6 Virginia tribes set for federal recognition

Free Press staff, wire reports | 1/19/2018, 6:53 a.m.

WASHINGTON

Six Virginia Indian tribes have secured congressional recognition, ending a nearly two-decade fight for official acknowledgment of their place in U.S. history.

The U.S. Senate passed a bill recognizing the tribes that was spearheaded by Virginia’s two senators, Tim Kaine and Mark R. Warner, on a surprise vote last Thursday.

The measure, which already had passed the House, now goes to President Trump for his signature. He has not publicly indicated his position on the legislation, which received bipartisan support.

If the president signs the measure, the tribes’ new status would make federal funds available for housing, education and medical care for about 4,400 members of the Chickahominy, the Eastern Chickahominy, the Upper Mattaponi, the Rappahannock, the Monacan and the Nansemond tribes.

More importantly, sponsors said, the bill would correct a long-standing injustice for tribes that were among the first to greet English settlers in 1607.

The six tribes covered by the bill were part of the Powhatan Nation, a confederation of Eastern Virginia tribes known for Pocahontas who, according to legend, saved the life of Capt. John Smith and later married the first English tobacco planter, John Rolfe.

The recognition also would allow the tribes to repatriate remains of their ancestors stored at the Smithsonian.

However, they would be barred from operating casinos.

There are currently 11 state-recognized tribes in Virginia and more than 500 federally recognized Indian tribes, many of whom navigated the U.S. Bureau of Indian Affairs process.

Only one other tribe in Virginia has been federally recognized — the Pamunkey in 2016, one of two tribes with land on a reservation in King William County.

A discriminatory state law and quirks of history blocked that path for other Virginia tribes.

The Racial Integrity Act of 1924, required that births in the state be registered as either “white” or “colored,” with no option available for Native Americans. The result is what historians have described as a “paper genocide” of Indian tribes.

Other key documents were lost in Civil War-era fires.

Delays also resulted from the tribes’ unique place in history: They made peace with England before the country was established and never signed formal treaties with the U.S. government.

The Mattaponi Indians, the other Virginia tribe with a reservation dating back to the colonial era, are pursuing recognition through the Bureau of Indian Affairs, having long ago given up on getting recognition from Congress.

The remaining three tribes secured state recognition in 2010, but have yet to meet federal criteria due to the high hurdles they face to prove lineage.

Getting the legislation passed was no easy task.

Sen. Kaine said the bill passed on a motion for unanimous consent after years of trying to get it through committee.

“We had 75 votes, but that was not enough,’ he said. “We needed all 100.”

Some opponents rejected the notion that Congress should recognize the Virginia tribes when the U.S. Bureau of Indian Affairs set up an administrative procedure to do so.

However, the chiefs said the expensive and time-consuming process effectively precluded most Virginia tribes because gaps in their records made it impossible for them to provide complete genealogies.

Some senators with tribes in their home states wanted Congress to recognize all the tribes together instead of singling out Virginia.

Still others worried federal recognition would open the door to casinos, despite language in the bill stating gaming was prohibited.

The path became a bit easier this year with the retirement of U.S. Sen. Harry Reid of Nevada. The former Democratic leader had kept the bill bottled up out of concern that Virginia Indians could be freed to build casinos to compete with Las Vegas.

To earn unanimous consent, Sen. Kaine said he had to persuade five Republicans to consent to the bill, acknowledging that some agreements were made to get it done.

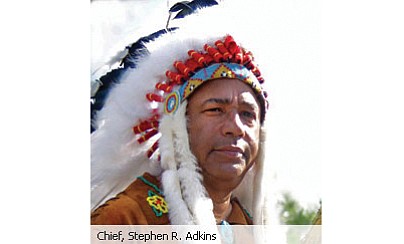

Chickahominy Indian Chief Stephen Adkins, who watched the vote from the Senate gallery, said that because of administrative roadblocks, the chiefs were once told they wouldn’t live to see the day they were federally recognized.

“We can hold our heads high as acknowledged sovereign nations within the United States of America,” he told The Washington Post by phone after the vote.

He had lobbied every session of Congress since 1999 in hopes of achieving a status that would bring both dignity and real prospects for an improved quality of life to tribal members.

The bill that passed the Senate was introduced in the House by Virginia’s 1st District Congressman Rob Wittman, a Republican, with 3rd District Rep. Robert C. “Bobby” Scott, a Democrat, among the co-sponsors.

“While I always knew in my heart of hearts Congress would do the right thing,” Rep. Wittman stated in a release, “this moment renews my faith” in the nation.

Sens. Warner and Kaine renewed the push for passage late last year and received word last Thursday morning that two of the three remaining holds had relented.

“Boy, oh, boy — this is the day we get things right on a civil rights basis, on a moral basis and on a fairness basis,” Sen. Warner said on the floor.

Sen. Kaine said several chiefs traveled to England last spring to commemorate Pocahontas, including attending a plaque dedication ceremony at the church where she is buried.

“They were treated as sovereigns, treated with respect, and all they’ve asked is to be treated the same way by the country they love,” Sen. Kaine said.