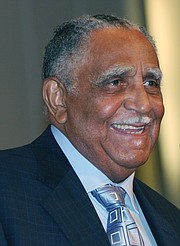

Rev. Joseph Lowery, head of SCLC and dean of civil rights veterans, dies at 98

Free Press staff report | , Free Press wire reports | 4/2/2020, 6 p.m.

ATLANTA - The Rev. Joseph E. Lowery fought to end segregation, lived to see the election of the country’s first African-American president and echoed the call for “justice to roll down like waters and righteousness like a mighty stream” in America.

For more than four decades after the death of his friend and civil rights icon, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., the fiery Alabama preacher was on the front line of the battle for equality, with an unforgettable delivery that rivaled Dr. King’s — and was often more unpredictable. Rev. Lowery had a knack for cutting to the core of the country’s conscience with commentary steeped in scripture, refusing to back down whether the audience was a Jim Crow racist or a U.S. president.

“We ask you to help us work for that day when black will not be asked to get in back; when brown can stick around; when yellow will be mellow; when the red man can get ahead, man; and when white will embrace what is right,” Rev. Lowery prayed at former President Obama’s inaugural benediction in 2009.

Rev. Lowery, 98, died Friday, March 27, 2020, at home in Atlanta surrounded by family members. He died from natural causes unrelated to the coronavirus out- break, the statement said.

“Tonight, the great Reverend Joseph E. Lowery transitioned from earth to eternity,” The King Center in Atlanta remembered Rev. Lowery in a tweet last Friday night. “He was a champion for civil rights, a challenger of injustice, a dear friend to the King family.”

Rev. Lowery, considered the dean of the civil rights veterans, co-founded the Southern Christian Leadership Conference with Dr. King in 1957 and served as its president and chief executive officer for two decades — restoring the organization’s financial stability and pressuring businesses not to trade with South Africa’s apartheid-era regime — before retiring in 1998.

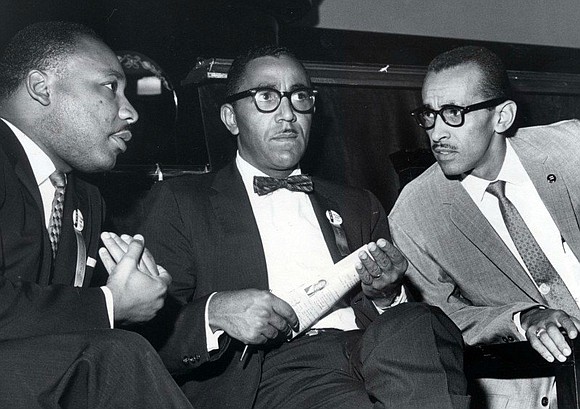

In his work with the SCLC, he came to Richmond, Hampton Roads and other parts of Virginia several times through the years, said Andrew Shannon, vice president of the Virginia State Unit of the SCLC. One iconic photo from September 1963 shows Rev. Lowery, then vice president of the SCLC, Dr. King and longtime King aide Dr. Wyatt Tee Walker conferring during a SCLC convention held at First African Baptist Church in Richmond.

Most recently, Rev. Lowery was the keynote speaker at the 2006 Andrew Shannon Gospel Music Celebration and Solidarity Luncheon held in Hampton.

“He was a great friend and freedom fighter,” Mr. Shannon said. “He fought for justice, freedom and equality for ev- erybody. He stood on principle even if it was unpopular.”

In one of many high-profile moments, Rev. Lowery drew a standing ovation at the 2006 funeral of Dr. King’s widow, Coretta Scott King, when he criticized the war in Iraq, saying, “For war, billions more, but no more for the poor.” The comment also drew head shakes from then-President George W. Bush and his wife, Laura Bush, who were seated behind Rev. Lowery on the pulpit.

In 2009, President Obama awarded Rev. Lowery the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the nation’s highest civilian honor.

Rev. Lowery’s involvement in civil rights grew out of his Christian faith.

Born in Huntsville, Ala., in 1921, Rev. Lowery grew up in a Methodist church where his great-grandfather, the Rev. Howard Echols, was the first black pastor. His father, a grocery store owner, often protested racism in the community.

After college, Rev. Lowery edited a newspaper and taught school in Birmingham, but the idea of becoming a minister “just kept gnawing and gnawing at me,” he said. After marrying Evelyn Gibson, a Methodist preacher’s daughter, he began his first pastorate in Birmingham in 1948.

Like Dr. King, Rev. Lowery juggled his civil rights work with ministry. He pastored United Methodist churches in Atlanta for decades and continued preaching long after retiring. He often preached that racial discrimination in housing, employment and health care was at odds with such fundamental Christian values as human worth and the brotherhood of man.

“I’ve never felt your ministry should be totally devoted to making a heavenly home. I thought it should also be devoted to making your home here heavenly,” he once said.

Rev. Lowery remained active in fighting issues such as war, poverty and racism long after retirement, and survived prostate cancer and throat surgery after he beat Jim Crow.

“We have lost a stalwart of the Civil Rights Movement, and I have lost a friend and mentor,” House Majority Whip James E. Clyburn of South Carolina said in a statement last Saturday. “His wit and candor inspired my generation to use civil disobedience to move the needle on ‘liberty and justice for all.’ It was his life’s work and his was a life well lived.”

Former President Clinton remembered walking with Rev. Lowery across the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Ala., on the 35th anniversary of Bloody Sunday. “Our country has lost a brave, visionary leader in the struggle for justice and a champion of its promise, still unrealized, of equality for all Americans. Throughout his long good life, Joe Lowery’s commitment to speaking truth to power never wavered, even in the hottest fires.”

Rev. Lowery’s wife, who worked alongside her husband of nearly 70 years and served as head of SCLC/WOMEN, died in 2013.

Rev. Lowery was pastor of the Warren Street Methodist Church in Mobile, Ala., in the 1950s when he met Dr. King, who then lived in Montgomery, Ala. Rev. Lowery’s meetings with Dr. King, the Rev. Ralph David Abernathy and other civil rights activists led to the SCLC’s formation in 1957. The group became a leading force in the civil rights struggle of the 1960s.

He became SCLC president in 1977 following the resignation of Rev. Abernathy, who had taken the job after Dr. King was assassinated in 1968. He took over an SCLC that was deeply in debt and losing members rapidly. He helped the organization survive and guided it on a new course that embraced more mainstream social and economic policies.

Mrs. King once said Rev. Lowery “has led more marches and been in the trenches more than anyone since Martin.”

He was arrested in 1983 in North Carolina for protesting the dumping of toxic wastes in a predominantly black county and in 1984 in Washington while demonstrating against apartheid in South Africa.

He recalled a 1979 confrontation in Decatur, Ala., when he and others were protesting the case of a mentally disabled black man charged with rape. He recalled that bullets whizzed inches above their heads and a group of Klan members confronted them.

In the mid-1980s, he led a boycott that persuaded the Winn-Dixie grocery chain to stop selling South African canned fruit and frozen fish when that nation was in the grip of apartheid.

He also continued to urge black people to exercise their hard-won rights by registering to vote.

“Black people need to understand that the right to vote was not a gift of our political system but came as a result of blood, sweat and tears,” he said in 1985.

In a 1998 interview, Rev. Lowery said he was optimistic that true racial equality would one day be achieved.

“I believe in the final triumph of righteousness,” he said. “The Bible says weeping may endure for a night, but joy cometh in the morning.”

A member of Alpha Phi Alpha Fraternity, Rev. Lowery is survived by his three daughters, Yvonne Kennedy, Karen Lowery and Cheryl Lowery.

While plans are underway for a private family service in alignment with public health guidelines on social distancing amid the pandemic, the family said a public memorial will be held in late summer or early fall.