Black people and COVID-19, by Sa’ad El-Amin

5/14/2020, 6 p.m.

As the United States is trying to reopen after a nearly total shutdown caused by COVID-19, one of the major questions is whether it is too early to reopen and, by doing so, whether there will be a second round of infections and deaths.

There are two important lessons learned for people of African descent regarding the COVID-19 pandemic.

First, we are disproportionately and negatively impacted by this virus because we are the majority of those infected and killed by this virus.

Second, the disparate results from COVID-19 reveal something that we all know is true i.e., we suffer disproportionately from diseases such as diabetes, asthma, heart disease and respiratory issues, all of which COVID-19 exploits.

I find it disheartening that there have been no calls from our political leadership to address this disparate impact. To date, we have not seen or heard a demand for programs or initiatives that would substantially reduce our morbidity so that the truism, “White folks get a cold, black folks get pneumonia and die,” will become the exception rather than the rule.

Disproportionality has been the bane of our existence, beginning with how we were treated in Article I, Section 2 of the U.S. Constitution of 1787. That is the three-fifths clause, which declared that, for purposes of representation in Congress, an enslaved black person would be counted as three-fifths of a person, while a state’s white inhabitant would be counted as a whole person.

It does not help that as COVID-19 plays out its cruel and unusual treatment of human beings, far too many black people refuse to wear masks and practice social distancing, manifesting that they are not serious about dealing with COVID-19.

One would think that given our significant disproportionality in being infected and dying from this virus, black people would be twice as alert and on guard. Unfortunately, like other important matters in our quality-of-life issues, we seem to act as if it is someone else’s responsibility rather than ours to protect ourselves from the cruelty of disproportionality.

It appears that we have not learned from our history in America that disproportionality is the status quo, which we more often than not buy into rather than resist. Have we forgotten being last hired and the first fired; that we are four times as likely to be killed by a black person; that we are many times more likely to be convicted of serious felony offenses; that our wages and earnings are significantly less than white people, although we’re doing the same job; or our life expectancy is at least 10 years or more shorter.

Despite our history being rife with such disparities, we more often than not conduct ourselves in a manner that invites and encourages others to continue these disparities rather than curtail them.

For example, we insist that we be recognized and treated like black lives matter. However, we treat each other and even ourselves like black lives do not matter, which means that we are engaged in rhetorical hypocrisy by asking others to do what we fail to do. We cannot demand that others treat us better than we treat ourselves. That is one of the main reasons that many of our demands for equal treatment are by and large ignored.

We should always remember the words of U.S. Supreme Court Justice Roger B. Taney, which undergird the Dred Scott decision of 1857, that enslaved persons were not citizens of the United States and had no rights to sue in federal courts. Justice Taney declared that black people have no rights that white people, are required to recognize, respect, protect or defend. I know of no event or events since the Dred Scott decision that nullify Justice Taney’s words and thoughts.

I do remember the words and thoughts of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. as he stood on the steps of the State Capitol in Montgomery, Ala., on March 25, 1965, in his presentation “Our God Is Marching On!”

Dr. King ended his speech by asking, “How long will prejudice blind the visions of men, darken their understanding and drive bright-eyed wisdom from her sacred throne? When will wounded justice, lying prostrate on the streets of Selma and Birmingham and communi- ties all over the South, be lifted from this dust of shame to reign supreme among the children of men? When will the radiant star of hope be plunged against the nocturnal bosom of this lonely night, plucked from weary souls with chains of fear and the manacles of death? How long will justice be crucified, and truth bear it?”

“I come to say ... however difficult the moment, however frustrating the hour ... truth crushed to earth will rise again ... no lie can live forever ... [and] you shall reap what you sow ... How long? Not long, because the arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice.”

However, Dr. King did not factor in black folk engaging in self victimization by failing to protect ourselves from hurt, harm and danger and waiting for someone else to cause the arc of the moral universe to bend toward justice.

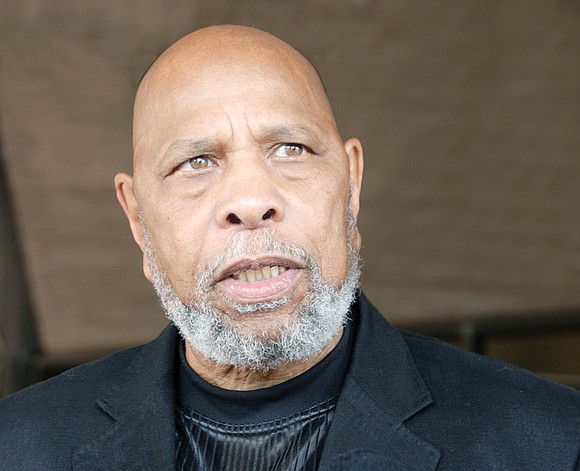

The writer, a graduate of Yale Law School, is a former member of Richmond City Council and president of Strategic and Litigation Consultants.