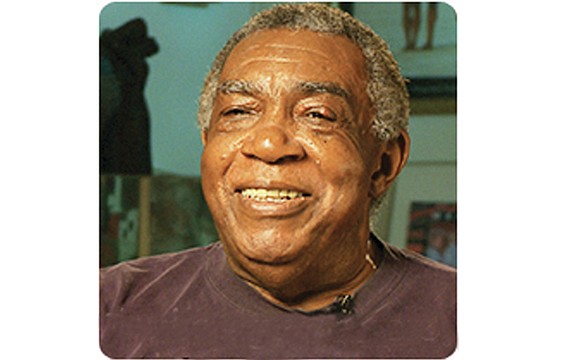

Soul music in Black cultural history, by A. Peter Bailey

8/26/2021, 6 p.m.

During the past five weeks, I have seen three films that showcase and celebrate the contributions of soul music to the cultural history of Black people.

“Summer of Soul” celebrates soul music’s contributions to the 1969 Harlem Arts Festival; “Respect” celebrates the key role of it in the life of Aretha Franklin who was, and for many, still is the Queen of Soul; while “Ailey” celebrated its role in the life of Alvin Ailey, a master choreographer whose “Revelations” is one of the greatest artistic creations of the 20th century.

Alvin told me when I assisted him in the writing of his memoir, “Revelations, theAutobiography of Alvin Ailey,” that “Revelations began with the music. As early as I can remember I was enthralled by the music played and sung in the small Black churches in every small Texas town my mother and I lived in. No matter where we were during those nomadic years, Sunday was always a church-going day. There, we would absorb some of the most glorious singing to be heard anywhere in the world. With profound feelings, with faith, hope, joy and sometimes sadness, the choirs, congregations, deacons, preachers and ushers would sing Black spirituals and gospel songs. They sang and played the music with such fervor that even as a small child, I could not only hear it, but almost see it.”

Aretha was equally “enthralled” by the Black music she first heard when attending Black churches as a small child. She absorbed it all and used that spirituality in all of her songs. This is clearly evident when hearing Jennifer Hudson brilliantly sing Aretha’s masterpieces in the film. Aretha also used that same powerful spiritual and communal spirit as a force for bringing Black people together during the Civil Rights Movement.

The same intense feelings described by Alvin and Aretha also are created by the singing of, among others, Mahalia Jackson, B.B. King, Nina Simone, Mavis Staples and Gladys Knight in the “Summer of Soul.” It was evident when watching and feeling the intense reaction of the thousands of Black folks—from small children to senior citizens—who attended the festival.

Watching the three films brought about precious memories since I attended the Harlem Arts Festival, assisted Alvin Ailey in writing his autobiography, as well as having seen “Revelations” at least 20 times through the years and attending at least a dozen Aretha Franklin concerts while living in Harlem.

Don’t get me wrong. The films were not flawless. “Summer of Soul” should have featured at least two songs by B.B. King and Gladys Knight. “Ailey” failed to note the major role played by Carmen de Lavallade in Alvin’s entry into the world of dance. “Respect” was hampered by occasional repetition that made it overly long.

Still, if my eight grandchildren, ages 8 to 28 lived here in D.C., I would take them as a group to see the films and then discuss with them the importance of soul music in our cultural history.

The writer is an author and teacher and can be reached at alfonzop.bailey@gmail.com.