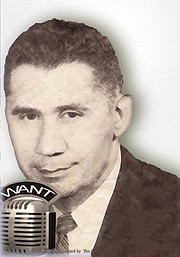

‘Tiger Tom’ hits 100

Local radio, news icon was voice of community for more than 50 years

10/28/2016, 6:58 p.m.

By Holly Rodriguez

When John “Tiger Tom” Mitchell was born in 1916, African American-owned banks, insurance companies, newspapers, barber and beauty shops and retail businesses had set a foundation of wealth for Jackson Ward.

The vibrancy of the community, and growing up around his great uncle, crusading Richmond newspaper editor John Mitchell Jr., fed Mr. Mitchell’s desire to work in the newspaper and radio businesses.

For more than 30 years, “Tiger Tom” was the popular, on-air voice at WANT-990 AM radio, spinning records, providing the latest news and sports and advertising the biggest entertainers coming to town.

For decades, he also was the voice of Friday night football games, announcing the teams and their plays at City Stadium, including the annual Armstrong-Walker Classic on Thanksgiving weekend.

While the revered radio personality and broadcasting icon retired in 1982, his clear voice and upbeat style are still remembered.

“Tiger Tom” turns 100 on Thursday, Oct. 27. He’s celebrating with family and friends this weekend at his South Side home.

“Sometimes he says he can’t believe he’s still here at 100,” his son, John, told the Free Press in an interview this week. “People stop me on the street and ask me how he’s doing. He was an institution in this city.”

Even though he is less mobile now, Mr. Mitchell reads the Free Press and daily newspapers every day. A magnifying glass sits on his bed, along with the latest edition he’s reading.

At times, his voice is as strong as it was when he was on the radio. His family encourages him to talk about the past. His recollections are packed with history.

He talks about his great uncle, the noted editor of The Richmond Planet, who organized a boycott of the city’s segregated trolley system in 1904 and ran for governor on the Lily Black ticket in 1921. He also was a founder of Mechanics Savings Bank.

Working as young man with the newspaperman, “Tiger Tom” met many of the city’s influential leaders, including businesswoman and bank founder Maggie L. Walker, who gave him his first job as a linotype printer at her newspaper, the St. Luke Herald.

In the interview, Mr. Mitchell emphasized that his great uncle and Mrs. Walker helped one another.

“They were not competitors,” he said. “They supported one another. That’s what we all did back then.”

At 14, he suffered an injury on the newspaper job — the tip of his index finger was cut off. Still, he went on to write articles for The Richmond Planet and, later, for The Richmond Afro, JET magazine and the Richmond Times-Dispatch. He also worked for The Virginia Journal, the magazine for the Virginia Teachers’ Association, the African-American teachers’ organization during segregation.

He graduated from Armstrong High School as the valedictorian of his class in 1935. He enrolled at Virginia Union University and played freshman football, but left after a year to join the military. He was turned down because of a ruptured hernia for which he had undergone surgery. He ended up working in a Civilian Conservation Corps camp in Mecklenburg County.

He later returned to Richmond and the newspaper business. He wrote about what his son calls “the other side of Richmond” — crime, police investigations and court trials.

“My father reported on the politicians and the gangsters,” John said.

One trial he covered still haunts him, John said. “It was about the Martinsville 7.”

In 1949, seven young African-American men were convicted of raping a white woman in the small Southern Virginia city near the North Carolina border. All seven were sentenced to death in the electric chair by all-white juries that deliberated no longer than two hours. The men’s appeals to the Virginia Supreme Court, and then the U.S. Supreme Court, were unsuccessful. All were put to death in 1951.

The highly controversial case drew international attention, including letters from influential people in Russia seeking a stay of their execution. Protests were held in Richmond and near the Spring Street penitentiary where the seven men and the electric chair were held.

“My father was in contact with the relatives of the men,” John said. “He has always been very passionate about the injustice in that case. The blatant racism was upsetting.

“He reads the things that are going on today and says justice is still unequal.”

In the early 1950s, Tiger Tom started working with WANT radio, the call letters of which he says stood for “With All Negro Talent.”

He worked with the station until its sale in 1982, his son said. And he was the announcer at football games from the 1960s until the early 1980s. He always enjoyed the major showdown between Maggie L. Walker and Armstrong high schools that would draw crowds up to 30,000 or more.

“As an announcer, I was neutral. But in my heart, I was favoring Armstrong,” Mr. Mitchell laughed.

Mr. Mitchell has been recognized for his days of glory. In 1996, he was inducted into the Virginia Communications Hall of Fame. In November 2009, he was inducted into the National Broadcasters Hall of Fame in Akron, Ohio.

He also has received the Frank Soden Lifetime Achievement Award from the Richmond Broadcasters Hall of Fame.

His days are quiet now, filled with the simple pleasures of family — his wife of 56 years, Elizabeth “Bette” Mitchell, sons, John and Cary, daughter, Ida, and nieces and nephews. His other daughter, Sheryl, is deceased.

He still recites poetry, and up until three or four years ago, would read books from his vast collection, making notes in the margins and on the back and cover pages.

He talks periodically by phone with friends and has visitors.

Reading newspapers, he keeps up with current events, including the upcoming election.

Of President Obama’s historic election as the nation’s first African-American leader, he said, “It’s about time.”

With Hillary Clinton poised to become the first woman president, he said, “It’s hard to believe a woman is running. I’m a Democrat and I support her.”