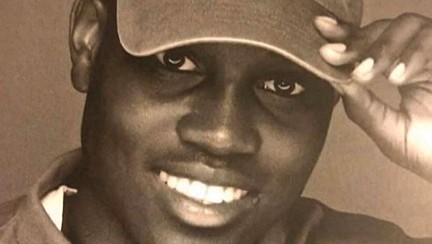

Murder trial of three white men in the death of jogger Ahmaud Abery refocuses national spotlight

Free Press wire reports | 10/28/2021, 6 p.m.

BRUNSWICK, Ga. - The glare of the national spotlight is focused on this small city of 16,000 on the Georgia coast that is the now epicenter of the sensational racial profiling trial of three white men accused of murder in the slaying of an unarmed Black jogger, Ahmaud M. Arbery, who was running in their neighborhood.

Jury selection continued for the seventh day Wednesday as lawyers and trial Judge Timothy Walmsley culled through a pool of 600 people in a bid to secure 16 jurors — 12 decision-makers and four alternates.

“I’m praying for an impartial panel and a fair trial,” Mr. Arbery’s father, Marcus Arbery Sr., told reporters. “This is 2021, and it’s time for a change,” he said. “We need to be treated equally and get fair justice as human beings because we’ve been denied for so long.”

A two-week trial is anticipated once the jury is seated in this closely watched case that is on a par with the trial in the police murder of George Floyd in distant Minneapolis.

A cellphone video showing the killing of Mr. Arbery was secured by a local newspaper and later went viral after being posted on social media, creating an outcry that pushed authorities to bring charges, just as happened in the case of Mr. Floyd.

The three men also are facing separate federal hate crime charges.

The case finally resulted in charges after Georgia’s governor, seeking to quell the uproar, intervened to get the Georgia state police to investigate the circumstances. Father and son Greg McMichael, 65, and Travis McMichael, 35, and their neighbor, William “Roddie” Bryan, 52, are facing felony murder and other charges related to the death of the 25-year-old Mr. Arbery, an electrician, on Feb. 23, 2020, in a suburban section Glynn County of which Brunswick is the seat.

According to the prosecution, the McMichaels, who were armed, pursued Mr. Arbery in their pickup truck while Mr. Bryan followed in another vehicle while videotaping the chase with his cellphone. According to the charges, they stopped and confronted Mr. Arbery. The prosecution has named Travis McMichael as the person who fired the fatal shot.

As part of the evidence the Georgia Bureau of Investigation gathered, Mr. Bryan told investigators that Travis McMichael called Mr. Arbery a “f...ing nigger” as he lay dying.

The defense, meanwhile, will seek to prove to the jury that the men were trying to make a lawful citizen’s arrest under a Civil War-era law that later was repealed amid the uproar over the shooting.

“Citizen’s arrest is a big part of our case, a big part,” Kevin Gough, a lawyer for Mr. Bryan, said before the trial held in Glynn County Superior Court. “They changed the law but changing the law doesn’t affect us. It doesn’t change what was the law of the land at the time.”

Mr. Gough said the defense will seek to show the three men thought Mr. Arbery was a burglar and sought to apprehend him as he ran down a street in mostly white Satilla Shores neighborhood.

Just before he was cornered and shot to death, security cameras had recorded Mr. Arbery entering a house that was under construction. The owner of the property has said nothing was taken and that Mr. Arbery, who was on a Sunday afternoon jog, probably just stopped there for a drink of water.

According to Greg McMichaels, his son fired in self-defense after Mr. Arbery punched him and tried to grab his weapon during the confrontation. Mr. Bryan’s video shows Travis McMichaels shooting Mr. Arbery three times with a shotgun.

His family and the prosecution believe the three men were suspicious of Mr. Arbery because he was Black.

Legal observers said that the prosecutors will have to convince the jury that Mr. Arbery had done nothing to justify the men’s actions.

Chris Slobogin, a law professor at Vanderbilt University, said citizen’s arrest laws put dangerous powers in untrained hands.

“Things can get out of control quickly,” he said.

Ira Robbins, a law professor at American University in Washington, has written a treatise on such laws and argued they often are overbroad in vesting citizens with arrest powers.

“While recruiting citizens to aid in eradicating crime is a noble idea,” Mr. Robbins wrote, strict safeguards are needed to prevent the law from being abused.