2 men convicted of killing Run-D.M.C.’s Jam Master Jay nearly 22 years after rap star’s death

Jennifer Peltz and Cedar Attanasio/The Associated Press | 2/29/2024, 6 p.m.

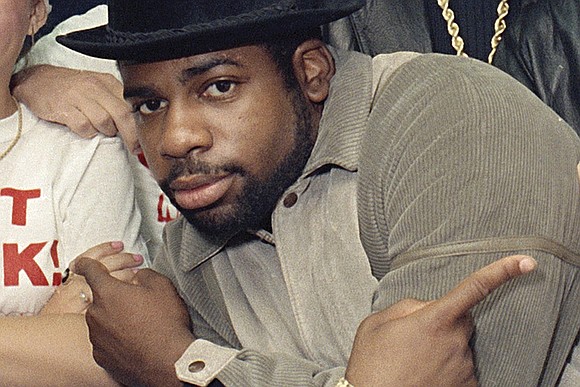

NEW YORK - More than 20 years after Run-D.M.C. star Jam Master Jay was brazenly gunned down in his recording studio, two men close to him were convicted Tuesday of murder, marking a long-awaited moment in one of the hip-hop world’s most elusive cases.

An anonymous Brooklyn federal jury found Karl Jordan Jr. and Ronald Washington guilty of killing the pioneering DJ in 2002 over what prosecutors characterized as revenge for a failed drug deal.

The musician, born Jason Mizell, worked the turntables in Run-D.M.C. as it helped hip-

hop break into the pop music mainstream in the 1980s with such hits as “It’s Tricky” and a fresh take on Aerosmith’s “Walk This Way.”

Like the slayings of rap icons Tupac Shakur and the Notorious B.I.G. in the late 1990s, there were no arrests for years. Authorities were deluged with tips, rumors and theories but struggled to get witnesses to open up.

Mr. Jordan, 40, was Mr. Mizell’s godson. Mr. Washington, 59, was an old friend who was bunking at the home of the DJ’s sister at the time of the shooting on Oct. 30, 2002.

Both men were arrested in 2020 and pleaded not guilty.

“Y’all just killed two innocent people,” Mr. Washington yelled at jurors following the guilty verdict. Mr. Jordan’s supporters also erupted at the verdict, cursing the jury.

Defense lawyers said they asked the judge to set aside the verdict and acquit them.

“My client did not do this. And the jury heard testimony about the person who did,” one of Washington’s lawyers, Susan Kellman, told reporters.

The men’s names, or at least their nicknames, have been floated for decades in connection to the case. Authorities publicly named Mr. Washington as a suspect in 2007. He told Playboy magazine in 2003 he’d been outside the studio, heard the shots and saw “Little D” — one of Mr. Jordan’s monikers — racing out of the building.

Relatives of Mr. Mizell welcomed the verdict and lamented that his mother did not live to see it.

“I feel like I was carrying a 2,000-pound weight on my shoulders. And when that verdict came today, it lifted it off,” said Carlis Thompson, Mr. Mizell’s cousin, who wiped away tears after the verdict was read. “The wounds can start to heal now.”

Mr. Mizell had been part of Run-D.M.C.’s anti-drug message, delivered through a public service announcement and such lyrics as “we are not thugs / we don’t use drugs.”

But according to prosecutors and trial testimony, he racked up debts after the group’s heyday and moonlighted as a cocaine middleman to cover his bills and habitual generosity to friends.

“He was a man who got involved in the drug game to take care of the people who depended on him,” Assistant U.S. Attorney Artie McConnell said in his summation.

Prosecution witnesses testified that in Mr. Mizell’s final months, he had a plan to acquire 10 kilograms of cocaine and sell it through Mr. Jordan, Mr. Washington and a Baltimore-based dealer. But the Baltimore connection refused to work with Mr. Washington, according to testimony.

Prosecutors said Mr. Washington and Mr. Jordan went after Mr. Mizell for the sake of vengeance, greed and jealousy.

While the case may complicate Mr. Mizell’s image, Syracuse University media professor J. Christopher Hamilton says it shouldn’t be blotted out.

If he was indeed involved in dealing drugs, “that doesn’t mean to say his achievements shouldn’t be lauded,” Mr. Hamilton said, arguing that acceptance from local underworld figures was a necessity for successful rappers of the ’80s and ’90s.

“You don’t get these individuals without them walking through the gauntlet of the street,” Mr. Hamilton said.