Enrichmond unveils $18.6M master plan for Evergreen Cemetery

Jeremy M. Lazarus | 3/6/2020, 6 a.m.

Historic Evergreen Cemetery would be transformed into an outdoor college of African-American history and culture if the nonprofit that now owns the burial ground in the city’s East End can pull it off.

The city-created Enrichmond Foundation released an ambitious and expensive plan to turn the once proud but long- neglected 59-acre burial ground for at least 20,000 people into a place that would “inspire present and future generations to honor the nation’s African- American inheritance” through programming, education and preservation.

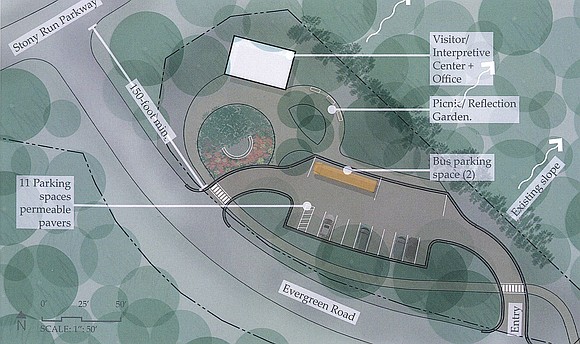

Among other things, the plan calls for building a visitor center on the grounds that border East Richmond Road and Stoney Run Parkway, developing a grave record system, installing interpretive signage, creating a memorial garden and highlighting the areas where the most famous people are buried, such as Richmond businesswoman Maggie L. Walker, the first African-American woman to charter and operate a bank.

The preliminary estimate to carry out the vision: $18.6 million, none of which is currently available, according to the foundation.

The vision is contained in a 170-page master plan released Saturday by Enrichmond. Viola O. Baskerville, who led the five-member volunteer team that worked with Atlanta-based consultants Pond & Co., called the plans the kind that “will stir the soul. They are bold. They are audacious.

“Let us realize the vision. The ancestors have waited way too long,” the former Richmond city councilwoman, General Assembly member and state secretary of administration told about 30 people who attended the plan’s unveiling at the Maggie L. Walker National Historic Site in Jackson Ward.

Mayor Levar M. Stoney joined in cheering on planning for Evergreen’s future, but has yet to get the city more involved. The city, for example, continues to maintain ownership of two segregated burial grounds that are no longer used, Colored Paupers and Oakwood Colored Paupers. Those cemeteries abut Evergreen, but the property has not been turned over to Enrichmond to become part of the vision. Like much of Evergreen, the grounds of the two cemeteries are largely overgrown.

John Sydnor, executive director of the Enrichmond Foundation, which was established in 1990 to support nonprofits that work on recreation, cultural and environmental issues, views the plan as a blueprint for Evergreen’s future.

Enrichmond acquired Evergreen Cemetery in 2017 from the family of Isaiah Entzminger with help from a Virginia Outdoors Foundation grant of $400,000. People were buried in Evergreen until a few years ago.

Still, the master plan is mostly a paper step toward reclaiming the cemetery that has relied mostly on the drive of volunteers such as John Shuck, Veronica Davis, John Bell, Marvin Harris, Boy Scouts, Girl Scouts and thousands of others.

Evergreen dates to 1891 when African-American civic leaders sought to create their own version of the private, white Hollywood Cemetery in Richmond at a time when the city’s burial ground for African-Americans primarily was for those who could not afford burial. However, Evergreen did not add a fee for perpetual care, which was not required. Over time, the gravesites were overgrown with weeds, shrubs and trees.

In addition to Mrs. Walker, the prominent figures buried in Evergreen include crusading editor, banker and African-American political leader John Mitchell Jr. and Dr. Sarah Garland Boyd Jones, the state’s first female physician and founder of the area’s first African-American hospital.

Despite the many pages in the plan, it is still incomplete. Notably, there is no mention of the separate and equally historic East End Cemetery, a private, African-American cemetery of 16 acre that abuts Evergreen’s west side and which Enrichmond added to its holdings last year. Currently, the entry to Evergreen comes through East End Cemetery.

Opened around 1896, East End Cemetery includes an estimated 13,000 African-American grave sites, including those of educator and civic and political leader Rosa L. Dixon Bowser and of physician and banker Dr. Richard F. Tancil.

Mr. Shuck and volunteers Brian Palmer and Erin Holloway have led untold volunteers to clear the overgrowth at East End. As a result, Mr. Shuck said, about 80 percent of East End is now cleared.

At Evergreen, more than half of the property, including the roads and paths, still have to be cleared, according to Enrichmond. Volunteers and staff Enrichmond has hired have cleared about 22 acres, or 36 percent of the total acreage, and opened up five of the 11 miles of roads and paths that crisscross Evergreen, according to information in the master plan.

Mrs. Baskerville remains optimistic that funds will be raised so that the Evergreen master plan will not sit on the shelf.

“The money is out there,” she said. “We just need to tap into it.”