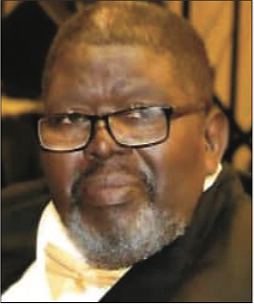

Preddy D. Ray Sr., longtime affordable housing advocate who sought to keep people in their neighborhoods, dies at 69

Jeremy M. Lazarus | 3/26/2020, 6 p.m.

In 1971, Preddy Drew Ray Sr. was among a group of nine Richmond college students who packed their bags and went to a Cincinnati conference on af- fordable housing and the role community groups could play.

“We saw black people from all walks of life fighting to save their communities,” Mr. Ray stated in a 1995 Free Press Personality feature. “We wondered why we weren’t doing the same thing in Richmond.”

Inspired, the Richmond native and longtime Carver neighborhood resident would go on to found and lead the nonprofit Task Force for Historic Preservation of the Minority Community to fight gentrification through advocacy and through buying, renovating and selling houses at a reasonable cost to keep people in the community.

While the Task Force ultimately would collapse and lead to recriminations, Mr. Ray’s innovative efforts to use low-income tax credits and other financial tools in development drew the attention of other nonprofit housing groups and encouraged Richmond City Council to create a program using property taxes to stimulate renovation.

“He was a leader and a visionary,” said longtime friend James H. Elam, a veteran community organizer and past president of the now defunct nonprofit Church Hill Neighborhood Inc. that also engaged in housing improvement.

Mr. Ray’s efforts in housing and in other areas, including aiding in laying the foundation for the Black History Museum and Cultural Center of Virginia, are being remembered following his death on Saturday, March 14, 2020, that ended his battle with multiple health challenges. He was 69.

With only family members allowed, Mr. Ray was paid final tributes during a funeral on Saturday, March 21, at Ebenezer Baptist Church in Jackson Ward, where he was a member.

A big man who played football at Armstrong High School and graduated from Virginia Commonwealth University, Mr. Ray began the Task Force in 1981. He got involved in the project after working as a substance abuse counselor, as a juvenile corrections counselor and as an employment training counselor at the Richmond OIC, or Opportunities Industrialization Center.

Joined by community-minded people such as Mr. Elam, Umar Kenyatta and Carson Kittrell and a host of churches, Mr. Ray sought to “improve the quality of life for low- and moderate-income people through housing.”

Buoyed by a grant from the Ford Foundation, he began buying houses in Jackson Ward and Church Hill and worked with others to keep them affordable after renovation and improvement. In his view, it was important to emphasize the history to counter the view that property in black communities was worthless, which he felt triggered “black flight” to the suburbs and the abandonment of once strong neighborhoods.

“Our effort must be to recapture the spirit of community,” he stated in the Personality feature.

Outspoken and known for vigorously expressing himself in letters published in area newspapers, including the Free Press, he battled the urban renewal approach of the Richmond Redevelopment and Housing Authority that involved demolishing and replacing decaying houses rather than renovating them. He pushed for banks and other regulated financial institutions to lend in black neighborhoods as required under the federal Community Reinvestment Act.

His work for affordable housing extended beyond Richmond. He served on the boards of the National Low-Income Housing Coalition and Low-Income Housing Information Service.

According to his wife, Cassandra Calender-Ray, the long-time executive director of the adoption group Virginia One Church, One Child, Mr. Ray also was passionate about the need to create jobs and believed that the community had to benefit economically from development.

The Task Force, however, became financially overextended by 1997 and lost the final 13 non- renovated properties in bank- ruptcy in 2001 after an extended fight that for years kept creditors at bay, but drew criticism from neighbors who considered the decaying buildings a threat to their properties.

He later developed the Housing Preservation and Development Corp. in a bid to continue the work, his wife stated in the funeral program, though his health challenges largely blocked that effort.

While organizing the Task Force, the history buff also began a project called “Museum in a Trunk,” that collected photos, documents and memorabilia from families as part of creating a black-oriented museum, Mrs. Calender-Ray stated.

When Carroll Anderson Sr. organized the Black History Museum in 1981, Mr. Ray became a founding board member.

After shutting down the Task Force, he created the nonprofit Richmond Hiring Hall and business incubator near Adams and Leigh streets in Jackson Ward as a center to connect people to jobs and provide space for start-up companies. He was unable to attract the resources to make it work and eventually closed it.

While still with the Task Force, he was proud of playing a role in organizing the North of Broad Youth Group and the creation of one of the first community gardens in the city, both in Church Hill and both grassroots efforts, his wife stated.

Mr. Ray also was passionate about cooking and baking and was a devoted jazz fan. He also was a longtime member of Phi Beta Sigma Fraternity and was among the inaugural pledges of the VCU chapter.

In addition to his wife, survivors include his son, Preddy D. Ray Jr.; a daughter, Maya E. Ray; three brothers, Obie A. Ray, Victor R. Ray and Waverly E. Ray; two sisters, Brenda Ray Taylor and Carolyn R. Solomon; and two grandchildren.