Home health workers often overlooked in state COVID-19 protection efforts

Jeremy M. Lazarus | 6/25/2020, 6 p.m.

Ever since the COVID-19 emergency was declared in March, the state has pushed a well-publicized effort to get masks, gowns and other protective gear for doctors, nurses and other health care workers in hospitals and nursing homes.

But three months into the pandemic, the state finally has begun to focus on providing protection gear to a little-noticed group of front line health workers — the aides providing care to thousands of elderly and disabled people in their homes.

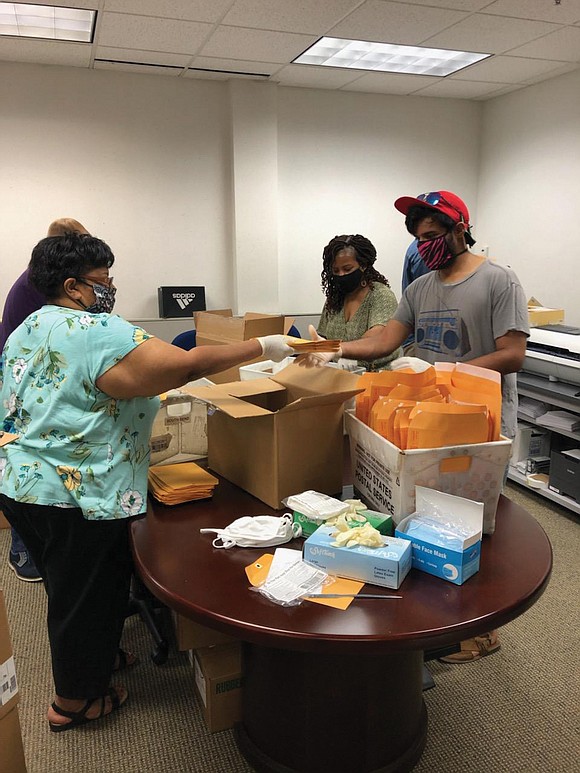

On Wednesday, 30,000 masks were being assembled in packages to be shipped to personal care workers, according to Christina Nuckols, spokeswoman for the state Department of Medical Assistance Services, which runs the state’s Medicaid program.

“Given the barriers that exist, this has been a unique process to secure and distribute personal protection equipment to our personal care workers. But we have worked hard to accomplish this important goal for these essential home and community- based providers,” said Dr. Vanessa Walker Harris, deputy state secretary for health and human resources.

The move is aimed at ending the neglect of often overlooked personal care and certified nursing assistants who almost daily care for at least 20,000 people across the state.

Thomasine Wilson, 60, of Richmond, executive committee chair of a local union for home health care workers, said the work of bathing, grooming, serving light meals and helping people go to the bathroom requires close physical proximity, rather than the 6 feet social distancing under general COVID-19 guidelines.

“Many of us travel by bus, and we bring what we pick up into the home,” said Ms. Wilson, a longtime advocate for the workers. “We need the protection for our clients and for ourselves so we don’t bring the virus home to our families.”

Most of the workers serve people who receive care through Medicaid. And despite the critical services they provide, the workers are among the most overlooked element in health care, Ms. Wilson said.

Currently, the state limits pay for the largely female workforce to $8 an hour and lists them as contract workers, which makes them ineligible for overtime. The state also bars clients from paying them extra.

Home care workers also are not eligible for paid sick leave or vacation pay, Ms. Wilson said.

“If we don’t work, we don’t get paid,” she said, “and the pay is not a living wage, which is what we need. The time with any one client is limited to a certain number of hours, and often we have to find multiple clients to work with in order to get close to 40 hours a week.”

The pandemic has been devastating for home health care work- ers, Ms. Wilson said. “They face a difficult choice: Stay home without income and live, or go to work, get sick and die.”

“Our union has been pressing for the state to provide PPE for home care workers,” said David Broder, president of Service Employees International Union’s Virginia 512 unit that includes the home health care employees.

He said the state’s failure to prioritize PPE for home health care workers — a majority of whom are African-American — reflects many of the embedded wrongs that leave women and people of color at the bottom in such matters.

He said the SEIU has sought to fill in by buying masks for members, but it falls short of what the state can do with the federal funding it has received.

“Our members are making $15,000 to $20,000 a year, with none of the perks that other health care workers enjoy,” he said. “They even have to pay for their own transportation. They should have been a priority. But, once again, they were not.”

Mr. Broder noted that without such home health care work- ers, the Medicaid program would be paying large sums to care for the clients in nursing homes and other institutions. “Our members are saving the state huge amounts of money, but there has been little change in their conditions.”

He said there was some movement in a recent session of the General Assembly, which passed protections for domestic workers and included home health care workers. The home health care workers also are eligible for the increase in the state’s minimum wage that is to be effective next year.

“Home care workers need and should get a living wage,” Mr. Broder said. “They provide incredibly important services that enable people to stay in their homes and familiar surroundings. They deserve better.”