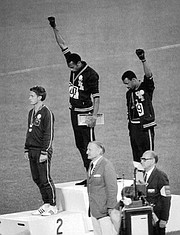

Olympic ‘Black Power Salute’ rises 50 years later

Fred Jeter | 11/1/2018, 6 a.m.

Why one glove each?

Despite much planning for their 1968 “Black Power Salute” at the Mexico City Olympics, athletes Tommie Smith and John Carlos ran into a snag — and a light-hearted moment.

Carlos forgot to bring his pair of black gloves to the awards ceremony, having absent-mindedly left them in the Olympic Village.

Realizing the show must go on, Smith gave his left glove to Carlos, while keeping the right for himself.

Mission accomplished.

Tommie Smith and John Carlos were among the fastest men of their generation.

But it wasn’t what they did on the Olympic track that makes them most remembered. It’s what they did after their race — on the medals podium — that still resonates.

Now in their 70s, Smith and Carlos returned to their alma mater, San Jose State University, earlier this month to celebrate the 50th anniversary of arguably the most overtly political statement in sports history.

On Oct. 16, 1968, Smith finished first and Carlos third in the 200-meter sprint during the Summer Olympics at Ostadio Olimpico in Mexico City.

Later that evening, the African-American runners seized global attention with a brazen gesture by standards of the day as they stood on the winners’ podium and raised what has come to be known as the “Black Power Salute.” The world was stunned.

Here’s how it went down.

First, Smith and Carlos were presented their medals by David Cecil, the 6th Marquess of Exeter.

As the “Star-Spangled Banner” began to play, the men bowed their heads, each raising one fist above their head while wearing a black glove.

It was a sign meant to underscore “black strength and unity.”

There’s more. They arrived at the podium in black socks, shoeless, suggesting black poverty.

Also, Smith wore a scarf around his neck signifying “black pride.”

Carlos left his jacket unzipped, honoring blue collar workers, and wore beads around his neck, meant to condemn lynching and racially based violence.

The immediate reaction was highly critical, at least among Olympic officials and much of the audience. Fans in attendance booed. International Olympic Committee President Avery Brundage was so enraged that he nullified their medals and demanded they leave the Olympic Village. Essentially, their track careers were over.

Here’s what the athletes told the press at the time:

Smith: “We were concerned about the lack of black assistant coaches. About how Muhammad Ali got stripped of his title. About the lack of access to good housing and our kids not being able to attend top colleges.”

Carlos: “We are black and proud of being black. Black America will understand what we did.”

While the sprinters were ostracized by many at the time, they have come to represent the living embodiment of idealism and the Olympic spirit.

The iconic photo of their salute was taken by John Dominis, then working for Life magazine. A 22-foot statue based on that photo has been erected at San Jose State, where Smith and Carlos recently enjoyed a reunion.

Smith, from Clarksville, Texas, and Carlos, from Harlem, were strongly influenced by San Jose State Sociologist Harry Edwards, who started the Olympic Project for Human Rights.

These were racially raw times in America at the height of the Civil Rights Movement. There were protests over the United States involvement in Vietnam, anti-poverty protests and riots in the cities after the assassinations of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert F. Kennedy.

The progressive Edwards went so far as to encourage an African-American boycott of the 1968 Olympic Games. That didn’t happen. But what did happen — Smith and Carlos’ protest — is still being talked about a half-century later.

This isn’t just a black and white story. The forgotten man here is Peter Norman, the white Australian who finished second in the 200-meter race and who is prominent in the 1968 photo.

Simpatico to his black competitors’ cause, Norman joined the OPHR and wore the same patch as Smith and Carlos on the podium. The three became lifetime friends. At Norman’s death in 2006, Smith and Carlos served as pallbearers in Melbourne, Australia.

While ridiculed at the time, the “Black Power Salute” not only brought black Americans closer together, but also fair-minded people of all backgrounds.