‘Kehinde Wiley: A New Republic’ opens Saturday at VMFA

6/10/2016, 7 a.m.

By Toni Wynn

Special to the Free Press

Asked what “A New Republic” means, visual artist Kehinde Wiley replies rapid-fire.

“It’s a space-clearing gesture.”

As the 20th century dawned, artists created modernism as a place where they could “create zones of new conversations,” he explained, throwing off the constraints of the old and too familiar.

Mr. Wiley’s “new space of undiscovered country” becomes a new republic of the 21st century.

Who populates this republic?

We all can if we feel the urgency of conversations about black bodies and how they represent and are represented in society.

When Mr. Wiley speaks of “a broader need to redefine ways bodies are coded,” his artwork speaks louder than words.

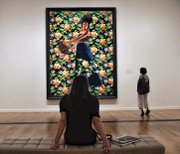

Nearly 60 portraits in this mid-career retrospective by Mr. Wiley, 38, will be on view beginning Saturday at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts in Richmond.

The exhibit, “Kehinde Wiley: A New Republic,” was organized by the Brooklyn Museum and has toured the country and most recently drawn acclaim at the Seattle Art Museum. The next stop, Richmond’s VMFA, is halfway through the tour.

Sarah Eckhardt, associate curator of Modern and Contemporary Art at VMFA, organized the local exhibit, which runs through Sept. 5.

“When you see the paintings together, you see the scope of his vision, which is big. He’s clearly putting African-American men — and now women and people of color from all over the world — into the center of the composition. That, to me, forms a new republic,” Dr. Eckhardt said.

In 2006, under the direction of former senior curator John Ravenal, the VMFA purchased Mr. Wiley’s “Willem van Heythuysen,” a 96” x 72” portrait, for the museum. “Our painting is from the time when he was just establishing himself,” Dr. Eckhardt said.

The exhibit opens with the VMFA’s painting, allowing visitors to see how the portrait fits into the whole of Mr. Wiley’s work. Given the majesty of the piece, it’s not a heavy lift to appreciate it.

But the artistic reference — the backstory — is well worth considering. In 1625, Dutch artist Frans Hals painted “Willem van Heythuysen posing with a sword.” Nearly 400 years later, Wiley posed a young African-American man similarly, painted his portrait on a huge canvas and used van Heythuysen’s name for the work.

A “space-clearing gesture,” indeed.

Of Mr. Wiley, Richmond native Juliette Harris, noted former editor of the International Review of African American Art published at Hampton University, said, “His works are stunning — the unexpected combination of figures from the ’hood with the opulent Renaissance-era backgrounds. He’s taking these figures that are considered commonplace and heroically elevating them in such an unstinting way of all-out glorification.

“They’re huge, jaw-dropping, so intricately wrought,” she said. “The rendering is so beautiful. Those skin tones! The execution is just very difficult and the works are epic, heroic.”

Mr. Wiley has taken heat for the actual execution of his paintings. He employs assistants who work in his studios, taking direction from the artist to help create the portraits’ ornate backgrounds.

Here again, Mr. Wiley is following tradition.

“Reubens, Rembrandt had huge studios,” Dr. Eckhardt said. For 20th-century conceptual artists and minimalists, “emphasis was on the concepts — it was important not to make the art themselves.

“Wiley has an enormous vision,” she continued. “You have to have people working alongside you to work at that scale,” she says.

There’s a balance between the professional and the personal, the wide open and up close. Mr. Wiley sees his process as “very open.”

He uses street casting — basically, asking passersby on the world’s streets to model for him — and documents the encounters. But he also wants the viewer in his head.

“The studio practice, how the paintings are made, convincing people to model for me, the act of seduction — this is an integral part of what it should be to experience the painting,” he said in a telephone interview last week with the Free Press.

“It’s about me looking, me seeing the world through sexual desire, political interest, desire to decode certain questions for myself. It’s about a black American going through the streets of black America and walking through the world.”

Other criticisms revisit the middle-school markers: Is Wiley black enough? Too black? Does he meet shifting and arbitrary standards and expectations?

“So much is expected of our artists,” said Mr. Wiley, a queer man of African- American and Nigerian heritage. “There’s a difference between what black American artists are expected to do as opposed to what heterosexual white Americans are expected to do.”

Ms. Harris thinks African-American artists need to pursue their vision without regard to how it can help the community.

“I think it’s wonderful that we feel this commitment … but it can hold you back. It can empower your work, give you passion. But it can also limit you. It’s a very delicate balance between the motivation and the limitation aspects of being a socially concerned artist,” Harris said. But after a point, she added, “[Wiley] should be held accountable.”

Art historian and cultural writer John Welch sees Mr. Wiley’s work “as much a focus on thought-provoking social and political realities of ‘blackness,’ as it is an attempt to realize, through facility with paint, a singular beauty.”

Is the VMFA is a safe space for the kinds of difficult or controversial conversations Mr. Wiley’s work elicits?

“On one level, the paintings are beautiful. On another level, they ask questions about who’s in power. Who’s in the privileged position? Why weren’t people of color in these [classical] paintings?” Dr. Eckhardt points out.

“A New Republic” contains pieces from Mr. Wiley’s World Stage series, which Dr. Eckhardt sees as addressing the history of colonialism.

“That’s the not the only way to look at the paintings, but it is one way,” she said. The VMFA invites us to “come look and have those conversations.”

In addition to his dazzling portraits, Mr. Wiley’s bronze busts are included the show.

Why work in bronze?

“Timelessness,” Mr. Wiley replies. “The illusion of fighting against time and decay. Sculpture is a stand-in for what we value most in society.”

In his hands, sculpture “celebrates an aspect of African-American culture.” We’ll see how Monument Avenue affects him.

The opening of “A New Republic” will bring Mr. Wiley to Richmond for the first time. Asked how he thinks visitors will respond to the show, Mr. Wiley deflects.

He’s not looking for “a site-specific response. Each [city] has its own cultural temperature,” he said.

For his part, Mr. Wiley is hoping to “get in a little fishing” while he’s here. Let’s hope the temperature is right.