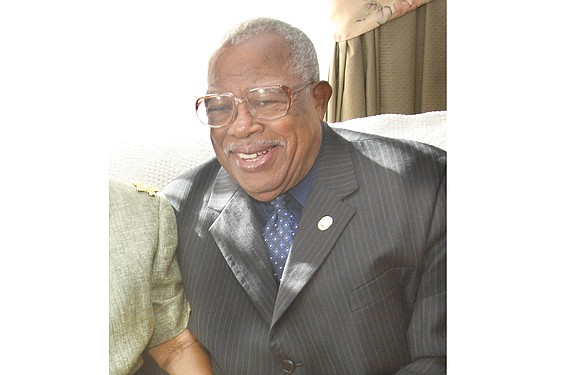

Rev. Curtis W. Harris, civil rights activist, 1st black Hopewell mayor, dies at 93

Jeremy M. Lazarus | 12/15/2017, 7:05 a.m.

The Rev. Curtis W. Harris Sr. devoted his life to battling the racism and bigotry that oppressed African-Americans in Hopewell and across Virginia.

Rising to become the first African-American mayor of a Hopewell that he helped to change, the longtime pastor of Union Baptist Church in that city fearlessly battled the status quo of segregation during the Civil Rights Movement with dogged persistence, unyielding dignity and an unquenchable faith in the righteousness of the cause.

As the leader of the Virginia Chapter of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference for 25 years, he continued the fight for equality by speaking out, leading protest marches and regularly filing complaints with federal authorities over voting rights and discrimination in schools, housing and employment.

He was a champion for public housing residents and also fought against Hopewell’s decision to place landfills and polluting factories in African-American sections of the city.

He was arrested 13 times for leading sit-ins and other protests against segregated public places and private businesses despite death threats and even an effort to firebomb his home.

Rev. Harris was unfazed, said his son, Michael B. Harris of Fort Washington, Md. “I don’t recall seeing him afraid of anything.”

The freedom fighter who marched with Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and became Dr. King’s top lieutenant in Virginia died Sunday, Dec. 10, 2017, at an assisted living center where he had lived in recent years. He was 93.

Family and friends will celebrate his life 11 a.m. Monday, Dec. 18, at First Baptist Church of Hopewell, 401 N. 2nd Ave.

His body will lie in repose from 8 a.m. to 8 p.m. Saturday, Dec. 16, at Hopewell’s Carter G. Woodson Middle School, once the high school from which he graduated. He will be placed in the atrium of the school, outside of the library that is named for him.

In a resolution honoring him, the General Assembly described Rev. Harris as “one of Virginia’s most celebrated … leaders for his unselfish and unrelenting efforts to pursue and defend the rights of others.”

Former state Sen. Henry L. Marsh III described Rev. Harris as “a warrior for civil rights” at a 2012 banquet celebrating the minister. A longtime civil rights lawyer, Mr. Marsh recalled that Rev. Harris would come to him following his arrests, and “I would tell him, ‘You know, Curtis, you could go to jail.’ He would look at me and say, ‘Well what do you think I want to do?’ ”

A full-time minister, Rev. Harris later ran seven times for the Hopewell City Council before winning a seat on the governing body in 1986, becoming one of the council’s first African-American representatives. He would hold the seat for 26 years, with the council electing him mayor in 1998. He gave up his seat in 2012 after suffering a stroke.

Born in Dendron in Surry County, he grew up in Hopewell, where his mother moved to find work after his father deserted the family.

He began working in a cotton plant, left to study at Virginia Union University, but returned to Hopewell after a year and married his high school sweetheart, Ruth Jones, with whom he had six children.

He got involved in civil rights in 1950 while working as a janitor at what is now the AdvanSix chemical plant in Hopewell.

Becoming a union shop steward and president of the Hopewell Branch NAACP, he pushed the then-Allied Chemical and Dye Co. to hire African-Americans for positions beyond the low-paid position of janitor.

Ordained as a Baptist minister in 1959, Rev. Harris was first called to pastor First Baptist-Bermuda Hundred. In 1961, he was called to pastor Union Baptist, which sat across the street from his Hopewell home, and Gilfield Baptist in Southampton County. Despite juggling a busy schedule, he led Gilfield for 33 years and retired from Union Baptist in 2007 after 45 years.

His role as pastor revved up his civil rights work. In 1960, he was arrested and sentenced to 60 days in jail for leading a sit-in at the segregated lunch counter of a Hopewell drugstore. Later that year, he protested the whites-only policy at the city’s swimming pool, which the city closed and filled with cement rather than allow African-Americans to swim.

He would continue the pace in joining protests against false arrests and crusades to push voting.

His dual role as pastor and civil rights activist also brought him in contact with Dr. King and the SCLC, which Dr. King co-founded in the 1950s. By 1961, Rev. Harris had become a member of the national board and had founded the Hopewell Improvement Association as an SCLC affiliate.

In 1963, he helped found a statewide chapter of the SCLC. That same year, he enrolled his sons Curtis W. Harris Jr. and Kenneth C. Harris as the first African-American students in the previously all-white Hopewell High School. “That was the start of school desegregation in Hopewell,” Rev. Harris recalled in an interview.

Through the SCLC, Rev. Harris worked with Dr. King on numerous civil rights initiatives, including the Selma to Montgomery March for Voting Rights in which he participated and which led to the 1965 Voting Rights Act that ensured African-Americans’ right to register and cast a ballot would be protected in Virginia and other states that had imposed severe restrictions.

He gave up the presidency of the state SCLC in 1996, but continued his service as a regional and national vice president, posts he held for another 10 years.

He was at the forefront on local issues, such as working with others in a bid to halt Hopewell from opening a landfill on property located in the African-American community.

Forty years later, he led an unsuccessful effort to halt the construction of an ethanol plant on land in the same community, decrying the potential for pollution and health problems for people living nearby.

Rev. Harris was predeceased by his wife of 65 years, Ruth, who died in 2011.

In addition to his three sons, survivors include three daughters, Joanne H. Lucas of Virginia Beach, Karen D. Bradford of Fayetteville, Ga., and Ruth Michelle Pritchett of Waldorf, Md.; 23 grandchildren; 32 great-grandchildren; and three great-great-grandchildren.