Vacancies hurting Richmond’s emergency operations

Jeremy M. Lazarus | 8/26/2021, 6 p.m.

Every element of public safety in Richmond is under stress due to manpower shortages.

For example, an ambulance took 22 minutes to show up to a shooting scene Tuesday afternoon in South Side — or more than double the standard response time.

And the emergency transport for the most seriously wounded person, who died at a nearby hospital, had to come from Chesterfield County. The Richmond Ambulance Authority, which is short-staffed, had its entire cadre of paramedics and vehicles tied up on other calls, the RAA reported.

Separately, city firefighters are working back-to-back, 24-hour shifts — a previously taboo practice, according to Keith Andes, president of the union local that represents them. He said “no one blinks an eye” at the change that is aimed at ensuring there are sufficient trained personnel to respond to calls.

“My members are flat worn out,” Mr. Andes stated in an email response to a Free Press query. He said the heavier workload is forcing firefighters to spend more time away from their families and is taking a toll on their mental and physical health.

Meanwhile, the Richmond Justice Center, the city’s jail, still reports at least 100 vacancies among the deputies who monitor and guard the inmates. The staff shortage makes it harder for those remaining to do their jobs, making them more vulnerable to attack and leaving inmates more in control of cellblocks.

But the most serious situation may involve the Richmond Police Department, which now has 118 vacancies among its sworn officers, including 39 positions that City Hall has blocked the department from filling to help balance its budget.

According to the department, RPD has an authorized strength of 756 officers, which includes 45 for slots for recruits. Currently, 38 are in training, but only half, 19, will graduate from the academy in September, and none would be street-ready without additional field training under the tutelage of a more experienced officer.

The upshot: Of the 711 positions for sworn officers who can work on their own, only 592 are currently filled, taking the force by some estimates to its lowest level in years.

That number, however, is further reduced because all of those officers are not available. On any given day, 30 to 40 officers will be testifying in court, on vacation, nursing injuries, recovering from illness, serving in the National Guard, away on family medical leave or sidelined for an investigation of claims of violations of one or more department policies.

That is reflected at roll calls. Recently, First Precinct in Church Hill had only two officers to report for a shift, instead of the 15 or so who should be on hand.

The city’s three other precincts are regularly reporting that three to six people are available per shift. Only one officer was available to work a Saturday night in Shockoe Bottom when the bars emptied, compared with the squad of five to six officers who previously had been assigned the duty.

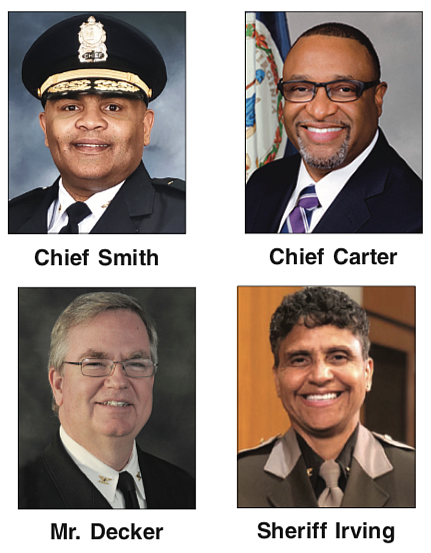

Police Chief Gerald M. Smith downplayed the situation in a report to City Council’s Public Safety Committee last month. He reported only 76 vacancies at the time and said the recruits in training would provide some relief. He also did not mention the frozen positions.

Despite his positive view, officers are expressing concern about the dwindling ranks and retirements that mean more mandatory overtime for those remaining. With violent crime up 14 percent and shootings rampant, officers on patrol are flooded with 911 calls and often must overlook lesser crimes.

“It’s fair to say we are in a crisis,” said an officer who commented on condition of anonymity due to concern about retaliation from superiors. “We’re working our butts off, and we can’t catch a break.”

The department has been facing a turnover problem since April 2020 after the pandemic hit, followed by the surging racial justice protests in which Richmond officers were often pelted with rocks and hit with bags filled with urine. More than 80 officers retired or resigned through June 30, 2021, a big increase for a department that usually loses 45 officers a year.

The loss of officers has continued. Since Chief Smith’s report to the committee, at least three more officers have left, and the department has noted that five officers have submitted notices that they will retire by the end of the year.

Internal reports the Free Press has received suggest the attrition among officers could be far greater. The Free Press was told the retirement count could go as high as 12 by Thanksgiving.

The Free Press also was told that 50 younger Richmond Police officers have applied or been hired by police departments at Virginia Commonwealth University and in Chesterfield, Henrico and other nearby counties that offer better pay and more stable working conditions.

If that happens, the total available force on any given day could drop below 500 people, the numbers indicated.

Richmond is not alone. Both private companies as well as government agencies in Virginia and across the country are reporting problems in finding workers to fill vacancies.

And police departments are among the most challenged to recruit new people, according to national and state police chiefs.

In a majority-minority city, recruiting is harder for Richmond’s public safety operations, which face budget limits and must seek diverse recruits. Assistant Fire Chief Andrew Snead told the Public Safety Committee in July that his department received more than 800 applications from experienced firefighters who want to transfer in or from people who want to be firefighters. He said that more than 85 percent of the applicants were white. He said only about 27 total would be offered positions or entry into the academy in large part due to diversity considerations.

For the city, there are some hopeful signs. Chip Decker, chief executive officer of the Richmond Ambulance Authority, said that he has hired 18 people who will help fill a portion of his 40 vacancies.

He said that, despite a $1 million reduction in the city’s subsidy in each of the last two years, he has been able to start increasing pay for paramedics and emergency medical technicians and believes he could be back to full strength in six to 12 months.

Fire Chief Melvin Carter told the Free Press that he has ap- plied for a federal grant that would allow him to hire 60 more firefighters to relieve the need for mandatory overtime. He said he currently has 33 vacancies — 42 counting frozen positions — some of which should be filled by October. About 10 to 12 trained firefighters have been hired as transfers from other fire departments.

Whether that will provide relief is uncertain. The Free Press has been told at least 25 current firefighters have applied to or been hired by departments in neighboring counties, and Mr. Andes is anticipating the loss of an additional 15 to 20 firefighters by the end of the year.

For Chief Smith and city Sheriff Antionette V. Irving, there appears to be no relief in sight. Both have advised that their recruiting efforts have not gone well.

Chief Smith said he is trying “to move money around so we can fill some of the frozen positions.” He also has started taking his executive team to roll calls to speak with officers and offer praise for their work. Whether that will help retention remains to be seen.