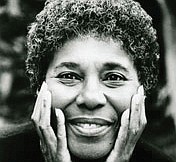

Acclaimed writer Paule Marshall, professor emeritus at VCU, dies at 90

Free Press wire, staff report | 8/23/2019, 6 a.m.

Writer Paule Marshall, an exuberant and sharpened storyteller who in books such as “Daughters” and “Brown Girl, Brownstones” drew upon classic and vernacular literature and her mother’s kitchen conversations to narrate the divides between African-Americans and Caucasians, men and women, and modern and traditional cultures, died Monday, Aug. 20, 2019, in Richmond.

Her son, Evan K. Marshall told the Associated Press that his mother, who was 90, had suffered from dementia in recent years.

Ms. Marshall, who was a professor emeritus of English at Virginia Commonwealth University, was first published in the 1950s. She was the author of nine books, her talent recognized with numerous awards including a Guggenheim Fellowship in 1961 and a MacArthur Fellowship – also known as a “genius grant” — in 1992.

VCU officials said Ms. Marshall helped bring eminent black writers — many of whom were her friends — to the campus, including Toni Morrison and James Baldwin.

“She was a person of enormous strength and dignity, a powerful sense of purpose and a clear vision of the scope of what she wished to achieve as a writer,” said Dr. Gregory Donovan, a professor in VCU’s English Department.

For years, she was virtually the only African-American woman among major fiction writers in the United States, a bridge between Zora Neale Hurston and Ms. Morrison, Alice Walker and others who emerged in the 1960s and 1970s.

Calling herself “an unabashed ancestor worshipper,” Ms. Marshall was the Brooklyn-born daughter of Barbadian immigrants and wrote lovingly, but not uncritically, of her family and other upholders of the ways of their country of origin.

From the start, she contrasted the values of Americans and other Westerners with those from the Caribbean and tallied the price of assimilation.

In “Brown Girl, Brownstones,” her autobiographical debut, a young Brooklyn woman seeks her own identity amid the conflicting values of her Bajan parents — her hard-headed mother and tragically hopeful father. In “The Chosen Place, the Timeless People,” idealistic American project workers in the Caribbean encounter the skepticism of the local community. “Praisesong for the Widow” tells of an African-American woman’s awakening during a Caribbean vacation.

“I like to take people at a time of crisis and questioning in their lives and have them undertake a kind of spiritual and emotional journey, and to then leave them once that journey has been completed and has helped them to understand something about themselves,” Ms. Marshall told the Associated Press in 1991.

Ms. Marshall’s admirers included Dorothy Parker, Edwidge Danticat and Langston Hughes, an early mentor who sent her encouraging postcards in green ink, brought her on a State Department tour of Europe in 1965 and urged her to “get busy” when he thought the young writer was working too slowly. The tour helped boost her career and profile in the literary world.

Ms. Marshall joined the VCU faculty in 1984 after a two-year stint as a writer-in-residence. She previously taught at Yale and Columbia universities, the University of California at Berkeley and at the Iowa Writer’s Workshop.

She taught at VCU until 1994, when she joined the faculty of New York University holding the Helen Gould Sheppard Chair of Literature and Culture.

She won the John Dos Passos Prize for Literature in 1989 and, in 2009, she won the Anisfield-Wolf Book Award for lifetime achievement in writing books “that have made important contributions to our understanding of racism and human diversity.”

“We are deeply saddened by the loss of a wonderful colleague and a wonderful writer,” said Dr. Catherine Ingrassia, professor and chair of the VCU English Department. She said Ms. Marshall was an iconic writer who had an important impact on the university and American literature.

“Her presence was felt within the department long after her time here,” Dr. Ingrassia said.

Born April 9, 1929, Valenza Pauline Burke was an immersive reader who loved old British novels from “Tom Jones” to “Great Expectations.” But she longed for books that included people more like herself, and so made an instant and deeper connection to the poetry in dialect of Paul Laurence Dunbar and later to writings by Ms. Hurston and Mr. Hughes, among others.

All along, she had been listening to her mother and various neighborhood women gather in the kitchen and expound in “free-wheeling, wide-ranging” style, voices she fictionalized in “Brown Girl, Brownstones” and other works.

“They were women in whom the need for self-expression was strong, and since language was the only vehicle readily available to them, they made of it an art form that — in keeping with the African tradition in which art and life are one — was an integral part of their lives,” she wrote in “The Poets of the Kitchen,” a 1983 essay.

Ms. Marshall graduated with Phi Beta Kappa honors from Brooklyn College. During much of the 1950s, she worked as a magazine researcher, traveling to Brazil and the West Indies, among other places. Since childhood she had been “harboring the dangerous thought” of becoming a writer, and in her spare time completed “Brown Girl, Brownstones,” published by Random House in 1959 after editor Hiram Haydn suggested she trim her 600-page “sumo-sized manuscript” to the “slender, impressive” novel buried within.

In her early 20s, she married Kenneth Marshall. They divorced when their son Evan was still young. She later married Nourry Menard, a Haitian businessman.