four grandchildren. A third son, Andrei “Bernie” Conyers, died in February.