Funeral traditions changed – maybe permanently – by COVID-19

Hazel Trice Edney and George Copeland Jr. | 5/6/2021, 6 p.m.

John E. Thomasson was a hero in his hometown. As a member of the Louisa County Board of Supervisors, he was the first African-American elected to public office in the county.

Across 98 years, he built a successful realty company, helped to save mortgages, paid for college scholarships and owned the local funeral home for 53 years, where he oversaw the burials of thousands of Virginians.

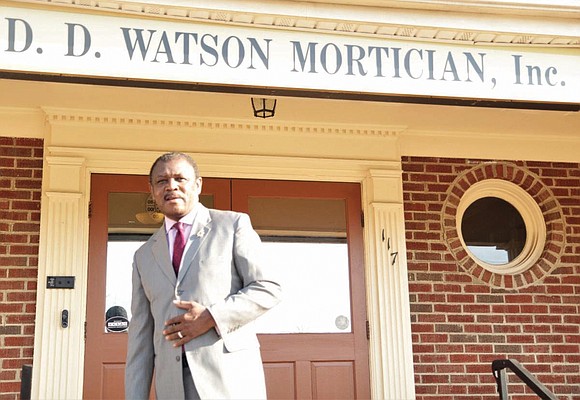

When he died of an age-related illness on July 22, there was hardly anyone in Louisa County who had not been touched by his life. Other than his wife of more than 65 years, the Rev. Christine Thomasson, there is likely no one who knows his impact better than his successor, D.D. Watson Jr., who was handpicked by Mr. Thomasson to purchase and take over his funeral home business in 2004.

And yet upon the death of Mr. Thomasson—a businessman, philanthropist, politician and public servant whose life and work was recognized this year in a proclamation from the Virginia Senate—the largest single gathering in his honor held barely 12 people. That’s because of government-imposed safety restrictions on public gatherings because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

“If it wasn’t for the COVID virus, he would have had a service fitting for a king,” Mr. Watson said in a recent interview with the Trice Edney News Wire. “His impact was so far-reaching, but his life could not be celebrated like I thought should have been fitting for him. COVID stole that.”

It hasn’t been just the homegoing celebrations for community figures like Mr. Thomasson that COVID-19 has impacted. During the past year, African-American funeral homes locally and nationally have been forced to adjust to handle the growing numbers of COVID-related deaths and the culture change COVID-19 has brought to African-American funeral traditions.

For Richard A. Lambert Sr., president and owner of Scott’s Funeral Home in Richmond, the last year has seen their funeral services double from their typical 16 to 18 per month. At the same time, they’ve had to greatly limit attendance at funerals, while adopting more tools that allow mourners to view and participate in funeral services offsite.

Similar changes have come to Mimms Funeral Home, according to president and director Mia Frances Mimms. The South Richmond funeral home has adopted remote viewing through internet streaming, another commonality among funeral homes during the year of COVID-19.

Mimms Funeral Home, which has its own crematory, also has been part of a growing reliance on cremations during the pandemic. According to the Cremation Association of North America, 58 percent of deaths nationally were handled by cremation during the first six months of the pandemic, a 3 percent increase from all of 2019.

Ms. Mimms did not have specifics on cremation numbers for the past year, but said the business has seen a general increase from years past. She also noted the emotional and psychological impact of the increased workload on employees.

“Sometimes we just have down time where we can all get together and just kind of voice what’s going on,” Ms. Mimms said. “It’s basically a judgment-free zone. I think that has helped all of us emotionally and mentally get through this, just to know that we’re all in it together.”

But as funeral homes work to maintain a necessary service during this time, new worries have emerged for those involved. More than a year since the coronavirus was declared a pandemic, Mr. Lambert, Mr. Watson and others see the pandemic-related changes in funeral traditions as long-term alterations.

“What concerns me is the loss of legacy ... because (families) are not able to have proper closure for the loved one and they’re left with additional grief,” Mr. Lambert said. “A lot of times people have said that they will have more of a service later, but as time goes on, people have a tendency to forget. Not everybody is given that proper closure.”

Mr. Watson echoed these concerns, speculating that COVID-related changes, such as Zoom goodbyes may “cause a nonchalant attitude about death.”

“A grandson who once would have made it home from California to be at grandpa’s funeral is now going to say, ‘Well, put it on Zoom. I can’t take off a day. Make it for 12 o’clock, which is 9 o’clock for me in California, and I’ll sit at my desk and watch the funeral.’ ” Mr. Watson said. “And so, it has made it unnecessary to come home to say your final goodbyes to grandpa who raised you, nurtured you and gave you the opportunity to go to college.”

There could be reasons for this change beyond nonchalance, according to Dr. Rahn K. Bailey, a forensics psychiatrist at the Charles Drew University School of Medicine in Los Angeles and the first Black physician to serve as head of psychiatry at Louisiana State University.

“I think that in a lot of ways, things have changed permanently. Fear drives behavior,” said Dr. Bailey, who predicts that five years from now, people will still not have gone back to their pre-COVID traditions. “I think there will not only be a continuing fear of COVID, but fear of any other possible illnesses that they don’t know.”

Those working in the mortuary field said they continue to respond to the changing demands of the pandemic as best they can, aided in part through their strong connections to the local community and to each other.

“This year has been very fast coming hasn’t it? Like every day, so different. We just did not know what to expect,” Ms. Mimms said. “And I do believe that the funeral homes in Richmond have all kind of come together through this.”

Even as funeral directors and morticians – the so-called “last responders” – work with bereaved families during the pandemic, many have suffered major losses of their own. More than 160 Black funeral directors and morticians have died from COVID-19, according to Rev. Hari P. Close II of Baltimore, president of the National Funeral Directors & Morticians Association Inc., which represents Black funeral directors.

“It’s an airborne virus. So, when you’re the embalmer, even when you’re wearing masks, that body has to be opened,” Rev. Close said. “The issue is, is the virus dead when the person dies? Or is it still alive? That’s why you have a lot of health examiners not trying to do autopsies because you’re opening up the remains making it more airborne.”

Despite the danger of infection, Rev. Close said that many states did not prioritize embalmers on the same level as first responders, rescue workers and doctors to receive personal protective equipment, which includes masks, sanitizer, gloves and protective clothing.

As millions of people across the United States have received vaccines and most states now are trending downward with COVID-19 deaths and hospitalizations, Rev. Close believes the Black community must do everything possible to guard against losing the tradition of holding large funeral gatherings.

“A lot of our families have expressed that they can’t wait to go back to tradition because we actually celebrate people’s lives and your friends and families are part of that celebration of comfort to get through it,” he said. “As I said to my colleagues in the industry, we cannot allow our culture to be changed, because once we let that segment dissolve of the celebration of life, we’re in trouble.”

“And I’ve expressed to some of my White counterparts how important this celebration is in the African-American community and the Hispanic community. We have a responsibility to the next generation to really emphasize the traditions of who we are.”