Chadwick Boseman, who brought icons to life on the silver screen, dies at 43

Free Press wire reports | 9/3/2020, 6 p.m.

Wakanda forever!

Those words have gone viral on social media since the announcement last Friday that Chadwick Boseman, who starred in the blockbuster superhero Marvel film “Black Panther,” shockingly died at the age of 43 in his home in Los Angeles after a private, four-year battle with colon cancer.

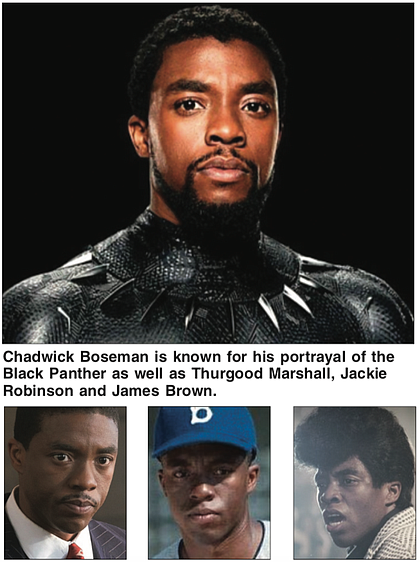

Mr. Boseman was an important pillar in the African-American entertainment world who humanized several Black historical trailblazers in his roles — including color-line breaking baseball star Jackie Robinson, legendary singer James Brown and the first African- American U.S. Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall. His family said he endured “countless surgeries and chemotherapy” while portraying King T’Challa of Wakanda in the Oscar-nominated “Black Panther,” a film that proved a person of color could lead a successful superhero film.

“For him to pass at this time when we are disproportionately affected by COVID and have all of these attacks by law enforcement, and him being the symbol bringing us to Wakanda, it’s just a blow,” said the Rev. Al Sharpton, founder and head of the National Action Network. “To hear that our superhero who projected a positive light was now gone, it was a gut blow.”

Mr. Boseman was elevated to a stage that many Black actors don’t get the chance to occupy, said Los Angeles Lakers star LeBron James. And his ability to be “transcendent” on that stage brought a comic book character to life for many in the Black community.

“Even though we knew that it was like a fictional story, it actually felt real. It actually felt like we finally had our Black superhero and nobody could touch us. So to lose that, it’s sad in our community,” Mr. James said, lamenting on the loss of the Black Panther and the “Black Mamba” — basketball superstar Kobe Bryant — in the same year.

In a tragically brief but historically sweeping life as an actor, Mr. Boseman played men of public life and private pain. Before Friday, few knew that he, too, was bearing such a burden. That has only magnified his accomplishment, bringing him closer to the great figures whose shoes he wore on film. He played men who advanced a people’s progress, a trail he helped blaze himself. He played icons, and died one, too.

“There’s a lot to learn from Jackie Robinson. There’s a lot to learn from James Brown. There’s a lot to learn from Thurgood Marshall,” Mr. Boseman said in an interview with The Associated Press two and a half years ago. “I would like to say that some of those qualities have infused themselves into me at this point.”

Mr. Boseman started out as a playwright. He was raised in the manufacturing town of Anderson, S.C., the youngest of three boys. As a junior in high school, he wrote and staged a play inspired by the shooting death of a basketball teammate. Before he was a Hollywood star, he penned numerous hip-hop-infused plays — “Hieroglyphic Graffiti,” “Rhyme Deferred,” “Deep Azure” — and directed others. In New York, he performed with the National Shakespeare Company.

He compared his alma mater, Howard University, to his own personal Wakanda.

“If you have a blanketed idea of what it means to be of African descent and you go to Howard University, you’re meeting people from all over the diaspora — from the Caribbean, any country in Africa, in Europe,” Mr. Boseman said. “So you’re seeing people from all walks of life that look like you but they sound different.”

It wasn’t until he was in his mid-30s, after a handful of brief television appearances, that he landed his first leading role as Jackie Robinson in “42.” He was, from the start, a self-evident movie star with a rare, effortless charisma. Rachel Robinson, the baseball Hall of Famer’s widow, said it was like seeing her husband again.

Mr. Boseman died on the day that Major League Baseball was celebrating Jackie Robinson Day. “His transcendent performance in “42” will stand the test of time and serve as a powerful vehicle to tell Jackie’s story to audiences for generations to come,” the league wrote in a tweet.

Since the news of Mr. Boseman’s death, the story of how Denzel Washington paid for Boseman and other Howard students to attend a summer theater program at the University of Oxford has been much retold. It’s especially fitting because it, as if by fate, links Mr. Boseman with Mr. Washington. Like his long-ago benefactor, Mr. Boseman exuded strength and self-possession. When he played Mr. Robinson and James Brown in “Get on Up” and Justice Marshall in “Marshall,” Mr. Boseman’s power wasn’t asked for or worked up to. It was innate. It was there already. “When I hit the stage, people better be ready,” he says in “Get on Up.” “Especially the white folk.”

After playing Mr. Robinson and Mr. Brown, many would have turned a blind eye to biopics. But by playing a young version of the Supreme Court justice in “Marshall,” which he co-produced, Mr. Boseman confirmed the ongoing nature of his project, one that would reach a staggering climax in “Black Panther.” Mr. Boseman made his debut as King T’Challa in “Captain America: Civil War” in 2016, the same year he was diagnosed with colon cancer. “We all know what it’s like to be told that there is not a place for you to be featured — yet you are young, gifted and black,” Mr. Boseman said, accepting the 2019 Screen Actors Guild Award for best ensemble for “Black Panther.” “We know what it’s like to be told there’s not a screen for you to be featured on, a stage for you to be featured on. ... We know what it’s like to be beneath and not above. And that is what we went to work with every day,” Mr. Boseman said. “We knew that we could create a world that exemplified a world we wanted to see. We knew that we had something to give.”

He faced down an industry’s historical prejudice while suffering through cancer treatments. In less than a decade, Mr. Boseman changed the movies. In last year’s “21 Bridges,” a film he also produced, Mr. Boseman played an NYPD detective whose cop-killer case uncovers the department’s own persistent corruption. Mr. Boseman’s very presence reorients the story.

He worked through the cancer when he played a young, aware Black leader — seen only in flashbacks and visions — whose death is mourned by Vietnam War comrades-in-arms in Spike Lee’s “Da 5 Bloods.”

The cancer was there last summer when Mr. Boseman completed one last performance, in a Netflix adaptation of “Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom,” a play by his hero, August Wilson.

During the filming of “Black Panther,” Mr. Boseman said he was communicating with two boys who had terminal cancer. They were hoping to make it long enough to see the film. “I realized they anticipated something great,” Mr. Boseman said in a SiriusXM interview. The kids, Mr. Boseman said through tears, didn’t make it.

In the final tweet that he wrote himself on Aug. 11, he shared a photo of himself with U.S. Sen. Kamala Harris of California, a fellow Howard University alum, on the day she was chosen as Democrat Joe Biden’s vice presidential nominee.

“YES @KamalaHarris!” he tweeted. The photo showed him and Sen. Harris embracing and laughing. He added emojis of three hands clapping and the hashtags #WhenWeAllVote and #Vote2020.

On Aug. 28 after Mr. Boseman’s death, Sen. Harris tweeted a photo of the two of them at the same event, adding, “Heartbroken. My friend and fellow Bison Chadwick Boseman was brilliant, kind, learned and humble. He left too early but his life made a difference.”

His family issued a statement after his death.

“A true fighter, Chadwick persevered through it all, and brought you many of the films you have come to love so much,” his family said. “It was the honor of his career to bring King T’Challa to life in Black Panther.”

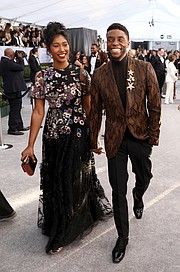

Mr. Boseman is survived by his wife, Taylor Simone Ledward, whom he married a few months before his death; his parents, Leroy and Carolyn Boseman; and two brothers.