Working through long COVID

Months to years after being infected by the coronavirus, thousands in Virginia, including Delegate Delores L. McQuinn and U.S. Sen. Tim Kaine, push through lingering symptoms

George Copeland Jr. | 4/28/2022, 6 p.m.

Natarsha Eppes-Kelly has been working hard for the last four months to establish a new normal in her life.

A Dinwiddie resident and former mortgage specialist who now works as a beauty and skin care entrepreneur, Ms. Eppes-Kelly contracted COVID-19 in late August. Unable to be vaccinated at the time because of her diabetes, Ms. Eppes-Kelly initially focused on getting the rest of her family tested and taking stock of the potential impact.

The larger effects of her infection would quickly become clear in just a few days when she laid down but couldn’t seem to wake up. That lasted for four days.

Ms. Eppes-Kelly was rushed to a hospital by her husband when she proved unresponsive and was barely breathing. Her infection led to months of care in a Richmond hospital and later, at-home treatment, as the long-term effects of COVID-19 subsided and emerged again and again.

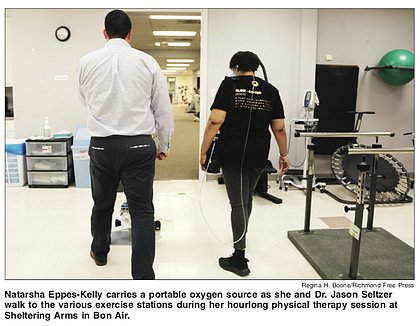

Now, nearly nine months after coming down with COVID-19, Ms. Eppes-Kelly is on the path to recovery at Sheltering Arms Physical Rehabilitation and Therapy Center in Bon Air, where she began rehab for her fatigue, diminished lung capacity and physical decline on New Year’s Day.

The experience can be taxing, with Ms. Eppes-Kelly taking regular breaks between activities and needing a portable oxygen machine to assist with breathing. But her determination to regain a measure of the health she has lost to COVID-19 is clear. And through the deep breaths she takes as she trains, she repeats a simple phrase: “I got this.”

“Mentally, I struggle every day. I break down at times. But I have to remember that I do this for a reason,” Ms. Eppes-Kelly said. “I feel like this was something that I had to go through. I’m very strong on faith and faith-driven, so I feel like this was my destiny.”

Ms. Eppes-Kelly is one of around 200 people with post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection, also known as “Long COVID,” being treated at Sheltering Arms, according to Dr. Jason Seltzer, a manager of therapy services who serves as her physical therapist.

On a larger scale, Ms. Eppes-Kelly is among 7.9 million to 23.9 million people in the United States who are grappling with the long-term effects of COVID-19. That’s about 10 percent to 30 percent of those who were infected with the virus.

In Virginia, an estimated 166,237 to 498,712 people are COVID long-haulers. Those great numbers are forcing a shift in how the medical community, including physicians, therapists and others, are dealing with the after-effects of COVID-19.

“I think we’re in a state of evolution,” said Dr. Seltzer, who noted how long COVID symptoms add difficulty when it comes to providing the best possible medical treatment for those affected.

“I think we’re learning that it’s not one-size-fits-all for treatment,” Dr. Seltzer said. “How I treat one patient is very different from how I treat the other. Diagnostics alone are not the only thing that can guide treatment and therapies. Interventions and management approaches need to be tailored.”

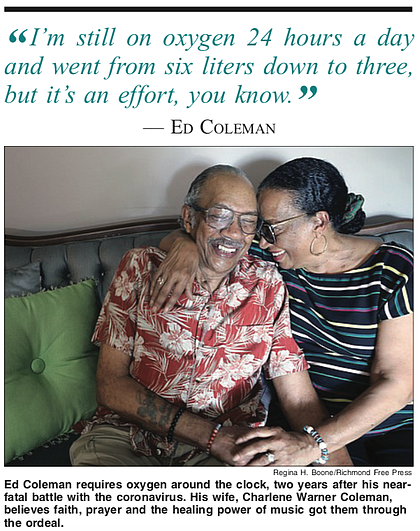

While Ms. Eppes-Kelly’s condition has caused a major change in her daily life, for Ed Coleman, long COVID is a hill he’s been working to climb since the pandemic started. Mr. Coleman first discovered his infection in early 2020 during a routine visit to McGuire Veterans Administration Medical Center in South Richmond. The virus led to severe health complications. He was even placed in a medically induced coma to help stabilize his blood pressure and other functions that were erratic under the effects of the virus.

He was 76 at the time and had a history of health issues. COVID-19 treatment was still nascent at the time and doctors weren’t positive about his prospects of making a recovery. Today, he continues to strive to improve as he gets acclimated to his new health status.

“I’m still in recovery,” Mr. Coleman told the Free Press in late March. “And I guess that’s going to go on for a little while longer.

“I’m still on oxygen 24 hours a day and went from six liters down to three, but it’s an effort, you know,” he said.

The initial impact of long COVID also had a mental toll for Mr. Coleman. He recognized the cognitive impairment from the virus, known as “brain fog,” even briefly forgetting during his recovery at home that he had lost a son in 2019.

Currently, Mr. Coleman continues to teach Shotokan karate as much as he can, and he regularly walks in his Chamberlayne Farms neighborhood to improve his health.

Ms. Eppes-Kelly also is working to adjust to the cognitive impact of her COVID-19 infection. It has forced her to re-learns parts of her new business and the work she previously put into it. Like Mr. Coleman, family support has been a major benefit for Ms. Eppes-Kelly. She said family members have stepped up to aid her entrepreneurial ambitions and home life and to help boost her physical and mental state.

“They have been such a big help,” Ms. Eppes-Kelly said. “It was a lot that was put on them and they answered the call.”

Ms. Eppes-Kelly’s and Mr. Coleman’s situations are a stark reminder of the high costs the virus presents for many, even months after initial infection and despite vaccines being widely available.

Delegate Delores L. McQuinn knows the situation all too well in both her professional and personal life. On March 14, she gathered with people at Virginia Union University for COVID-19 Remembrance Day, a day set aside by the Virginia General Assembly to remember the more than 20,000 Virginians who have lost their lives since the pandemic’s start. The resolution to make March 14 a day of remembrance each year was sponsored by Delegate McQuinn and approved during the 2021 legislative session.

The effects of COVID-19 have had a toll on Delegate McQuinn’s own family. Delegate McQuinn, her husband, Jonathan McQuinn, and their daughter, Daytriel McQuinn-Nzassi, continue to monitor and manage their long COVID symptoms, including shortness of breath, headaches and exhaustion. While Delegate McQuinn’s and her daughter’s symptoms are mild and sporadic, Mr. McQuinn’s moderate symptoms have left him with headaches, feeling exhausted and unexpected medical costs.

Delegate McQuinn has mixed feelings about the initial response of authorities to the spread of COVID-19 and its impact on communities of color. The trauma caused by COVID-19 continues to strike Black and brown communities, she said.

“We did some things right, but I also think that, in retrospect, there were some things that we could have done better, and not just Virginia but as a nation,” Delegate McQuinn said. “I’m hoping that we still understand that there are vulnerable communities. You still have to be careful. You have to be cautious of how communities are impacted.”

She believes more needs to be done to ensure a better quality of life for those affected long term by COVID-19 as well as for those who have lost friends and family to the virus. This will require more from those in positions of power to help, she said. No expense should be spared to correct and address the gap in care and research that has occurred so far in the pandemic.

“I know people are going to say, ‘Do you know what it’s going to cost?’ ” Delegate McQuinn said. “I don’t know the final cost, but I do know a lot of people have paid already for the negligence of those who should have and could have helped us to better understand this disease.

“We have a responsibility, and we have an obligation to do what we can to help those folks.”

The greater question now is how society can better understand and accommodate the long-term health consequences of COVID-19. Millions of people across the United States, including Ms. Eppes-Kelly, Mr. Coleman and the McQuinn family, are likely to be impacted by COVID-19 for years to come.

Dr. Seltzer stressed the need for long-term research into long COVID’s effects, as well as an expansion in understanding and awareness of symptoms to properly respond to the changes it will bring for individuals and groups.

“The more people who are aware of long COVID symptoms, the more health care providers who are seeking to address it, the faster we’ll get to a solution,” Dr. Seltzer said.

On the national level, U.S. Sen. Tim Kaine of Virginia introduced a bill in early March focused on improving the understanding of and response to long COVID, while accelerating research into the affliction.

Sen. Kaine’s own development of mild long COVID symptoms, which include a constant nerve tingling two years after becoming infected with the virus, was a major influence in his efforts to help people who live with long COVID. The bill, called the CARE for Long COVID Act, would raise public awareness of long COVID and treatment possibilities.

“We still just don’t know much about it,” Sen. Kaine said. “That’s why we need to do more research, put more information out there and then come up with treatments that work for people.”

Though his bill and a $10 billion COVID-19 spending bill have yet to be approved by Congress, Sen. Kaine seemed confident the legislation would find the support needed to pass.

“Employers also need to know how to accommodate employees with things like Zoom and telework and open up some opportunities for people that they might not have had before,” he said.

Dr. Seltzer believes the growing response to long COVID by the medical community will have a positive impact on treatment of those with the virus and other long-term afflictions.

“I’m happy to see that more and more long COVID clinics are popping up because that is a place where a patient with a single condition can go and be seen by specialists,” Dr. Seltzer said. “It sets a good example for how chronic conditions and diseases should be managed in the future.”

Ms. Eppes-Kelly urged people facing a future with long COVID to be steadfast in working to improve their health post infection, but not to overwhelm themselves in the effort.

“Take it day by day, hour by hour,” Ms. Eppes-Kelly said. “Just give yourself grace and just be patient.”