’His Airness’ Michael Jordan also knew how to swing a bat

Fred Jeter | 5/21/2020, 6 p.m.

Michael Jordan the basketball player is a global legend. His greatness is beyond debate.

Meanwhile, Jordan the baseball player remains a bit of a mystery, his status open to discussion.

The recent ESPN docuseries, “The Last Dance,” focuses on Jordan and the Chicago Bulls’ dynasty in the 1990s. But it also touches on the one outlying season of “His Airness” on the pro baseball diamond.

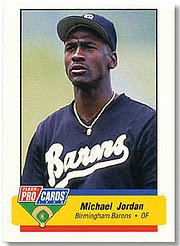

Jordan played right field in 1994 for the Birmingham Barons of baseball’s Class AA Southern League – the same level as the Richmond Flying Squirrels. The Barons were a farm club of the Chicago White Sox.

Anticipating a season of baseball, Jordan worked out in the indoor batting cage at Chicago’s Comiskey Park during winter 1994 with some White Sox players.

In Birmingham, he wore jersey No. 45, the same number he sported more than a decade earlier for Laney High School in Wilmington, N.C.

In 127 games, he hit .202 (88-for-436) with 17 doubles, one triple, 51 runs batted in and three home runs. He stole 30 bases in 48 tries.

Shaky defensively and inconsistent at the plate, Jordan made 11 errors and struck out 114 times.

Following the Barons’ season, he hit .252 for the Scottsdale Scorpions in the Arizona Fall League.

Jordan retired from baseball soon after to rejoin the Bulls and lead the franchise to three more NBA crowns.

While he was in Birmingham, the Barons shattered their season attendance record, drawing 467,867 fans to the Hoover Met complex. Likewise, the Southern League prospered, setting a record attendance of 2.4 million fans.

Jordan helped the Barons acquire a $350,000, 45-foot, 34-seat bus that came to be known as the “JordanCruiser.” All Class AA travel is via bus.

While playing for the Barons, Jordan lived in an upscale gated community called Greystone in the Birmingham suburb of Hoover, adjacent to a golf course. Among his golfing partners was ex-NBA great Charles Barkley.

After games, Jordan was often spotted at A.J.’s, a sports bar, and at Sammy’s Adult Entertainment, a topless gentleman’s club.

It has been noted he also developed a taste for grits.

While Jordan played for Birmingham, his actual contract was with the Nashville Sounds, the White Sox’s AAA

farm club. At the time, he was still earning about $4 million annually from the Bulls.

Considered “one of the guys,” Jordan engaged in friendly pickup basketball games with teammates at manager Terry Francona’s apartment complex.

Between games, Jordan was the focal point of a national television advertisement for Ball Park Franks.

So why the baseball experiment?

Theories include he was burned out with hoops; he was honoring his deceased father, James, who always wanted his son to play baseball; and rumors of a gambling addiction that may have persuaded him to escape the NBA spotlight.

One more theory: He was a classic case of “If you tell me I can’t do something, I’m going to show you I can.”

While Jordan brought success to the box office, it didn’t carry over to the field. The Barons finished nine games under .500.

The right-handed Jordan got his first hit, a single, in his eighth time at bat for the Barons. His first home run came in his 354th time up, July 30, 1994.

After seeing the blast disappear over the left field fence, Jordan kissed his fingers and pointed to the heavens, honoring his father, who had been murdered a year earlier.

Jordan left his mark on the Deep South. His No. 45 jersey adorns a wall of the Birmingham Barons’ front office and a conference room is named in his honor.

During his brief pro baseball career, Jordan insisted he was serious about the sport and coined the phrase, “It’s no gimmick.”

Opinions vary on Michael Jordan and baseball

Terry Francona (Michael Jordan’s manager in Birmingham; now manager of the Cleveland Indians), as told to Fox Sports: “I think that if he were willing to commit three years, I believe he would have found his way to the major leagues. I really believe that. One, because of the tools he had. But the other one, and maybe the more important, and I found out first hand, if you tell Michael “no,” he finds the answer to be “yes.”

John Stearns (veteran big league catcher and rival manager of Jordan’s team in the Arizona Fall League), as told to CBS Sports: “Michael can’t play baseball, but he’s not terrible. He doesn’t have power. He can’t throw. His instincts are poor. But he can run a little bit and hit a little bit. Considering he hasn’t played ball all these years, it’s possible he could make someone’s team as the 25th man and hold his own.”

Todd “Parney” Parnell (vice president and chief operating officer for the Richmond Flying Squirrels), as told to the Free Press on the subject of making the big leagues:

“It would be incredibly difficult for practically anyone, except someone like Michael, an other-planet athlete. But what he had to match his talent was his competitiveness. Whatever he was trying to do, he pushed himself, and others around him, to the limit. The guys he was playing with had one step left in the minors before the majors. It’s amazing he picked up a bat (after so long) and did what he did.”

In the dual zone

Only 13 athletes have ever played in both the NBA and Major League Baseball.

The most recent was Danny Ainge, who played baseball for the Toronto Blue Jays from 1977 to 1979 and then played in the NBA from 1981 to 1995.

Most “double dippers” were from long ago, like Chuck Connors, who suited up for the NBA’s Boston Celtics and MLB’s Brooklyn Dodgers in the 1940s. Some may recall the 6-foot-6 Connors as Lucas McCain from the TV western, “The Rifleman.”

Some who may have — but never did — played on the top level in both sports include these baseball Hall of Famers:

• Pitching great Bob Gibson averaged 22 points per game as a senior at Creighton University and played the 1957-58 season with the Harlem Globetrotters.

• Ferguson Jenkins, the first Canadian elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame, was a 6-foot-6 basketball star during high school in Ontario. Later he played the 1967 and 1968 seasons with the Globetrotters.

• Outfielder Dave Winfield, a 12-time, MLB All-Star, helped the University of Minnesota to the 1972 Big 10 basketball title. He was picked as a pitcher by the San Diego Padres fourth overall in the MLB draft and was drafted by both the NBA Atlanta Hawks and the ABA Utah Stars, along with the NFL’s Minnesota Vikings.