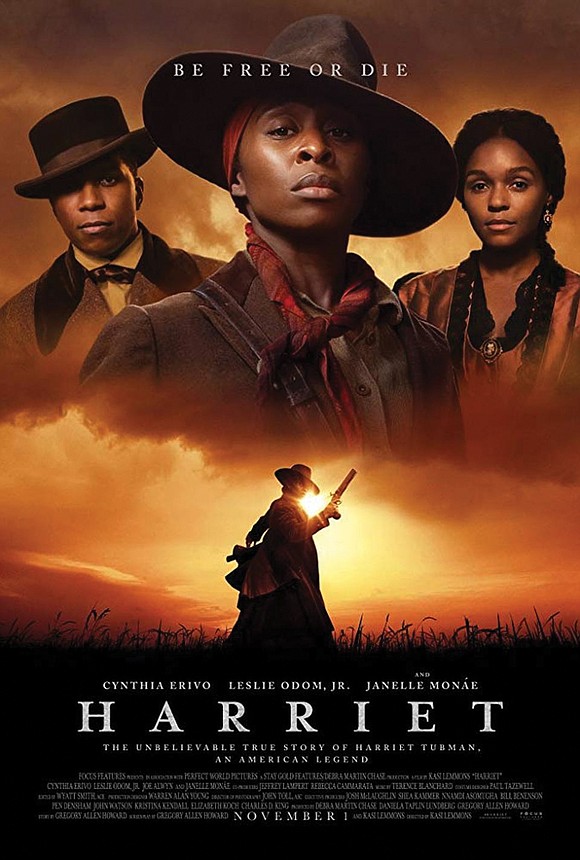

'Harriet' movie tells unvarnished story of need to 'live free or die'

Dr. Barbara Reynolds | 11/8/2019, 6 a.m.

For a nation built on truth, Harriet Tubman, an abolitionist, freedom fighter and ex-slave, should have the acclaim of a Paul Revere or Patrick Henry, whose courageous lines “Give me Liberty or Give me Death” guided the American Revolution.

Ms. Tubman, whose battle cry was to “live free or die,” guided another revolution. It was to end slavery, which changed the color, content and character of America today.

Through the release last weekend of the epic movie, “Harriet,” this revolutionary warrior, born into slavery in 1822 in Dorchester County, Md., has emerged from the back alley of history to take her rightful place as a larger than life action figure, a true American hero.

Unlike the heroes spun from Marvel comic strips or the Terminator franchise, Ms. Tubman is not fake, fantasy or make-believe, although her expansive accomplishments are more real than can be imagined.

Don’t think you are going to see the serene, sedate elderly Ms. Tubman of our textbooks. This is the Ms. Tubman of her youth, jaunting up rocky cliffs, jumping off bridges and even shooting a white slave owner with her pistol.

Through the skillful talent of British-born actress Cynthia Erivo, the film features Ms. Tubman not only as yesterday’s heroine, but also as a model of courage for today. Risking certain death if captured and often carrying a pistol in her waistband, she escaped from bondage on Maryland’s Eastern Shore and returned, often in disguise, to rescue more than 70 family members and others who were enslaved. She became a leader in the anti-slavery Underground Railroad and the Women’s Suffrage Movement in her long-standing struggle against systemic gender and racial inequality.

During the Civil War, she served as a nurse, scout and spy for the Union army and became the first woman to lead an armed expedition in the war, guiding a raid in June 1863 at Combahee Ferry in South Carolina that liberated more than 700 enslaved people.

Unfortunately, her heroism did not guard her from racism, as she initially was denied pension benefits that were granted to white soldiers.

In heart-aching detail, the movie does not sanitize the horror of slavery, nor does it gloss over the power of God in her life. Scenes of blood- soaked whips, scarred backs of enslaved men and women, screaming children torn from their families to be sold by white slave owners trading them as if they were dispensing sows from a pig pen — it’s all there.

But there is another story that shines through — one of black love, black loyalty and a determination of the enslaved to live free or die and the even- tual embrace of longawaited freedom. It’s all there.

In the movie, we see Ms. Tubman, after learning she is to be sold South, leave her family and the love of her life, her husband, John Tubman, to travel 100 miles alone to freedom in Philadelphia through the aid of the Underground Railroad.

Though the term “railroad” might prompt visions of nice cushy seats, this railroad Harriet traveled was a harsh pathway through snake-filled marshes, woods and deep rivers. Often, the flight of this woman, known to some as the “SheMoses,” was made even more treacherous as armed posses with baying hounds chased her in an attempt to collect the reward for her capture. But they never caught her. She once boasted that her railroad never ran off track and she never lost a passenger.

In the movie, she declared she had only the North Star to guide her, and we see her on her knees looking up to the heavens in deep communication with the God she depended upon to shield her from her enemies. My favorite scene is when the only choice for a band of fleeing enslaved people was to either turn back or cross a treacherous river. While her family cowered, frozen on the riverbank for fear of drowning, she lifted her pistol above her head, waded in the deep water and prayed aloud. She continued to walk on the riverbed, her head just above water. Then, as the depth receded, her feet touched dry land. Her family members jumped in and crossed the water as well.

The two-hour epic directed by Kasi Lemmons, who also wrote and directed “Eve’s Bayou,” sends the audience away with an inspirational song, “Stand Up,” co-written by Ms. Erivo and Joshuah Campbell, and sung by Ms. Erivo. The song sets just the right tone for “Harriet” enthusiasts to continue celebrating the freedom fighter. Former President Obama had selected Ms. Tubman to become the first person of color to be represented on any of the nation’s currency. She was to replace former President Andrew Jackson on the new $20 bill. Not surprisingly, in May 2019, the Trump administration delayed the launch.

Nevertheless, in Maryland, enthusiasts have other ways to celebrate Ms. Tubman. Painted on a wall of the Harriet Tubman Museum & Educational Center in Cambridge, Md., just a few miles from where Ms. Tubman grew up, is a 14-foot-by-28-foot mural featuring Ms. Tubman offering an outstretched hand. Not long ago, I placed my hand in her outstretched hand at the mural, thanking her for giving me the inspiration some 20 years ago to start a ministry at Greater Mt. Calvary Holy Church, under the leadership of Bishop Alfred Owens. Its purpose was to inspire people to have the courage and faith to break the chains of any addiction keeping them from living their best lives. In the ensuing years, scores have broken free, following in her footsteps of ending their personal bondage.

In March 2017, the Maryland Park Service and Maryland government opened the Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad State Park & Visitor Center in the heart of the Choptank River region where Ms. Tubman grew up. It’s a 17-acre facility that already has had nearly 200,000 visitors from all 50 states and more than 60 countries.

In her honor, the National Park Service also has established the Harriet Tubman National Historical Park in Auburn, N.Y.