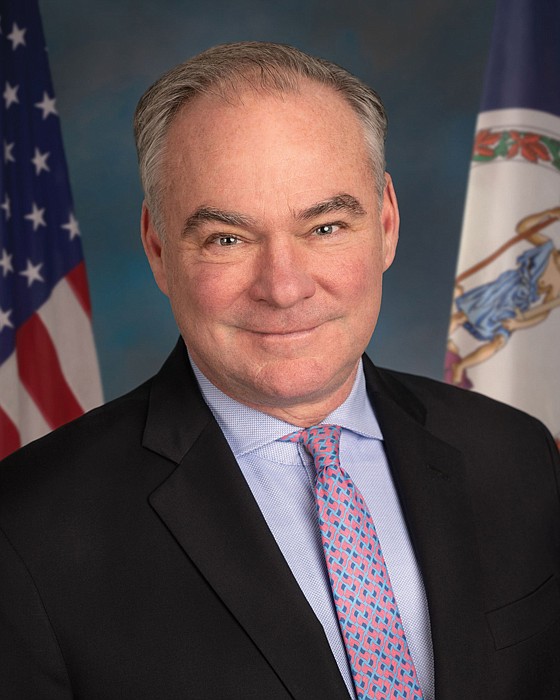

Protecting voting rights, by Sen. Tim Kaine

1/27/2022, 6 p.m.

I’ve served in elected office since 1994 — first on the Richmond City Council, then as mayor, then lieutenant governor, governor, and now U.S. senator.

The Senate seat I currently hold was occupied for 50 years, from 1933 to 1983, by Harry F. Byrd Sr. and Harry F. Byrd Jr. It became known as the “Byrd seat.”

The Byrds were supporters of the Massive Resistance movement against desegregation and opponents of civil rights and voting rights legislation. Harry F. Byrd Sr. was one of 27 U.S. senators to vote against the Civil Rights Act of 1964. And he was one of only 19 senators to vote against the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

As we’ve discussed and debated voting rights legislation during the last year, the legacy of my senate seat has weighed heavily on me. I’ve wanted to change the trajectory of a seat that had been used to fight against voting rights to fight for voting rights.

The right to vote is foundational for all other rights. It’s about the equality of each

person. But it’s also the self-correcting mechanism for democracy itself: If voters don’t like the job a candidate or political party is doing, they can vote for another in the next election. That self-correcting mechanism only works if all people can participate, so excluding people from the franchise makes it harder for our democracy to function.

But that’s exactly what’s been happening across the country. Former President Trump’s Big Lie — that because he lost, there must have been fraud — led to the violent attack on the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021, and also has resulted in a wide-ranging assault on the right to vote. Numerous state legislatures have been animated by that lie to restrict voting access. That lie has led to harassment of and even death threats against hard-working local election officials.

Our response to these efforts to demean the integrity of our elections and fence people out of democracy must be to protect all Americans’ right to vote. That’s why I’ve spent months crafting and then fighting for the Freedom to Vote: John R. Lewis Act.

This legislation is about democracy itself. It’s about preventing mass disenfranchisement. This legislation would set standards for federal elections to ensure that people are able to cast their ballots, have confidence that those ballots will be counted with integrity and trust in the final results. It also would mandate that all campaign contributions be publicly disclosed and require non-partisan redistricting for congressional seats.

These provisions are popular with Republican, Democratic and Independent voters. Making voting more convenient and secure doesn’t just help one party. Here in Virginia, turnout jumped by more than 25 percent from 2017 to 2021 after the General Assembly expanded access to early voting and vote by mail — Virginians elected a Republican as governor after eight years of that seat being held by a Democrat. Virginia is proof that making it easier for people to participate means more people will participate, regardless of party.

Efforts to expand the franchise are good for democracy, even if they take time to pass. The Voting Rights Act of 1965 passed despite years of previous failures. It took a galvanizing act of violence, the vicious beating of John Lewis, then a young activist, on the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Alabama, to spur the final push to victory.

Even after the violent effort on Jan. 6 to overturn the 2020 election, we fell short in the Senate on voting rights last week because, despite unanimous Democratic support, we could find no Republican willing to vote for our bill. Efforts to restore the public filibuster, requiring both parties to take the Senate floor as was the case during much of Senate history, also narrowly failed.

But the history of voting rights legislation shows that today’s close defeat lays the foundation for tomorrow’s success. While the Senate did not succeed in passing voting rights legislation last week, we’re not done and won’t rest until we succeed.

The writer represents Virginia in the U.S. Senate.