Another case of inequity?

2 people rob the same SunTrust Bank but sentences different as black and white

Jeremy M. Lazarus | 10/15/2020, 6 p.m.

Two people robbed the same SunTrust Bank branch in Hanover County four years apart.

Both were caught, both were convicted. But their sentences offer a prime example of the racial disparities for which the court system is notorious, as numerous research studies have documented.

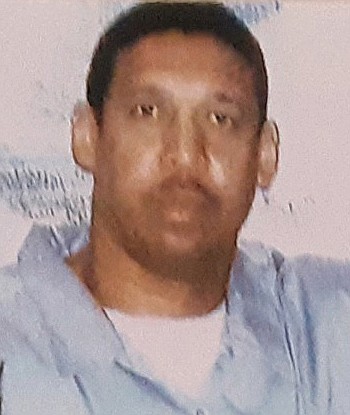

One of the robbers is an African-American, Henry C. Brailey, who participated in robbing the branch on Beaverdam School Road in 2006.

His sentence: 93 years in state prison, with 53 years suspended. The judge in his case sent him to prison for 40 years.

The second robber is a white woman, Tori K. Pollard, who robbed the same branch in 2010.

Her sentence: 20 years in prison, with 15 years and three months suspended.

The judge in her case sent her to prison for three years and nine months, even though he was aware that Ms. Pollard had pleaded guilty to robbing a different bank in Spotsylvania County.

Ms. Pollard has completed her sentence, while Mr. Brailey remains behind bars.

Under current state law, he must serve 85 percent of his sentence, or 34 years, before he possibly could be released based on his record in prison. He was 36 when he was convicted and is now 50. He will be 70 before he can be considered for release if nothing changes.

A former truck driver with a spotless record since going inside, Mr. Brailey is an inmate at the Greensville Correctional Center in Jarratt. He knows he got hammered by now retired Hanover Circuit Court Judge Horace A. Revercomb III.

In a letter to the Free Press, Mr. Brailey wrote that he has since learned that the state’s sentencing guidelines, if followed, would have recommended a sentence of six to 11 years.

According to the court transcript, Judge Revercomb found the guideline’s sentencing range inadequate after reviewing Mr. Brailey’s past history of convictions and labeling him a career criminal.

“When I tell other inmates how much time I received, they tell me they know someone who robbed two banks and got 21 years,” Mr. Brailey wrote in his letter.

He stated he also has met several inmates who were convicted of robberies and were sentenced to 12 years or less, despite having records involving more violence.

And he noted that one of his co-defendants, a former girlfriend, received only six years, while another co-defendant was acquitted.

With his appeals exhausted, Mr. Brailey is like many inmates whose only hope of shorter time is through intervention from the governor, the single state official with authority to commute prison terms.

Mr. Brailey’s mother, retired schoolteacher Josephine Starks, has been campaigning almost nonstop for four years to have her son’s sentence commuted by the governor.

State senators and delegates and even a member of Congress have taken an interest in the case, as have others who know Mrs. Starks and her son. They have provided letters of recommendation supporting early release for Mr. Brailey. So have several Department of Corrections employees who have met and worked with him.

Mr. Brailey has tried to demonstrate he would do well if released from prison. He has taken multiple courses in prison, participated in mental health counseling and worked in housekeeping.

Still, a sentence commutation remains a long shot. Petitions for clemency are piled high in the office of the state Secretary of the Commonwealth, the designated office to review petitions for clemency and pardons and make recommendations to the governor.

That office relies on a small team of around seven investigators at the Virginia Parole Board to do the actual investigative work. Those investigators are swamped with hundreds of cases.

According to some familiar with the process, petitions can stay on a desk for at least two years and often longer.

Mr. Brailey filed his first petition for clemency in 2016 while former Gov. Terry McAuliffe was in office.

Sa’ad El-Amin, a former Richmond City Council member who now runs an advocacy office, filed an updated petition in recent months after learning about Mr. Brailey’s sentence from his mother.

“I was outraged, and I remain outraged that this man is still in prison,” Mr. El-Amin said. “In my 50 years of advocacy, this is the most egregious disparate sentence that I have ever known about.”

Mr. El-Amin said he is even more outraged after finding out about the far more lenient sentence Ms. Pollard received compared to Mr. Brailey.

He has posted information on Mr. Brailey on his website, 1619inc.org, in hopes of garnering public interest.

He would love to see the Black Lives Matter or the Virginia Legislative Black Caucus take up the cause of Mr. Brailey. While individual caucus members, such as Richmond state Sen. Jennifer L. McClellan, has been engaged, the entire caucus has not put the matter on its agenda or issued any statements calling out the inaction on the case.

“I know he did wrong. So does he,” Mrs. Starks said of her son. “But everyone deserves another chance to prove that they have changed.”