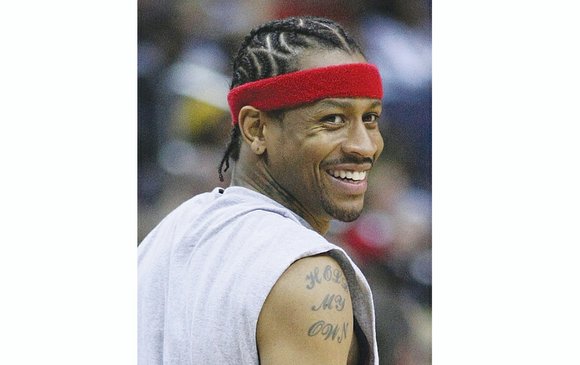

Allen Iverson lone Virginian to be inducted into Basketball Hall of Fame

Fred Jeter | 4/29/2016, 12:32 p.m.

Richmond’s high schools got an early glimpse of Allen Iverson’s athletic greatness.

Before taking his talents to Georgetown University, the NBA and what will soon be the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame, Iverson left his mark on RVA.

Iverson will be the lone Virginian inducted into the Hall of Fame on Sept. 9 in Springfield, Mass.

A football quarterback, Iverson led Hampton’s Bethel High School to the 1992 State Group AAA, Division 5 title with a semifinal win over Richmond’s Huguenot High School (22-16) and victory over E.C. Glass High School of Lynchburg (27-0) in the finals.

In addition to quarterbacking, Iverson returned a punt for a 60-yard touchdown against E.C. Glass High and had a touchdown saving interception in the end zone.

Iverson then paced Bethel High to the State Group AAA basketball crown with a championship game win over Richmond’s John Marshall High School (77-71) at the University of Virginia.

Iverson collected 28 points in the state finale, giving him the Virginia High School League record of 948 points for the season in 31 games. John Marshall High’s E.J. Sherod had 34 points for the Justices.

“AI” was named State Player of the Year for both football and basketball by the Associated Press.

As a senior, Iverson did not compete because of legal problems incurred during an altercation at a Newport News bowling alley.

A look at the basketball icons to be honored posthumously in Springfield:

A search for America’s first great African-American basketball player might lead historians to the Pittsburgh suburb of Homestead, Pa., in the early 1900s. That’s where information might be gathered on Cumberland Posey Jr. (1890-1946), aka “Charlie Cumbert.”

Posey was a megastar in what is known as the Black Fives era of basketball, when all-black teams competed from 1906 to 1950, before the all-white NBA dropped its color barrier.

The light-complexioned son of a railroad engineer who was president of the Pittsburgh Courier newspaper, Posey led the Monticello Rifles to the 1912 Colored Basketball World Championship.

Later he paced the Loendi Big Five to four straight Colored World crowns, 1920 through 1923. Both Monticello and Loendi were based out of the Pittsburgh area.

In between the world championships, he led Duquesne University in scoring in 1916, 1917 and 1918 under the assumed name Charlie Cumbert.

There are two theories for the hidden identity — to dodge questions of professionalism because some money may have changed hands during the world tournament and to pass as white at then all-white Duquesne University.

An exquisite athlete, Posey also played baseball for the Homestead Grays of the Negro National League and later managed and owned the team.

Posey becomes the only person selected to both the baseball (2006 induction in Cooperstown, N.Y.) and basketball Hall of Fames.

In 1988, he was selected to the Duquesne Athletic Hall of Fame, not under an alias, but under his real name, Cumberland Posey.

•

Zelmo Beaty (1939-2013), out of Prairie ViewA&M University in Texas, becomes the fourth inductee into the Hall of Fame from an HBCU following Willis Reed (Grambling), Sam Jones (North Carolina Central) and Earl Monroe (Winston-Salem State University).

The agile 6-foot-9 Beaty was picked by St. Louis as the third overall choice of the 1962 NBA draft. At the time, he was the highest-round pick ever selected from an HBCU. It was a bold but wise choice.

Beaty was among the few players who could battle the top big men of the day — Boston’s Bill Russell and Philadelphia’s Wilt Chamberlain — on fairly even terms.

Following a brilliant career with the NBA’s Hawks and Lakers and the ABA’s Utah Stars, “Big Z” briefly coached the ABA’s Virginia Squires in 1975-76.

•

In coaching stints at Hampton Institute, Tennessee State, Kentucky State, Cleveland State and North Carolina College of Negroes, John McLendon (1915-1999) won an official 496 college games.

Then, unofficially, there was “the secret game.”

While much of Durham was attending church on a Sunday morning, March 12, 1944, McLendon quietly arranged for his all-black North Carolina College Eagles (coming off a 26-1 season) to play all-white Duke University, the Southern Conference champs, just across the town.

This was unheard of — even illegal — during that segregated period in the South and those involved kept the matchup hush-hush.

Secretly, the teams met on the NCC campus (the school is now called North Carolina Central University) with doors locked, windows covered and no constables or mainstream media in sight. It is considered the first integrated basketball game in the South, albeit unofficial.

After a spirited contest, both sides agreed NCC had won decisively, with an uptempo style Duke had never seen.

But the story gets better. After a short rest, the young men decided to play again, mixing the lineups to even the sides.

Instead of playing against each other, they played with one another.

As it turns out, Coach McLendon’s “secret game,” a game that officially didn’t count, in the end might have counted most of all.

Additionally, the CIAA Hall of Fame is named for Coach McLendon.