African-Americans made their marks at early Olympics

7/22/2016, 1:30 p.m.

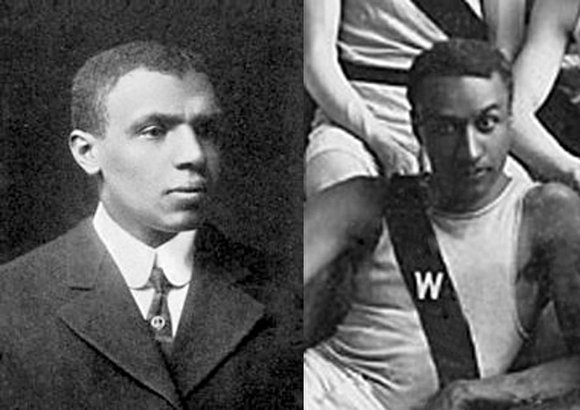

When it comes to inclusion of African-American athletes, the U.S. Olympic track and field team got nearly a half-century head start on other high-profile sports. In 1904, George Poage became the first African-American to represent the United States in the Olympic games. The event was held that year in St. Louis, in conjunction with the World’s Fair.

Having graduated from the University of Wisconsin with a degree in history, the 24-year-old Poage made history of his own in St. Louis, winning bronze medals in the 200- and 400-meter hurdles. He also raced in the 60-meter dash trials.

There were no black Americans at the 1896 Olympic games in Athens or the games in Paris in 1900.

However, a black Frenchman, Constantin Henriquez, who was born in Haiti, won a gold medal for rugby union in Paris.

Poage was born in Hannibal, Mo., and lived most of his early life in La Crosse, Wis., where he graduated as the class salutatorian from La Crosse High School.

At the University of Wisconsin, he became the first African-American Big 10 Conference track champ with victories as a hurdler.

Poage faced hurdles off the track, too.

The St. Louis Olympics and World’s Fair were tarnished by Jim Crow laws that mandated segregated facilities for white and black spectators.

Poage was pressured by black groups to boycott the Olympic games in protest, but he chose to compete anyway, preferring to let his fast feet make a statement.

Four years later, at the 1908 London Olympics, John Baxter Taylor became the first African-American gold medalist when he ran the third leg on the victorious United States 4x400 relay team.

Taylor, who was born to former slaves in Washington, also ran the individual 400-meter race in London in perhaps the strangest ending to any Olympic event ever.

After winning his quarterfinal and semifinal heats, Taylor was a favorite among four finalists to win the 400.

However, during the race, American John Carpenter was charged with obstructing British runner Wyndham Halswelle, and officials ruled that the race be repeated — without Carpenter.

As a show of support, Taylor and William Robbins declined to run again and Halswelle won the medal running alone.

Tragically, Taylor, who graduated from the University of Pennsylvania with a degree in veterinary medicine, died a few months after the 1908 Games of typhoid fever. He was 26.

All-white delegations from Cuba and South Africa competed in the Olympics beginning in 1896, but few other Caribbean and sub-Saharan African nations were present.

Following World War II, Olympic organizers reached out to make the games truly global. Ethiopia and Kenya joined the competition in 1956 and began producing an assembly line of long distance gold medalists

At the 1960 Olympics in Rome, Ethiopia’s Abebe Bikila was the first champion from a sub-Saharan African nation.

Caribbean nations, including Jamaica and Trinidad, began sending teams to the Olympics in 1948 with some of world’s fastest sprinters.

Jamaican Arthur Wint became the first Caribbean champ with a 400-meter victory at the 1948 Olympic games in London.

Team USA will include a large number of African-American athletes at this year’s games in Rio de Janeiro. African-Americans will be competing not only in track and field, but also in gymnastics, boxing and basketball.

But it was Poage who got there first and made a lasting mark.

Later in life, Poage taught at the all-black Charles Sumner School in Milwaukee, worked on a farm in Minnesota and for the last 20 years of his professional life was a postal clerk in Chicago.

Because the Olympics were strictly amateur events in those days, Poage never cashed in financially on his St. Louis achievements.

Under his photo in the University of Wisconsin’s 1903 yearbook was this inscription: “Of matchless swiftness; but of silent pace.”

Poignantly, the caption would link

his dazzling speed with subsequent

years of anonymity working in Chicago at a post office.