High prescription drug prices hitting hardest in communities of color

Hazel Trice Edney/Hazel Trice Edney News Wire | 11/5/2020, 6 p.m.

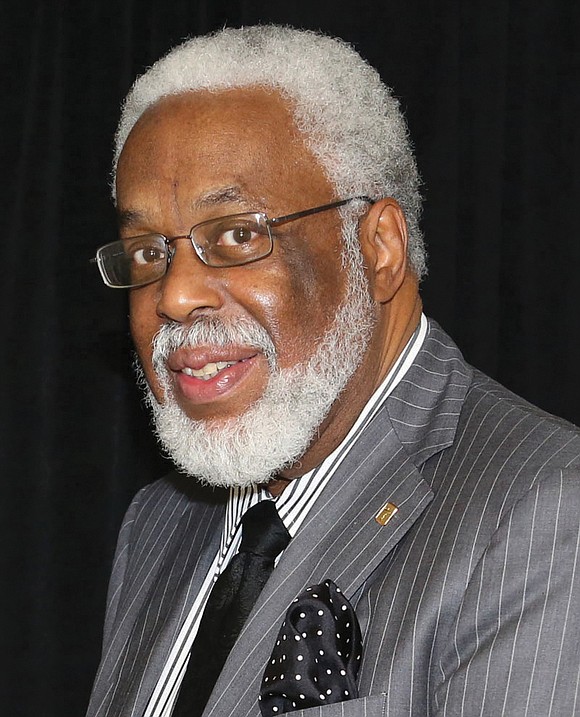

Dr. Leonard L. Edloe, a pharmacist of 50 years and pastor of a predominately Black church in Middlesex County, knows well the personal and professional sides of heart disease, stroke and diabetes. He also knows the astronomical costs of prescription medications and the related financial struggles.

His late father opened the first of their four, family-owned pharmacies in 1948. And he was only 65 when he came home from work one day, sat down, had a sandwich and a beer and then died of a massive heart attack.

It was a major emotional blow for Dr. Edloe to lose his father and mentor that way. And then Dr. Edloe’s sister died at 60 and his brother at 54 — also both of heart attacks.

“I had to get out,” Dr. Edloe said, adding he closed the businesses. He reflected on his now determined self-care through exercise and healthy eating. “I’m 73 now.”

For decades, Dr. Edloe has been a prominent household name in Richmond, where his father’s first pharmacy was established. Since his family was upper middle class, he acknowledged they had no problem paying for prescription medication. But given his father’s legacy and his own community service through his profession and dedication to help people in need, he is known for being on the cutting edge of the struggle to establish health equity. That includes exploring ways to make prescription drugs more affordable and accessible to all.

“The pricing has gone through the roof,” Dr. Edloe said in an interview. “I mean, insulin — a month’s supply for some people — is $600.”

That’s $7,200 a year.

“Even the generic pricing has gone up,” he points out. “That has become worse because so many of the drugs are imported. Seventy-five percent of the drugs in the United States have an ingredient that’s made in China, India or Germany.”

Dr. Edloe explained that because “there’s no control over pricing in the United States, they can basically charge what they want to, whereas in other countries, the government decides.”

As a former longtime member of Medicaid HMO Virginia Premier Health Plan’s board, Dr. Edloe pointed out that the drug used to treat Hepatitis C costs $1,000 a pill. But in Egypt, it is $1 a pill.

Dr. Edloe has expressed his concerns about drug prices through the years in his various leadership roles, including as chair of the Virginia Heart Association for the Mid-Atlantic Region, president of the American Pharmacists Association Foundation and board member of the Virginia Commonwealth University Health Systems Authority.

“My blood pressure medicine for myself has tripled in price. I was paying $15 for three months. Now it’s $45,” he said. “Fortunately, that’s with my insurance.”

For people who lack health insurance, medicine for hypertension can cost upward of $300 to $600 a year, which can be difficult to manage financially along with paying for other medications and bills. “So, it’s real serious,” Dr. Edloe said.

Community health workers and researchers around the country have long recognized the increasing costs of prescription drugs and the difficult choices some people must make to afford them.

An article in Harvard Medical School’s Harvard Health Publishing, titled “Millions of Adults Skip Medications Due to Their High Costs,” highlights findings from a national survey conducted by the Center for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Center for Health Statistics:

• Eight percent of adult Americans don’t take their medicines as prescribed because they cannot afford them.

• Among adults under 65, 6 percent who had private insurance still skipped medicines to save money.

• 10 percent of people who rely on Medicaid skipped their medicines.

• Of those who are not insured, 14 percent skipped their medications because of cost.

• Among the nation’s poorest adults — those with incomes well below the federal poverty level — nearly 14 percent “did not take medications as prescribed to save money.”

Those statistics get even worse when exploring prescription drug affordability in the Black community. According to the National Center for Biotechnology Information, a division of the National Institute of Health, “elderly Black Medicare beneficiaries are more than twice as likely as white beneficiaries to not have supplemental insurance and to not fill prescriptions because they cannot afford them.”

Likewise, an AARP survey of 1,218 African-American voters last year found that more than three in five (62 percent) said “prices of prescription drugs are unreasonable” and nearly half (46 percent) said they did not fill a prescription provided by their doctor mainly because of cost.

The inability to pay for prescription drugs — even for those under the age of 65 — has significantly impacted Black people, Latinos and other people of color due to economic disparities.

“Though the Affordable Care Act reduced the number of uninsured Americans, over 28 million remain without insurance,” said PublicHealthPost.org. “More than half (55 percent) of uninsured Americans under the age of 65 are people of color. For those with no insurance, paying retail prices for medications is often financially impossible.”

This is no secret to those who have been working in the trenches on critical health care issues daily for years.

Ruth Perot, executive director and chief executive officer of the Summit Health Institute for Research and Education, serves the 92 percent Black and largely low-income families of Washington, D.C.’s 6th, 7th and 8th Wards. She has been working on grassroots health equity issues in communities of color for more than 23 years.

“I am certainly aware of the extent to which folks have to make that choice between the cost of a prescription and the other commitments that they have — whether it’s rent or whether it’s food on the table or something related to the education for their children,” Ms. Perot said. “The cost of prescription drugs has always been out of control. It’s been a major profit-motive driven industry. That’s been true for some time.

“And so, whatever we see at the national level from a policy perspective still hasn’t addressed the fundamental issue that drug prescriptions cost too much ... I don’t think the federal government has ever used its power as the principle buyer of drugs to get those prices down. It has been a persistent problem for many, many, many years if not decades,” she said.

Dr. Edloe, whose pharmacies were located mostly in predominately Black communities, agrees. In addition to his medical career, he also interfaces with the community as pastor of New Hope Fellowship Church in Hartfield, Va. As he works on his own health, he passes along health lessons to his congregation and is intimately familiar with their struggles to pay for prescription drugs.

Currently working with two groups involving health disparities and pharmaceuticals, he said he believes the answer to achieve equity will ultimately be “some form of universal health care.”

But there also must be a culture change, he said, “because a lot of health care providers still are not trained and the materials are still not designed for diverse communities.”

“It’s all about getting equity — not equality — but equity in health care because there’s a big difference,” Dr. Edloe continued. “If everybody stands beside the fence and the fence is 6 feet and you’re 6 feet 5 inches tall, you can see over it, but other people can’t. Equity means you might have to give them a stool to see.”