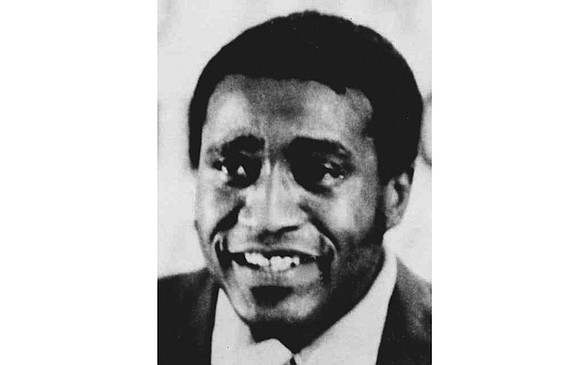

Cleo Hill to be inducted into collegiate hall of fame

Fred Jeter | 9/29/2017, 7:04 a.m.

The basketball life of the late Cleo Hill stands out for its dramatic rise, and also for its mysterious fall.

The Newark, N.J., native is remembered as being among the elite college players of his generation, albeit in the relative obscurity of Winston-Salem State University.

For his brilliance from 1957 to 1961 under Coach Clarence “Big House” Gaines, Hill will be inducted into the National Collegiate Basketball Hall of Fame on Nov. 19 in Kansas City, Mo.

The other reason Hill’s career merits careful study is how his promising NBA career abruptly faded, in part because of jealously by his teammates, but largely because of the color of his skin.

First some background on Hill at Winston-Salem State:

Essentially, he was Earl Monroe before Monroe.

The 6-foot-1 guard scored 2,488 points, leading the Rams to 1960 and 1961 CIAA championships. Hill was the best player in the CIAA and among the best nationally.

He was so good, in fact, the NBA St. Louis Hawks drafted Hill in the first round, and the eighth selection overall.

All systems were go until an October 1961, preseason game against Boston in Lexington, Ky. The teams were staying at the Phoenix Hotel.

Hill later referred to it as “the incident.”

Hours before the game, two famous Celtics players, Bill Russell and Sam Jones, both African-American, knocked on Hill’s hotel door. Russell and Jones had been denied service at the hotel restaurant and were proposing a boycott of the evening’s game.

Hill didn’t take the players’ word for it. He went to the restaurant to see for himself, and the bigoted results were the same.

The boycott was on.

Boston’s four African-American players — Russell, Jones, K.C. Jones and Tom Sanders — sat out the game, along with Hill and two other Hawks players who were African-American, Si Green and Woody Sauldsberry.

This infuriated Hawks’ owner Ben Kerner, and he never let go of the grudge.

Still, it was hard holding Hill back. He was that good. In his official NBA debut, he scored 26 points. It turned out to be the wrong thing to do.

St. Louis had won the NBA title in 1958 and was runner-up to Boston in 1959 and 1960. The Hawks had three white All-Star players — Bob Pettit, Cliff Hagan and Clyde Lovellette. They were in no mood to share star status with an African-American rookie from an obscure school.

“They never said anything to me,” Hill said is a 2010 ESPN documentary, “Black Magic.” “But they got paid for the points they scored. And here I was, taking their points.”

Kerner, the Hawks’ owner who sided with his established headliners, told Coach Paul Seymour to freeze Hill out. When Coach Seymour refused, he was fired at midseason.

Coach Seymour later said that Hill had been “white-balled.”

Hill’s playing time diminished and he finished with a scoring average of 5 points.

The next season, he was cut in training camp and no other team offered him a job. Hill suspects he was branded a malcontent by Kerner due to “the incident.”

Rarely has a first round draft choice faded so unceremoniously.

While Hill was at Winston-Salem State, the Rams secretly played pick-up games against an all-white squad from nearby Wake Forest University. At the time, Wake players included Billy Packer, who later became famous as a television commentator.

“Cleo could do it all,” Packer told ESPN. “I don’t think there is any doubt that if you took race out of the equation, and personality out of the equation, he would have been a major, major star in the NBA.”

__