Looking back, looking forward

New photo exhibition at Black History Museum & Cultural Center of Virginia shares stories from a bygone era

2/22/2018, 9:07 p.m.

By Samantha Willis

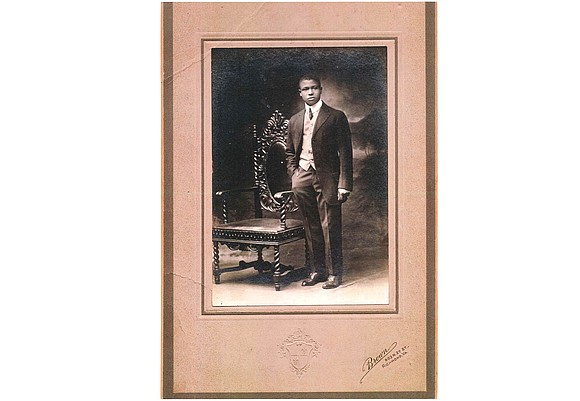

A sense of dignity emanates from the faces peering out of the searing, black and white photos mounted in the Black History Museum and Cultural Center of Virginia’s upstairs exhibition space.

African-American men and women — doctors, educators, ministers, musicians, some well known and some not — pose in carriages and automobiles, while others clutch hard-earned diplomas, eyeing the viewer confidently.

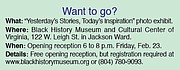

All of them gaze through time in the museum’s new photographic exhibition, “Yesterday’s Stories, Today’s Inspiration,” on display through May 2018.

“We chose the title because we know there are many historical figures people know about — Martin Luther King Jr., Rosa Parks, Barack Obama,” said Adele Johnson, the museum’s interim executive director. “And they certainly have made many contributions to American history and to black history.

However, there are many, many more who have made contributions who are unsung heroes.”

The work of two such heroes, Richmond photographers George O. Brown and James Conway Farley, features prominently in the exhibition. Both photographers are themselves part of the showing’s historically rich narratives. Mr. Brown and Mr. Farley operated Jefferson Fine Art Gallery together in Richmond starting in 1895. They won awards at the 1907 Jamestown Tercentennia, and were nationally renowned photographers “bar none,” said researcher and educator Elvatrice Belsches, the exhibition’s curator.

In the early 1900s, Mr. Brown was distinctly positioned among award-winning black photographers nationwide, including James VanDerZee of New York City and Addison Scurlock of Washington, Ms. Belsches said.

“George O. Brown began training as a photographer in the 1870s,” according to Ms. Belsches, opening his own studio, Old Dominion Gallery, after his venture with Mr. Farley.

Mr. Brown’s children, Bessie Gwendola Brown and George Willis Brown, joined their father’s business; Bessie operated the studio until 1969.

Photos by the Browns depict decades of black Richmond through the 1950s, including social and religious events, fraternal organizations and portraits of some the city’s best known citizens like banker and businesswoman Maggie L. Walker. Many of these are included in the Black History Museum exhibition.

Also on view are class photos of students at historic Richmond educational institutions such as Armstrong High School, Hartshorn Memorial College and Virginia Union University.

Ms. Belsches said the Browns’ photos in the exhibition — one shows a group of men in tuxedos, their expressions stately and dark skin gleaming against the snowy white of their shirts — span nearly 100 years.

“One hundred years of photographs, 100 years of visual storytelling; it’s simply amazing,” she said.

Michael G. Brown of Richmond, the great-grandson of George O. Brown and the grandnephew of Bessie Gwendola Brown, said he views his relatives “as visual historians.”

“They captured the lives, deaths and day-to-day experience of black people in the Richmond area,” said Mr. Brown, a political consultant and former head of the state Board of Elections.

“At the same time, they were entrepreneurs,” he said of his forebearers. “Their work left a visual record of what was happening in the black community … that they were able to survive and to move forward, irrespective of the limitations put on them by society.”

Mr. Brown’s late brother, Albert W. Brown, also chose photography as his life’s work, working for various studios throughout his career, including Miller & Rhoads and Caston Studios. He died in April 2009.

Work by other photographers, such as Frances Benjamin Johnston, whose arresting images of early Hampton University students are hauntingly beautiful, round out the collection of more than 150 photos, including a cache of rare originals.

Forgotten traditions of the community appear in the exhibition, Ms. Belsches said.

“Many people don’t know that some black churches used to have Sunday school orchestras, full bands with all of these instruments. We have a photo of Sixth Mount Zion’s Sunday School orchestra dating in 1925.”

The photographs act as a prism, casting in multifaceted ways how African-Americans lived, worked and sought to be remembered.

“There’s a pride, a determination, a persistence about these photos,” said Ms. Johnson.

Ms. Belsches agreed, adding that the photo exhibition aims to elevate the stories of the black experience as told through the lenses of black photographers.

“They’ve given us a visual, historical record, yes,” she said, “but their artistry is also on full display.”