Black clergy memorialize the dead; ask gov’t. to address disparities

Adelle M. Banks/Religion News Service | 4/23/2020, 6 p.m.

The Rev. Frank Williams has been so busy leading two black churches in the New York borough of the Bronx that he hadn’t really considered the full extent of COVID-19’s impact on his congregation, his family and his community.

But when asked, the Southern Baptist pastor of two churches, each with more than 200 members, realized after four weeks the list was long:

The Saturday before Easter, a beloved deacon — a decades-long friend who had been the property manager, the men’s ministry leader and the person who ran the van ministry picking up seniors for Bronx Baptist Church — died from complications related to COVID-19.

Rev. Williams’ wife, a hospital residency coordinator, and his three children, all under the age of 12, have recovered from COVID-19 and he preached his first online sermons from the Psalms while quarantined.

The 47-year-old pastor helped the staff of Wake-Eden Community Baptist Church’s elementary school shift to remote learning and, as the need for food in the nearby community increased, worked to provide families with food that previously would have been prepared for their children at a church day care.

“The impact is very real for us, not just here in New York, but very real for us as a congregation,” said Rev. Williams, a St. Kitts native whose churches include black Americans and immigrants from Africa and the Caribbean.

Across the country, black clergy say the coronavirus is touching — and sometimes taking — the faithful who, until a month ago, were accustomed to meeting weekly in their pews. Some are mourning losses in the highest echelons of their denomination. Others are counting the dead, sick and unemployed.

And some African-American pastors are joining forces to demand the Trump administration and congressional leaders take action, ranging from setting up testing sites in black and poor communities to providing masks to low-wage essential workers, prisoners and people living in homeless shelters.

The federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recently released a March report that showed 33 percent of hospitalized patients in a 14-state study were African-American; comparatively, African-Americans constitute 13 percent of the U.S. population.

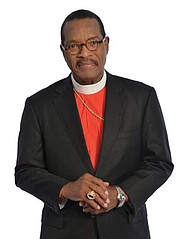

At least one historic black denomination has started a preliminary tally of the toll of COVID-19. Bishop Gregory Ingram leads the African Methodist Episcopal Church’s First Episcopal District which includes the hard-hit areas of New York, and asked presiding elders within it to report what they knew about members’ health and economic statuses. An April 15 report shows that throughout the district, which also includes churches in states such as New Jersey and Delaware, 48 members have died, 258 have been infected and 1,913 have become unemployed as a result of COVID-19.

“I had one church that lost three members in one day,” Bishop Ingram said, referring to a congregation in Freeport, Long Island.

Another of the deceased from the AME denomination is Yonkers Pastor Scott Elijah, who died in late March. He was remembered not only by his small church but by Local 100 of the Transport Workers Union, which recalled his work with NYC Transit in a “Lost to Coronavirus” listing: “The entire Track Division is in mourning.”

Bishop Ingram and his wife, the Rev. Jessica Ingram, have been praying on 6 a.m. daily calls with members of their district and following up by phone with church members who have lost loved ones to COVID-19.

“This is new territory for us,” said Rev. Ingram, who as the episcopal supervisor for the district has been co-hosting Zoom meetings with leaders among the young adults, laity and pastors in the district. The training and study sessions have centered on topics ranging from the “new landscape of the church” to health disparities. “And we don’t have answers, so basically I just express my prayers for them and listen and let them know that we are here for them,” she said.

The Church of God in Christ, another historic black denomination, reportedly has lost close to a dozen of its bishops and other leaders to COVID-19, including Bishop Phillip Aquilla Brooks II, who was the Michigan-based first assistant presiding bishop.

“The loss of such a respected visionary leader cannot be verbally expressed,” said COGIC Presiding Bishop Charles Blake in a video announcement that did not specify the cause of death for Bishop Brooks or the others. “I know that the death of Michigan Bishop Brooks, Nathaniel Wells and so many others has caused great concern and great pain throughout the church, concern for our leaders and concern for the future of the church.”

After noting that he and his family were well, Bishop Blake spoke of divine pledges and the need to lean on God.

“At this challenging time, I want you to remember that God has promised that the gates of hell shall not prevail against his church,” he said in the announcement on the homepage of the COGIC website. “And I’m absolutely confident that God is going to bring us through this tough time together. We as people of faith must look to God and to the word of God as we have in challenging times past for hope and for encouragement.”

At a video news conference hosted April 15 by the Samuel DeWitt Proctor Conference and Repairers of the Breach, black clergy called on leaders at the White House and in Congress to provide more resources to African-Americans and to focus more on humanity than the economy.

“Black people are more likely to be essential workers, keeping us safe and fed,” said the Rev. William J. Barber II of North Carolina, president of Repairers of the Breach. “But these are the very people the stimulus bill did not provide (with) the essentials of health care, living wages or even guarantee that no water would be shut off, while corporations in less than three weeks got $2.5 trillion.”

Clergy on the call spoke of praying over the phone with health care workers in their congregations who lack protective equipment and people who can’t pay their rent.

“There is no sheltering in place when there is no shelter,” said Bishop Yvette Flunder, a San Francisco preacher af- filiated with the Metropolitan Community Churches and who oversees a ministry site that provides food, medical and housing case management services.

The Rev. Traci Blackmon, a justice executive minister for the United Church of Christ and leader of a church north of St. Louis, said her congregation includes bus drivers, grocery workers and mail carriers. She said five of about 80 congregants tested positive for COVID-19 and three went to the hospital multiple times before they could get tested, thus exposing their households in the meantime.

“I pastor people who are now seeking food for their children and for their families because those food services have had to be suspended because of the deaths of two bus drivers who died from COVID-19,” Rev. Blackmon said.

The Rev. Frederick Haynes III, pastor of Friendship-West Baptist Church in Dallas, opened the videoconference with an “appeal to those in power on behalf of communities in pain and in grief.” In a separate interview, he noted that black community leaders who have been concerned about environmental justice and health disparities now will have to see what more the black church can do.

“There are those of us who have been fighting for that and now we are upgrading our fight because we are seeing that this country has proven that it does not have a desire to protect us,” he said.

News reports have indicated other examples of how the coronavirus has ended the lives of longtime churchgoers and clergy from Louisiana to Maryland to New York City’s Harlem. A Pentecostal pastor in Virginia, Bishop Gerald O. Glenn of New Deliverance Evangelistic Church outside Richmond, who claimed “God is larger” than the coronavirus, succumbed to it, his church announced. His widow, two daughters and son-in-law are recovering from the disease.

Clergy tasked with memorializing people who have died, often unexpectedly, say the coronavirus has prompted uncharacteristic changes in funeral and burial traditions.

The Rev. Adolphus Lacey, pastor of Bethany Baptist Church in Brooklyn, said last week that his 900-member congregation has had three confirmed COVID-19 deaths. He officiated at two funerals on one day — one at a Brooklyn funeral home and one an hour-and-45-minute drive away in New Jersey.

Though familiar with the rites of death, Rev. Lacey said wearing masks, gloves and keeping socially distant has made the moments of farewell even more difficult.

One funeral, for a popular usher, was carried out on Zoom and so many wanted to participate, some never got past the virtual waiting room.

“The sad part, I said, he was at everybody else’s funeral. But when it came to his funeral, nobody could be there but just his family,” said Rev. Lacey, whose church is affiliated with the Progressive National Baptist Convention Inc. and the National Baptist Convention U.S.A. Inc.

From his New York borough north of Rev. Lacey’s, Rev. Williams spoke of his longtime faith helping him cope with the sadness and hang on to hope.

“There are always people who experience loss and that’s the reality of grief,” Rev. Williams said. “We are experiencing that in the loss of our deacon but we are still praying for God’s preservation. And that really comes from Psalm 121, where it says ‘I will preserve you from all evil. I will preserve your soul.’ ”