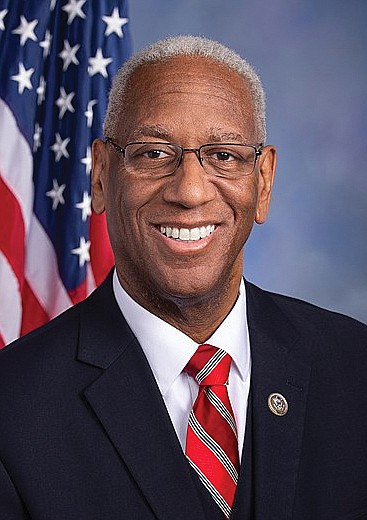

Equal protection under the law, by Rep. A. Donald McEachin

5/21/2020, 6 p.m.

In February, Ahmaud Arbery was hunted and shot down by neighborhood vigilantes while jogging in Brunswick, Ga. His killers were not taken into custody until a national outcry over leaked footage of the assault three months later.

That is unacceptable.

Every day on social media, by phone and in mail correspondence, I hear from critics challenging me to “move on” or to “not bring race into everything,” referring to my efforts in Congress to address the systemic racism ingrained in America’s status quo. I wish that I could help them understand that, for many, Ahmaud’s death running from men who assumed a right to determine his fate based solely on his skin color is eerily similar to the hundreds of photos of dead black men, women and children who dangled at the end of ropes af- fixed like strange fruit to Southern and Midwestern trees.

It is clear that our nation has far more work to do.

Too many remain silent as black America vacillates between anger and grief, grappling with the increasing weight of our cumulative trauma and racial vio- lence as we watch black bodies reminding us of our siblings, children, parents and friends bleed out on the concrete.

Each time, the men behind the triggers watch the life escape their victims’ bodies.

And, most times, believing themselves to be a singular authority — judge, jury and executioner — they don’t call for an ambulance or offer first aid.

The silence and willingness to justify Ahmaud’s murder in Brunswick are re- flective of the long-standing American inner monologue that holds black people to blame for their own suffering at the hands of racist violence. Even in cases with insurmountable evidence, indictments are always rare and are even less frequently followed by convictions.

In social media comment sections and presidential news conferences alike, people form rationalizations like:

“If only the audio were clearer, we’d know for sure he was innocent.”

“He was afraid for his life, he had to defend himself.”

“The video doesn’t show all the angles. He could’ve been reaching for a gun.”

Thirty years ago, Ahmaud could have been me. As a black man in America, I know too well the feeling of being fol- lowed and suspected. Today, as a black father in this country, much remains the same. I am haunted with the same fear now for my own children — that they might one day find themselves victims of a senseless, racist assault.

That is not the America I believe in, but it is the America too many of us know. We must continue to demand better.

The impending investigation must hold the parties responsible accountable and reflect the most basic tenet of America enshrined in the Constitution — that equal protection under the law applies to us all.

We cannot continue to allow dead men who were already assumed guilty by their assailants to be placed on trial for their own murders in the court of public perception. This pattern of pre- sumed guilt is especially reserved for black people in America, pervading our collective national consciousness and leaving men like Ahmaud lying on the asphalt breathing their last breath.

We all want so desperately to have moved forward; to step finally into the light on the other side of the shame- ful wounds of genocide, slavery and inequality that blight our nation’s past that it becomes easy to relegate things like racism to history — something to be associated with long gone civil rights leaders and politicians and folded away in long discarded Klan sheets and hoods.

When this is the approach we take, it is easy for some to believe racist brutality as being invalid and, if existent, not racially motivated.

We cannot afford to relive that revisionist history anymore.

The writer represents the 4th Congressional District, which runs from Richmond south to the North Carolina border and includes all or parts of Richmond, Petersburg, Hopewell, Colonial Heights, Emporia, Suffolk and Chesapeake and the counties of Henrico, Chesterfield, Charles City, Prince George, Dinwiddie, Greensville, Southampton, Surry and Sussex.