Sessions wants to return to tough crime policies

4/13/2017, 6:55 p.m.

By Sadie Gurman

Associated Press

WASHINGTON

For three decades, America got tough on crime.

Police used aggressive tactics and arrest rates soared. Small-time drug cases clogged the courts. Vigorous gun prosecutions sent young men away from their communities and to faraway prisons for long terms.

But as crime rates dropped since 2000, enforcement policies changed. Even conservative lawmakers sought to reduce mandatory minimum sentences and to lower prison populations, and law enforcement shifted to new models that emphasized community partnerships over mass arrests.

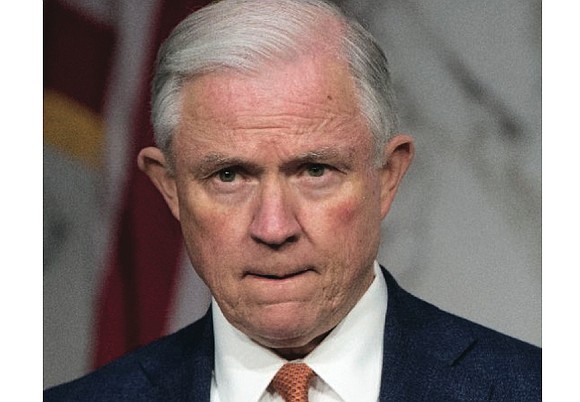

U.S. Attorney General Jeff Sessions often reflects fondly on the tough enforcement strategies of decades ago and sees today’s comparatively low crime rates as a sign they worked. He is preparing to revive some of those practices even as some involved in criminal justice during that period have come to believe those approaches went too far, for too long.

“In many ways with this administration we are rolling back,” said David Baugh, who worked as a federal prosecutor in the 1970s and 1980s before becoming a defense lawyer in Richmond. “We are implementing plans that have been proven not to work.”

Mr. Sessions, who cut his teeth as a federal prosecutor in Mobile, Ala., at the height of the drug war, favors strict enforcement of drug laws and mandatory minimum sentences. He says a recent spike in violence in some cities shows the need for more aggressive work. The U.S. Justice Department said there won’t be a repeat of past problems.

“The field of criminal justice has advanced leaps and bounds in the past several decades,” spokesman Ian Prior said. “It is not our intention to simply jettison every lesson learned from previous administrations.”

Mr. Sessions took another step back from recent practices when the Justice Department announced last week that it might back away from federal agreements that force cities to agree to major policing overhauls. His concern is that such deals might conflict with his crime-fighting agenda.

Consent decrees were a staple of former President Obama’s administration to change troubled departments, but Mr. Sessions has said those agreements can unfairly malign an entire police force. He has advanced the unproven theory that heavy scrutiny of police in recent years has made officers less aggressive, leading to a rise in crime in Chicago and other cities.

It’s the latest worry for civil rights activists concerned about a return to the kind of aggressive policing that grew out of the drug war, when officers were encouraged to make large numbers of stops, searches and arrests, including for minor offenses. That technique is increasingly seen as more of a strain on police-community relationships than an effective way to deter crime, said Ronal Serpas, former police chief in New Orleans. He was a young officer in the 1980s when crack cocaine ravaged some communities.

Officers’ orders were simple, Mr. Serpas said: “ ‘Go arrest everybody.’ We had no idea what the answers were,” he said. “Those of us who were on the front line of that era of policing have learned there are far more effective ways to arrest repeat, violent offenders, versus arresting a lot of people. That’s what we have learned over the last 30 years.”

In a recent memo calling for aggressive prosecution of violent crime, Mr. Sessions told the nation’s federal prosecutors that he soon would provide more guidance on how they should prosecute all criminal cases.

Mr. Sessions’ approach is embodied in his encouraging cities to send certain gun cases to tougher federal courts, where the penalties are more severe than in state courts, and defendants are often sent out of state to serve their terms.

He credits one such program, Project Exile, with slowing murders in Richmond in the late 1990s. Its pioneer was FBI Director James Comey, who was then the lead federal prosecutor in the area.

In the community, billboards and ads warned anyone caught with an illegal gun faced harsh punishment. Homicides fell more than 30 percent in the first year in Richmond, and other cities adopted similar approaches.

But studies reached mixed conclusions about its long-term success. Defense lawyers such as Mr. Baugh said the program disproportionately hurt the African-American community by putting gun suspects in front of mostly white federal juries, as opposed to state juries drawn from predominantly African-American Richmond jury pools that might be more sympathetic to African-American defendants.

“They took a lot of young African-American men and took them off the streets and out of their communities and homes and placed them in federal prison,” said Robert Wagner, a federal public defender in Richmond.

Mr. Baugh argued the program was unconstitutional after a client was arrested for gun and marijuana possession during a traffic stop. He lost the argument, but a judge who revealed 90 percent of Project Exile defendants were African-American also shared concerns about the initiative.

Mr. Sessions has acknowledged the need to be sensitive to racial disparities, but has also said, “When you fight crime, you have to fight it where it is ... if it’s focused fairly and objectively on dangerous criminals, then you’re doing the right thing.”

During the drug war, sentencing disparities between crack cocaine and powder cocaine crimes were seen as unfairly punishing African-American defendants. Mr. Sessions in 2010 co-sponsored legislation that reduced that disparity. But he later opposed bipartisan criminal justice overhaul efforts, warning that eliminating mandatory minimum sentences weakens the ability of law enforcement to protect the public.

“My vision of a smart way to do this is, let’s take that arrest, let’s hammer that criminal who’s distributing drugs that have been imported in our country,” Mr. Sessions said in a recent speech to law enforcement officials.

The rhetoric sounds familiar to Mark Osler, who worked as a federal prosecutor in Detroit in the late 1990s, when possessing 5 grams of crack cocaine brought an automatic five-year prison sentence.

Mr. Osler said he came onto the job expecting to go after international drug trafficking rings, but “instead, we were locking up 18-year-old kids selling a small amount of crack, and pretending it was an international trafficker.”